- Lowy Institute’s 2019 Asia Power Index puts Washington behind both Beijing and Tokyo for diplomatic influence

- Trump’s assault on trade has done little to stop Washington’s decline in regional influence, compared to Beijing, say experts

may be a dominant military force in Asia for now but short of going to war, it will be unable to stop its economic and diplomatic clout from declining relative to China’s power.

However, the institute also said China faced its own obstacles in the region, and that its ambitions would be constrained by a lack of trust from its neighbours.

has slapped tariffs on Chinese imports to reduce his country’s

. He most recently hiked a 10 per cent levy on US$200 billion worth of Chinese goods to 25 per cent and has also threatened to impose tariffs on other trading partners such as the European Union and Japan.

Herve Lemahieu, the director of the Lowy Institute’s Asian Power and Diplomacy programme, said: “The Trump administration’s focus on trade wars and balancing trade flows one country at a time has done little to reverse the relative decline of the United States, and carries significant collateral risk for third countries, including key allies of the United States.”

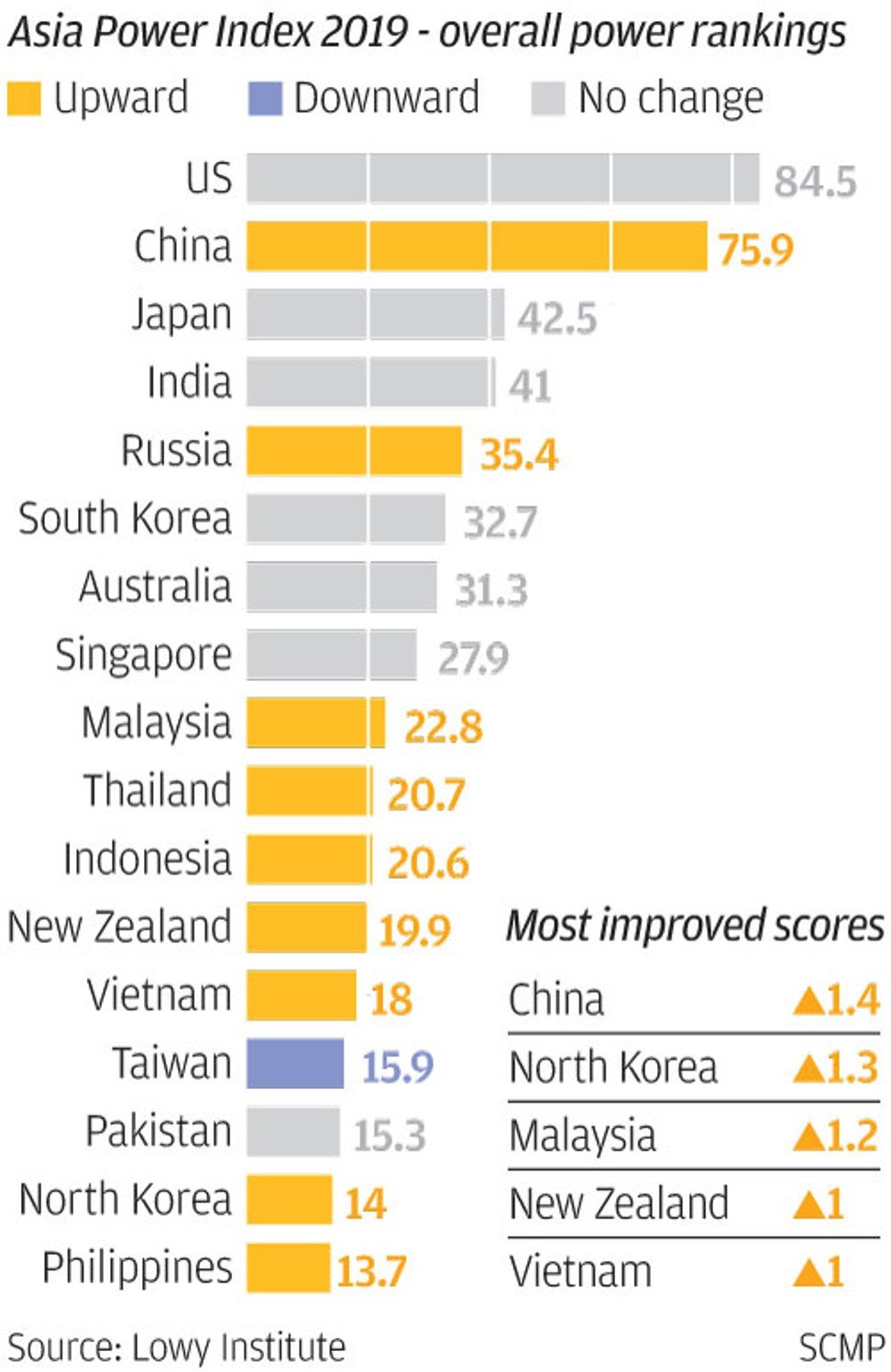

The index rates a nation’s power – which it defines as the ability to direct or influence choices of both state and non-state actors – using eight criteria. These include a country’s defence networks, economic relationships, future resources and military capability.

It ranked Washington behind both Beijing and Tokyo in terms of diplomatic influence in Asia, due in part to “contradictions” between its recent economic agenda and its traditional role of offering consensus-based leadership.

Toshihiro Nakayama, a fellow at the Wilson Centre in Washington, said the US had become its own enemy in terms of influence.

“I don’t see the US being overwhelmed by China in terms of sheer power,” said Nakayama. “It’s whether America is willing to maintain its internationalist outlook.”

But John Lee, a senior fellow at the Hudson Institute, said the Trump administration’s willingness to challenge the status quo on issues like trade could ultimately boost US standing in Asia.

“The current administration is disruptive but has earned respect for taking on difficult challenges which are of high regional concern but were largely ignored by the Obama administration –

illegal weapons and China’s predatory economic policies to name two,” said Lee.

“In midstream products such as smartphones and with regard to developing country markets, Chinese tech companies can still be competitive and profitable due to their economies of scale and price competitiveness,” said Jingdong Yuan, an associate professor at the China Studies Centre at the University of Sydney.

“However, to become a true superpower in the tech sector and dominate the global market remains a steep climb for China, and the Trump administration is making it all the more difficult.”

The future competitiveness of Beijing’s military, currently a distant second to Washington’s, will depend on long-term political will, according to the report, which noted that China already spends over 50 per cent more on defence than the 10

stands in the way of its primacy in Asia, according to the index, which noted Beijing’s unresolved territorial and historical disputes with 11 neighbouring countries and “growing degrees of opposition” to its signature

.

with a raft of countries including Vietnam, the Philippines and Brunei, and has been forced to renegotiate infrastructure projects in

and Myanmar due to concerns over feasibility and cost.

would persist and shape the global order into the distant future.

.

“This is important because Prime Minister Abe wants Japan to emerge as a constructive strategic player in the Indo-Pacific and high diplomatic standing is important to that end,” Lee said.

, ranked 14th, was the only place to record an overall decline in score, reflecting its waning diplomatic influence

during the past year.

COMMENTS: 3