Image copyright NATIONAL MUSEUM OF HEALTH AND MEDICINE

Image copyright NATIONAL MUSEUM OF HEALTH AND MEDICINEAll interest in living has ceased, Mahatma Gandhi, battling a vile flu in 1918, told a confidante at a retreat in the western Indian state of Gujarat.

The highly infectious Spanish flu had swept through the ashram in Gujarat where 48-year-old Gandhi was living, four years after he had returned from South Africa. He rested, stuck to a liquid diet during “this protracted and first long illness” of his life. When news of his illness spread, a local newspaper wrote: “Gandhi’s life does not belong to him – it belongs to India”.

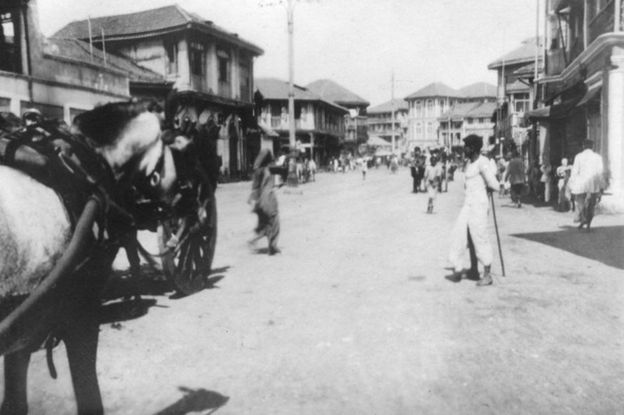

Outside, the deadly flu, which slunk in through a ship of returning soldiers that docked in Bombay (now Mumbai) in June 1918, ravaged India. The disease, according to health inspector JS Turner, came “like a thief in the night, its onset rapid and insidious”. A second wave of the epidemic began in September in southern India and spread along the coastline.

The influenza killed between 17 and 18 million Indians, more than all the casualties in World War One. India bore a considerable burden of death – it lost 6% of its people. More women – relatively undernourished, cooped up in unhygienic and ill-ventilated dwellings, and nursing the sick – died than men. The pandemic is believed to have infected a third of the world’s population and claimed between 50 and 100 million lives.

Gandhi and his febrile associates at the ashram were lucky to recover. In the parched countryside of northern India, the famous Hindi language writer and poet, Suryakant Tripathi, better known as Nirala, lost his wife and several members of his family to the flu. My family, he wrote, “disappeared in the blink of an eye”. He found the Ganges river “swollen with dead bodies”. Bodies piled up, and there wasn’t enough firewood to cremate them. To make matters worse, a failed monsoon led to a drought and famine-like conditions, leaving people underfed and weak, and pushed them into the cities, stoking the rapid spread of the disease.

Image copyright PRINT COLLECTOR

Image copyright PRINT COLLECTORTo be sure, the medical realities are vastly different now. Although there’s still no cure, scientists have mapped the genetic material of the coronavirus, and there’s the promise of anti-viral drugs, and a vaccine. The 1918 flu happened in the pre-antibiotic era, and there was simply not enough medical equipment to provide to the critically ill. Also western medicines weren’t widely accepted in India then and most people relied on indigenous medication.

Yet, there appear to be some striking similarities between the two pandemics, separated by a century. And possibly there are some relevant lessons to learn from the flu, and the bungled response to it.

The outbreak in Bombay, an overcrowded city, was the source of the infection’s spread back then – this something that virologists are fearing now. With more than 20 million people, Bombay is India’s most populous city and Maharashtra, the state where it’s located, has reported the highest number of coronivirus cases in the country.

By early July in 1918, 230 people were dying of the disease every day, up nearly three times from the end of June. “The chief symptoms are high temperature and pains in the back and the complaint lasts three days,” The Times of India reported, adding that “nearly every house in Bombay has some of its inmates down with fever”. Workers stayed away from offices and factories. More Indian adults and children were infected than resident Europeans. The newspapers advised people to not spend time outside and stay at home. “The main remedy,” wrote The Times of India, “is to go to bed and not worry”. People were reminded the disease spread “mainly through human contact by means of infected secretions from the nose and mouths”.

“To avoid an attack one should keep away from all places where there is overcrowding and consequent risk of infection such as fairs, festivals, theatres, schools, public lecture halls, cinemas, entertainment parties, crowded railway carriages etc,” wrote the paper. People were advised to sleep in the open rather than in badly ventilated rooms, have nourishing food and get exercise.

“Above all,” The Times of India added, “do not worry too much about the disease”.

Image copyright PRINT COLLECTOR

Image copyright PRINT COLLECTORColonial authorities differed over the source of infection. Health official Turner believed that the people on the docked ship had brought the fever to Bombay, but the government insisted that the crew had caught the flu in the city itself. “This had been the characteristic response of the authorities, to attribute any epidemic that they could not control to India and what was invariably termed the ‘insanitary condition’ of Indians,” observed medical historian Mridula Ramanna in her magisterial study of how Bombay coped with the pandemic.

Later a government report bemoaned the state of India’s government and the urgent need to expand and reform it. Newspapers complained that officials remained in the hills during the emergency, and that the government had thrown people “on the hands of providence”. Hospital sweepers in Bombay, according to Laura Spinney, author of Pale Rider: The Spanish Flu of 1918 and How It Changed the World, stayed away from British soldiers recovering from the flu. “The sweepers had memories of the British response to the plague outbreak which killed eight million Indians between 1886 and 1914.”

Image copyright PRINT COLLECTOR

Image copyright PRINT COLLECTOR“The colonial authorities also paid the price for the long indifference to indigenous health, since they were absolutely unequipped to deal with the disaster,” says Ms Spinney. “Also, there was a shortage of doctors as many were away on the war front.”

Eventually NGOs and volunteers joined the response. They set up dispensaries, removed corpses, arranged cremations, opened small hospitals, treated patients, raised money and ran centres to distribute clothes and medicine. Citizens formed anti-influenza committees. “Never before, perhaps, in the history of India, have the educated and more fortunately placed members of the community, come forward in large numbers to help their poorer brethren in time of distress,” a government report said.

Now, as the country battles another deadly infection, the government has responded swiftly. But, like a century ago, civilians will play a key role in limiting the virus’ spread. And as coronavirus cases climb, this is something India should keep in mind.

Source: The BBC