30/05/2020

- Embassy in France removes ‘false image’ on Twitter in latest online controversy amid accusations of spreading disinformation

- After months of aggressive anti-US posts by Chinese diplomats Beijing is cracking down on ‘smear campaigns’ at home

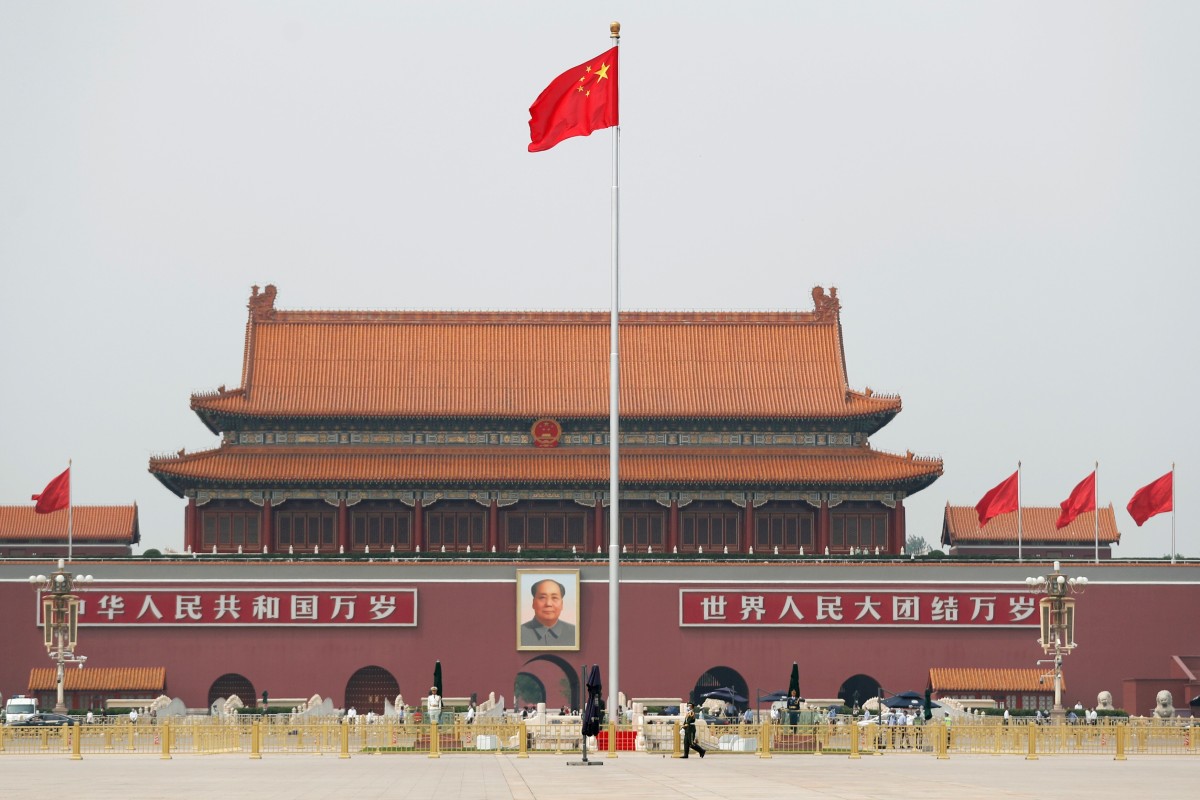

Beijing’s ‘Wolf Warrior’ diplomacy has coincided with a rise of nationalist content on Chinese social media. Photo: Reuters

Beijing is battling allegations that it is running a disinformation campaign on social media, as robust posts by its diplomats in Western countries promoting nationalist sentiment have escalated into a spat between China and other countries, especially the United States.

In the latest in a series of online controversies, the Chinese embassy in France claimed its official Twitter account had been hacked after it featured a cartoon depicting the US as Death, knocking on a door marked Hong Kong after leaving a trail of blood outside doors marked Iraq, Libya, Syria, Ukraine and Venezuela. The inclusion in the image of a Star of David on the scythe also prompted accusations of anti-Semitism.

Top China diplomats call for ‘Wolf Warrior’ army in foreign relations

25 May 2020

“Someone posted a false image on our official Twitter account by posting a cartoon entitled ‘Who is Next?’. The embassy would like to condemn it and always abides by the principles of truthfulness, objectivity and rationality of information,” it said on Monday.

The rise of China’s aggressive “Wolf Warrior” diplomacy has been regarded by analysts as primarily aimed at building support for the government at home but the latest incident is seen as an attempt by Beijing to take back control of the nationalist narrative it has unleashed.

Florian Schneider, director of the Leiden Asia Centre in the Netherlands, said the removal of the embassy’s tweet reflected a constant concern in Beijing about the range of people – including ordinary citizens – who were involved in spreading nationalistic material online.

“The state insists that its nationalism is ‘rational’, meaning it is meant to inspire domestic unity through patriotism but without impacting national interests or endangering social stability,” he said.

“This makes nationalism a mixed blessing for the authorities … if nationalist stories demonise the US or Japan or some other potential enemy, then any Chinese leader dealing diplomatically with those perceived enemies ends up looking weak.

“Trying to guide nationalist sentiment in ways that further the leadership’s interests is a difficult balancing act and I suspect this is partly the reason why the authorities are currently trying to clamp down on unauthorised, nationalist conspiracy theories.”

Too soon: Chinese advisers tell ‘Wolf Warrior’ diplomats to tone it down

The report came after months of social media posts – including by Chinese diplomats – defending China against accusations it had mishandled the coronavirus pandemic and attacking the US and other perceived enemies.

In March, Chinese foreign ministry spokesman Zhao Lijian promoted a conspiracy theory on Twitter suggesting the virus had originated in the US and was brought to China by the US Army. His comments were later downplayed, with China’s ambassador to the US Cui Tiankai saying questions about the origin of the virus should be answered by scientists.

Schneider said this showed that the state-backed nationalistic propaganda online was at risk of backfiring diplomatically.

“The authorities have to constantly worry that they might lose control of the nationalist narrative they unleashed, especially considering how many people produce content on the internet, how fast ideas spread, and how strongly commercial rationales drive misinformation online,” he said.

Last month, a series of widely shared social media articles about people in different countries “yearning to be part of China” resulted in a diplomatic backlash against Beijing. Kazakhstan’s foreign ministry summoned the Chinese ambassador in April to lodge a formal protest against the article.

Following the incident, the Cyberspace Administration of China, the country’s internet regulator which manages the “firewall” and censors material online, announced a two-month long “internet cleansing” to clear privately owned accounts which engage in “smear campaigns”.

A popular account named Zhidao Xuegong was shut down by the Chinese social media platform WeChat’s owner Tencent on Sunday after publishing an article which claimed Covid-19 may have killed 1 million people in the US and suggested the dead were “very likely” being processed as food.

The article had at least 100,000 readers, with 753 people donating money to support the account. According to Xigua Data, a firm that monitors traffic on Chinese social media, the account garnered more than 1.7 million page views for 17 articles in April.

According to a statement from WeChat, the account was closed for fabricating facts, stoking xenophobia and misleading the public.

A journalism professor at the University of Hong Kong said this case differed from the Chinese embassy’s tweet, despite both featuring anti-US sentiment.

Masato Kajimoto, who leads research on news literacy and the misinformation ecosystem, said the closure of the WeChat account seemed to be more about Chinese authorities feeling the need to regulate producers of media content whose motivations were often financial rather than political.

“I would think the government doesn’t like some random misinformation going wild and popular, which affects the overall storylines they would like to push, disseminate and control,” he said.

One way for China to respond to the situation was to fact-check social media and to position itself as a protector facts and defender of the integrity of public information, he said.

“In the age of social media, both fake news and fact-checking are being weaponised by people who try to influence or manipulate the narrative in one way or another,” Kajimoto said.

“Not only China but also many other authoritarian states in Asia are now fact-checking social media. Governments in Singapore, Thailand, Indonesia and other countries all do that.

“Such initiatives benefit them because they can decide what is true and what is not.”

Source: SCMP

Posted in abides, accusations, aggressive, allegations, anti-Semitism, anti-US posts, at home, ‘false image’, ‘smear campaigns’, ‘Who is Next?, ‘Wolf Warrior’ army, “internet cleansing”, “Wolf Warrior”, battles, battling, Beijing, campaign, cartoon, censors, China, Chinese ambassador, Chinese diplomats, chinese foreign ministry spokesman, Chinese social media, coincided, condemn it, conspiracy theories, control, controversy, coronavirus outbreak, Coronavirus pandemic, cracking down, Death, diplomacy, disinformation, door, doors, embassy, European Union, firewall, foreign relations, France, Hong Kong, Indonesia, information, Iraq, Kazakhstan’s foreign ministry, knocking, leaving, Leiden Asia Centre, Libya, marked, narrative, nationalist, nationalist content, objectivity, online, principles, prompted, rationality, removes, running, scythe, Singapore, social media, spreading, Star of David, Syria, TENCENT, Thailand, the Netherlands, trail of blood, truthfulness, Twitter, Ukraine, Uncategorized, United States, University of Hong Kong, Venezuela, weaponised, WeChat’s, xenophobia, Xigua Data |

Leave a Comment »

01/04/2020

- The coronavirus has fuelled explosive growth of the app, which now has 800 million users, few of whom will know it is owned by China’s ByteDance

- While videos of dancing teens may seem benign, there are growing fears in America it could be a Trojan Horse for mass surveillance by Beijing

TikTok is seen by some as the latest front in the US-China tech war. Photo: Shutterstock

Y

our average, not-so-hip adult would have probably drawn a blank at the mention of

not long ago – unless they have a child addicted to the wildly popular app, on which users make and share short, amusing videos.

It has grown explosively since its 2016 launch, with 800 million monthly active users now – 300 million of them outside China in places such as India (120 million) and the

(37 million). And many have no idea it is owned by a Chinese company, ByteDance.

The first Chinese app to mount a real global challenge to Facebook and Instagram, it is seen as one of the shiniest new weapons in the US-China technology war. And a boost, perhaps, to Chinese soft power.

TikTok, the missing link between Hong Kong and Indian protesters?

9 Feb 2020

It experienced a growth spurt in 2019 that analysts predicted would slow a little this year. That, however, was before the

coronavirus, which seems to be giving the app a bump, especially beyond its core teenage fan base.

As pandemic fears rise and millions are stuck indoors, major Hollywood celebrities such as Jennifer Lopez, 50, have taken to posting their own all-singing, all-dancing videos, which then go viral on other media platforms.

Even the

World Health Organisation has jumped on the bandwagon, joining the app in late February to share public health advice.

The TikTok logo on a smartphone. Photo: Getty Images

But to some, the growth of TikTok is far from benign.

Privacy advocates and several US congressmen want to rein in the app over concerns it may censor and monitor content for the Chinese government, and be used for misinformation and election interference. This despite the fact that TikTok keeps its servers outside China and swears it will not hand over user data.

Are these fears justified – or fuelled by political and anticompetitive motives?

Thinkers such as Yuval Noah Harari warn that the

coronavirus pandemic could be a watershed in the history of mass surveillance.

But Eric Harwit, a professor of Asian studies at the University of Hawaii, does not buy such arguments against TikTok, especially given that 60 per cent of its US users are aged 16 to 24.

“ByteDance has done a pretty good job of having a firewall between TikTok and the Chinese version of it, Douyin.

TikTok, iPhone: all you need to escape Mumbai’s slums – for 15 seconds

“Also, many users in the US are teens and they’re not a particularly useful source of national security information.

“So I’d say the concerns are motivated more by a general fear of any kind of Chinese telecommunication application rather than actual attempts to siphon off valuable US intelligence information.

“And Facebook and other American companies have similar products,” Harwit points out. “US government officials will always want to protect American commercial interests.”

Sarah Cook, a China analyst for Freedom House – the US government-funded think tank – disagrees.

“We have concerns about how Facebook and Twitter deal with information affecting electoral politics, and that’s magnified if you’re talking about a Chinese company that now has a user base that rivals theirs.”

Chinese officials, she argues, have shown a willingness to censor and manipulate information well beyond their country’s borders – for instance, regarding the scale of the initial outbreak in Wuhan, an obfuscation that may have exacerbated its impact abroad.

“For those who think Chinese government censorship is only Chinese people’s problem, this pandemic shows how much that’s not the case.

“And even if it’s not happening right now with TikTok, the concern is that Chinese companies are beholden to their government, whether they want to be or not.

“I’m not saying block TikTok entirely,” she says. “It’s a question of looking at it in a democratic system and deciding on reasonable oversight and safeguards to protect users and information flows when that time comes.”

When it comes to expanding China’s cultural influence, though, neither Cook nor Harwit believes the app is especially effective.

Most people are oblivious to its Chinese origins, which the user experience does not reflect in any way. So there is no goodwill-generating soft power of the sort wielded by, say,

through the K-pop industry.

If anything, TikTok often promotes the increasingly homogenous, Western-leaning culture seen on many globally popular social media apps.

So says Morten Bay, a lecturer in digital and social media at the University of Southern California’s Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism.

“A semi-Western culture, with small variations of local culture, is becoming the norm on social media. And Chinese soft power is difficult to assert because there’s no value difference.”

And even if Chinese tech companies keep taking bigger bites of the Western market, he is sceptical of China’s “ability to leverage that for soft power in a geopolitical sense”.

“Because there is a very big apparatus pushing against China in that regard. As soon as TikTok started gaining traction in the US, people came out against it, trying to make everyone aware of the privacy and geopolitical issues.

The #KaunsiBadiBaatHai campaign on TikTok aims to raise awareness about women’s safety issues in India. Image: TikTok

“So China faces a lot of resistance,” Bay concludes. “And I’m not sure a social media platform on its own can do much about that.”

Still, if you had to back a horse in this race, TikTok would be it, says Zhang Mengmeng.

When she and her colleagues from global industry analysis firm Counterpoint Research visited the company, they were impressed by its research and development capabilities.

“Because they’re a very young company, their pace for incubating new projects is a lot faster, especially compared to successful but older internet companies in China which have been around for 15 to 20 years.

Indian invasion of Chinese social media apps sparks fear and loathing in New Delhi

“They have lots of little start-up projects within the company and their organisational structure is very flat – it doesn’t matter what your age is, if you have a good idea, you get promoted very quickly.”

TikTok’s rise is also emblematic of a broader role reversal in the US-China tech war, she believes.

“Before, the US was more advanced in terms of internet development and China seemed to just copy its new ideas. Now, this is reversing. There are so many people in China using the internet that start-ups there can test ideas very easily.

“So now it seems like a lot of US companies are trying to see what ideas are coming out of China.” ■

Source: SCMP

Posted in addicted, Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism, APP, bandwagon, Beijing, benign, Bytedance, censorship, China, Chinese, chinese government, coronavirus, Coronavirus pandemic, Culture, explosive growth, Facebook, firewall, fuelled, geopolitical issues, homogenous, Hong Kong, India, Indian, industry, Instagram, intelligence information, IPhone, Jennifer Lopez, jumped, K-pop, living rooms, mass surveillance, Mumbai's, pandemic, protesters, public health advice, semi-Western culture, siphon off, slums, soft power, South Korea, telecommunication application, TikTok, time bomb, Trojan Horse, Twitter, Uncategorized, United States, University of Hawaii, University of Southern California’s, US-China technology war, watershed, women's safety issues, World Health Organisation, Wuhan |

Leave a Comment »