Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGESIt took China less than 70 years to emerge from isolation and become one of the world’s greatest economic powers.

As the country celebrates the anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China, we look back on how its transformation spread unprecedented wealth – and deepened inequality – across the Asian giant.

“When the Communist Party came into control of China it was very, very poor,” says DBS chief China economist Chris Leung.

“There were no trading partners, no diplomatic relationships, they were relying on self-sufficiency.”

Over the past 40 years, China has introduced a series of landmark market reforms to open up trade routes and investment flows, ultimately pulling hundreds of millions of people out of poverty.

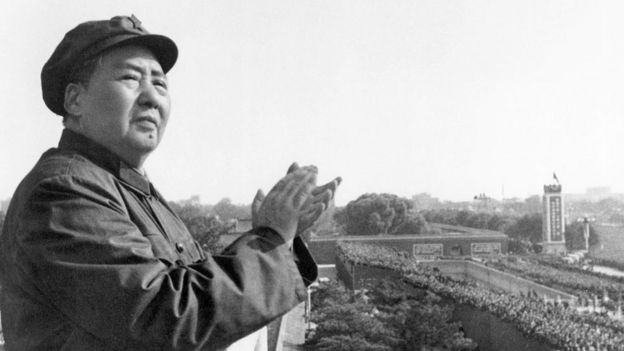

The 1950s had seen one of the biggest human disasters of the 20th Century. The Great Leap Forward was Mao Zedong’s attempt to rapidly industrialise China’s peasant economy, but it failed and 10-40 million people died between 1959-1961 – the most costly famine in human history.

This was followed by the economic disruption of the Cultural Revolution in the 1960s, a campaign which Mao launched to rid the Communist party of his rivals, but which ended up destroying much of the country’s social fabric.

‘Workshop of the world’

Yet after Mao’s death in 1976, reforms spearheaded by Deng Xiaoping began to reshape the economy. Peasants were granted rights to farm their own plots, improving living standards and easing food shortages.

The door was opened to foreign investment as the US and China re-established diplomatic ties in 1979. Eager to take advantage of cheap labour and low rent costs, money poured in.

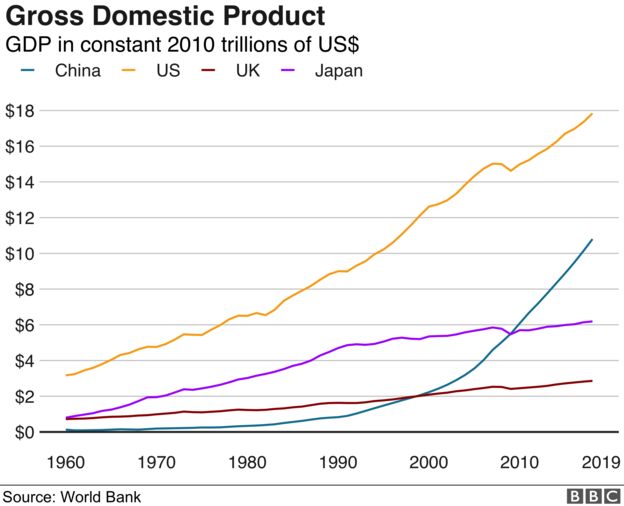

“From the end of the 1970s onwards we’ve seen what is easily the most impressive economic miracle of any economy in history,” says David Mann, global chief economist at Standard Chartered Bank.

Through the 1990s, China began to clock rapid growth rates and joining the World Trade Organization in 2001 gave it another jolt. Trade barriers and tariffs with other countries were lowered and soon Chinese goods were everywhere.

“It became the workshop of the world,” Mr Mann says.

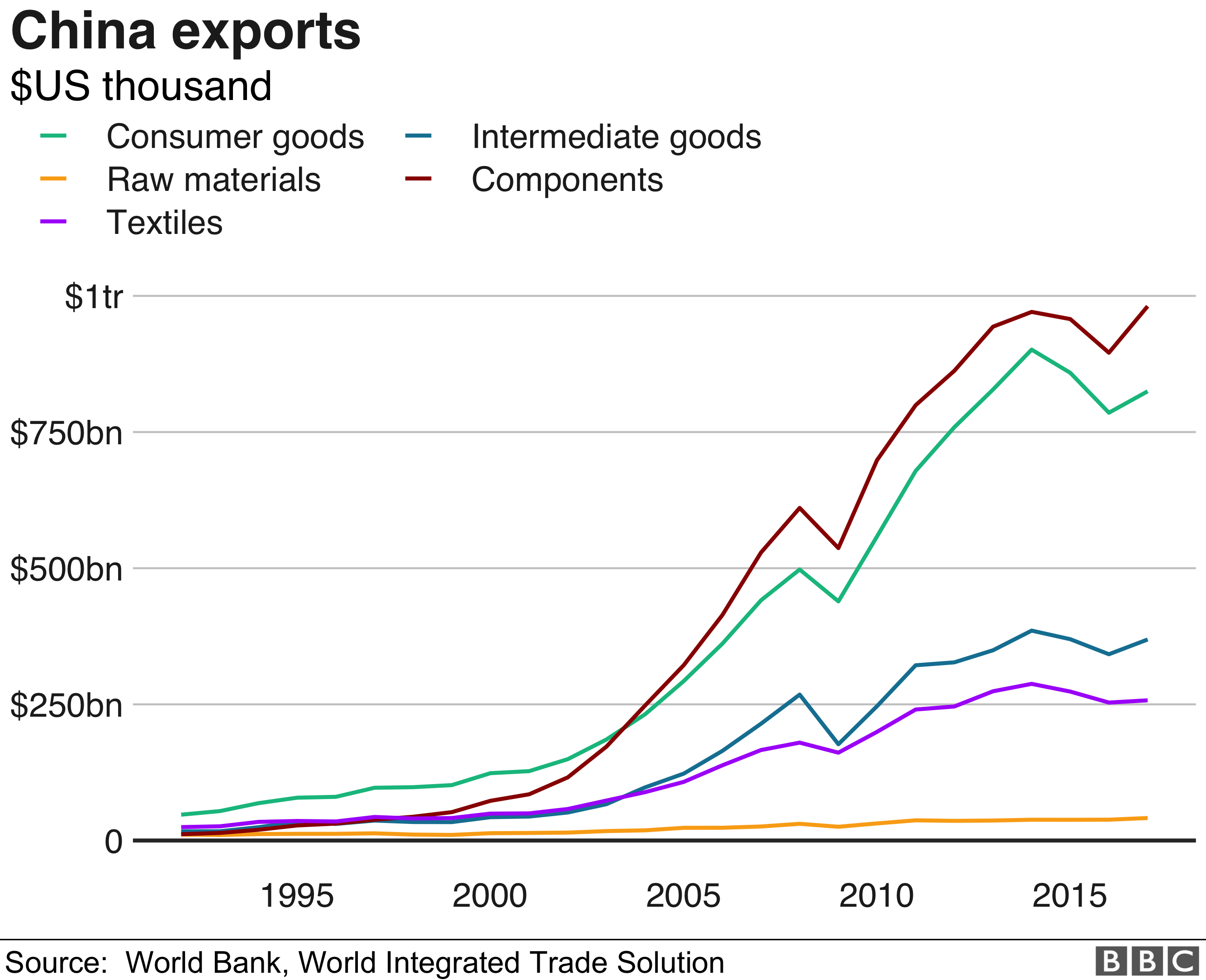

Take these figures from the London School of Economics: in 1978, exports were $10bn (£8.1bn), less than 1% of world trade.

By 1985, they hit $25bn and a little under two decades later exports valued $4.3trn, making China the world’s largest trading nation in goods.

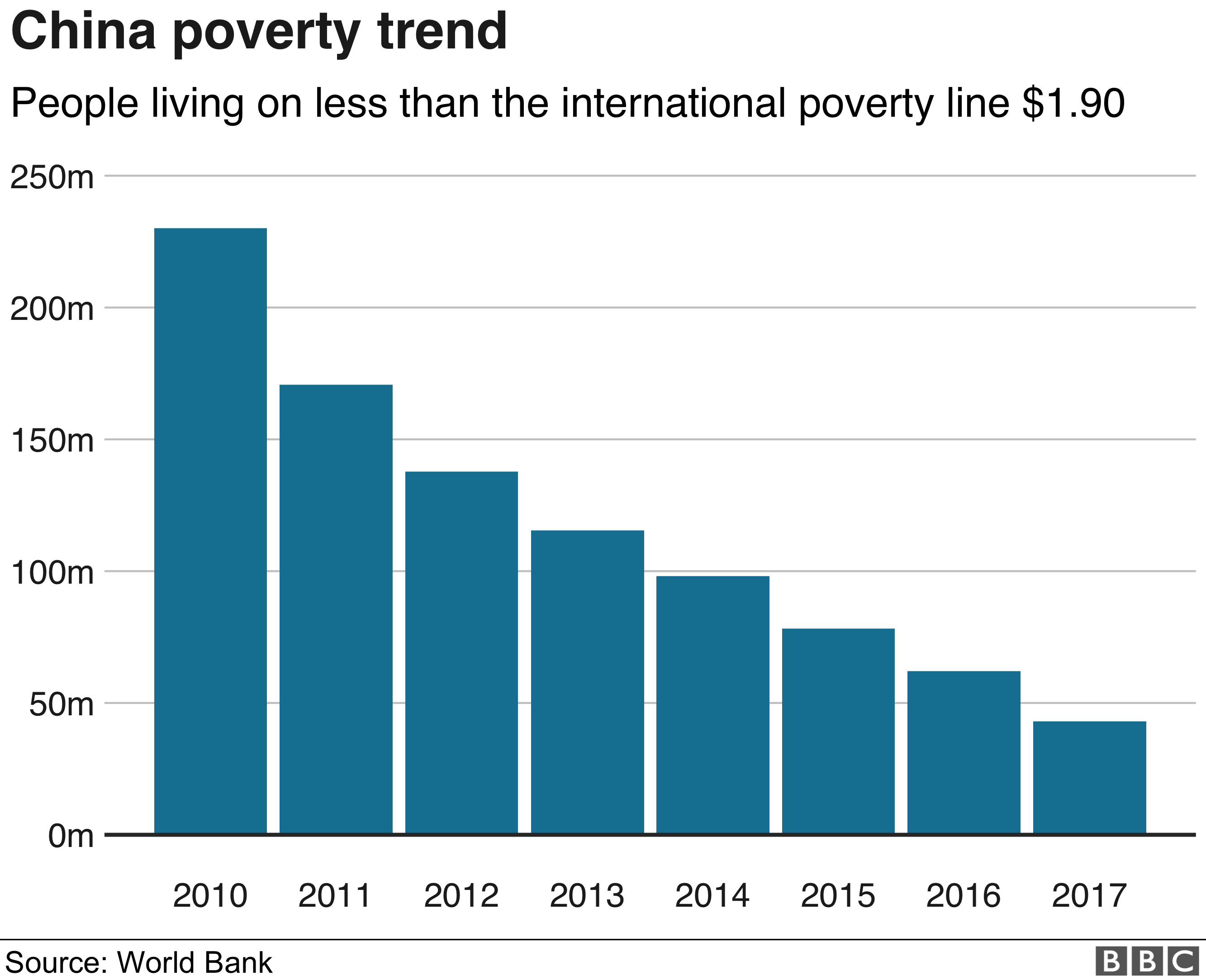

Poverty rates tumble

The economic reforms improved the fortunes of hundreds of millions of Chinese people.

The World Bank says more than 850 million people been lifted out of poverty, and the country is on track to eliminate absolute poverty by 2020.

At the same time, education rates have surged. Standard Chartered projects that by 2030, around 27% of China’s workforce will have a university education – that’s about the same as Germany today.

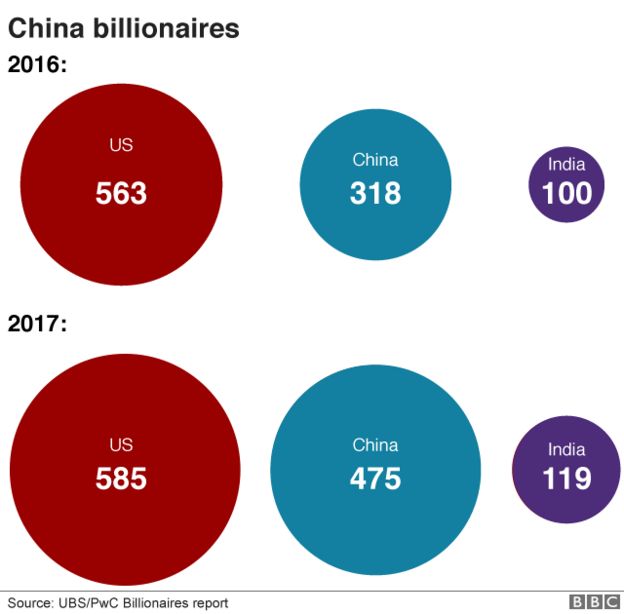

Rising inequality

Still, the fruits of economic success haven’t spread evenly across China’s population of 1.3 billion people.

Examples of extreme wealth and a rising middle class exist alongside poor rural communities, and a low skilled, ageing workforce. Inequality has deepened, largely along rural and urban divides.

“The entire economy is not advanced, there’s huge divergences between the different parts,” Mr Mann says.

The World Bank says China’s income per person is still that of a developing country, and less than one quarter of the average of advanced economies.

China’s average annual income is nearly $10,000, according to DBS, compared to around $62,000 in the US.

Slower growth

Now, China is shifting to an era of slower growth.

For years it has pushed to wean its dependence off exports and toward consumption-led growth. New challenges have emerged including softer global demand for its goods and a long-running trade war with the US. The pressures of demographic shifts and an ageing population also cloud the country’s economic outlook.

Still, even if the rate of growth in China eases to between 5% and 6%, the country will still be the most powerful engine of world economic growth.

“At that pace China will still be 35% of global growth, which is the biggest single contributor of any country, three times more important to global growth than the US,” Mr Mann says.

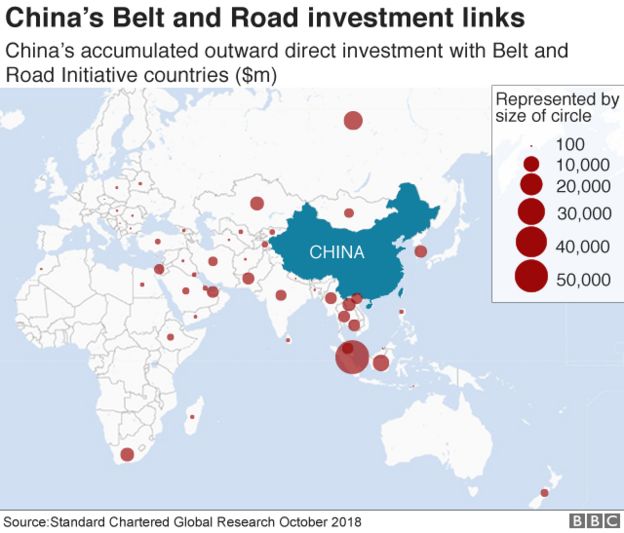

The next economic frontier

China is also carving out a new front in global economic development. The country’s next chapter in nation-building is unfolding through a wave of funding in the massive global infrastructure project, the Belt and Road Initiative.

The so-called new Silk Road aims to connect almost half the world’s populations and one-fifth of global GDP, setting up trade and investment links that stretch across the world.

Source: The BBC