Image copyrightREUTERS

Image copyrightREUTERSWhatsApp, India’s most popular messaging platform, has become a vehicle for misinformation and propaganda ahead of the upcoming election. The Facebook-owned app has announced new measures to fight this but experts say the scale of the problem is overwhelming.

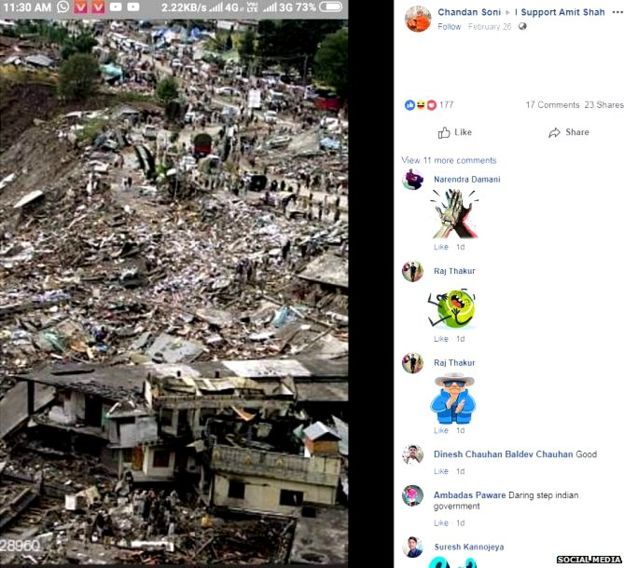

India was in the grip of patriotic fervour in early March when WhatsApp groups were flooded with photographs claiming to show proof that unprecedented Indian air strikes in Pakistani territory had been successful.

While India’s government said the 26 February strikes had killed a “large number of militants”, Islamabad insisted there had been no casualties.

But BBC fact-checkers found that the photos – purportedly of dead militants and a destroyed training camp – were old images that were being shared with false captions.

One photo showed a crowd of Muslim women and men gathered around three bodies but those pictured were actually victims of a suicide attack in Pakistan in 2014. A series of photos – of crumbling buildings, piles of debris and bodies in shrouds lying on the ground – were traced to a devastating earthquake in Pakistan-administered Kashmir in 2005.

Image copyrightFACEBOOK

Image copyrightFACEBOOK WhatsApp and Facebook have been struggling to curb the impact of “fake news” – messages, photos and videos peddling misleading or outright false information – in elections around the world.

WhatsApp and Facebook have been struggling to curb the impact of “fake news” – messages, photos and videos peddling misleading or outright false information – in elections around the world.But India’s upcoming election – the world’s largest democratic exercise – is seen as a significant test. Internet usage in rural areas has exploded since the last election in 2014, fuelled by the world’s lowest mobile data prices.

In the lead-up to the vote, Facebook has removed hundreds of accounts and pages for misleading users. WhatsApp, meanwhile, has launched a service to verify reports sent in by users and to study the scale of misinformation on the platform.

What’s the scale of the problem?

India poses a particularly complex problem for Facebook. It is WhatsApp’s largest market – more than 200 million Indians use the app – and a place where users forward more content than anywhere else in the world.

The fact that up to 256 people can be part of a group chat makes it incredibly popular with extended families and large groups of friends. While much of these daily conversations involve people making plans, sharing jokes and catching up – political messages and videos are also shared widely.

BBC research last year found that a rising tide of nationalism was driving Indians to share fake news. Participants tended to assume that WhatsApp messages from family and friends could be trusted and sent on without any checks.

Prasanto K Roy, a tech writer, is in a group of more than 100 classmates from his old high school in Delhi. There are Christians, Hindus and Muslims in the group.

“Since 2014, we have been seeing a great deal of polarisation,” he said. “About 10 people are incessantly sending out fake stuff. Some people like me are doing fact checks and telling them but we are being ignored.”

- Is Facebook winning the fake news war?

- ‘Mum’s WhatsApps are crashing my phone’

- Why India has world’s cheapest mobile data

Many Indians were first introduced to the internet through their smartphones. A recent Reuters Institute survey of English-language Indian internet users found that 52% of respondents got news via WhatsApp. The same proportion said they got their news from Facebook.

But content shared via WhatsApp has led to murder. At least 31 people were killed in 2017 and 2018 as a result of mob attacks fuelled by rumours on WhatsApp and social media, a BBC analysis found.

What’s happening before the election?

Both of the main parties – the governing Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) of Prime Minister Narendra Modi and the opposition Congress – are exploiting the power of WhatsApp to try to influence India’s 900 million eligible voters.

Before the campaign began, the BJP had plans to assign some 900,000 people with the specific task of localised WhatsApp campaigning, the Hindustan Times newspaper reported.

Congress, the party of the Nehru-Gandhi political dynasty, is focusing on uploading campaign content on Facebook and distributing it via WhatsApp.

Both parties have been accused of spreading false or misleading information, or misrepresentation online. On 1 April, Facebook removed 687 pages or accounts that it said were linked to the Congress party for “co-ordinated inauthentic behaviour”.

Pro-BJP Facebook pages – possibly as many as 200 – were also taken down, according to reports, although Facebook did not confirm this. (The social media company did not respond to a request for an explanation).

The BJP began setting up WhatsApp groups en masse around 2016 as it saw an opportunity to reach vast numbers of people, said Shivam Shankar Singh, a former BJP data analyst who worked on regional elections in 2017 and 2018.

By mapping names on electoral rolls against purchased phone numbers and names, it was able to create groups based on certain demographics – such as caste or religion – and target messaging, he said.

Mr Singh, who now works for anti-BJP opposition parties in the state of Bihar, estimated that there were at least 20,000 pro-BJP WhatsApp groups in northern Uttar Pradesh, India’s most populous state.

National party spokesman Gopal Krishna Agarwal denied that the party had any official policy to set up WhatsApp groups – other than to facilitate communication between party workers.

He said supporters and members at a local level were allowed to set up groups, but that these had no official link to the party.

“We don’t want to control it, it’s an open social media platform,” he said.

Why does WhatsApp pose a unique problem?

Indian fact-checking websites like AltNews and Boom frequently debunk political posts shared on Facebook and Twitter – such as reports that a British analyst of Indian elections had called Congress leader Rahul Gandhi “stupid” or that an air force pilot seen as a national hero had joined Congress.

These posts, while not promoted by official party accounts, are often spread widely by unofficial groups or people supporting the parties. They are then sometimes shared by politicians.

- On the frontline of India’s WhatsApp fake news war

- The Indian policewoman who stopped WhatsApp mob killings

“Facebook and Twitter are platforms that do not allow too much secrecy which allows fact-checkers like us to trace who the bad actors are in many of the cases,” said Jency Jacob, the founder of Indian fact-checking site Boom.

The difference with WhatsApp is that posts there are private and protected by encryption. Mr Roy likened it to “something of a black hole”.

“No-one, including WhatsApp itself, gets to see, read, filter or analyse text messages,” he said.

This is unlikely to change – the company said it “deeply believes in people’s ability to communicate privately online”.

What has the company done?

Amid the furore over mob lynchings last year, WhatsApp limited the number of times a user can forward a message to five. It also now labels forwarded messages.

The company has launched a nationwide advertising campaign in 10 languages, which it says has reached hundreds of millions of Indians. It also says that it bans two million accounts globally every month that are sending automated spam messages.

Image copyrightREUTERS

Image copyrightREUTERSNew privacy settings also allow users to decide who can add them to groups. Previously any WhatsApp user could be added to a group by any other. Now you can choose to only be added automatically to groups by contacts, or by no-one at all.

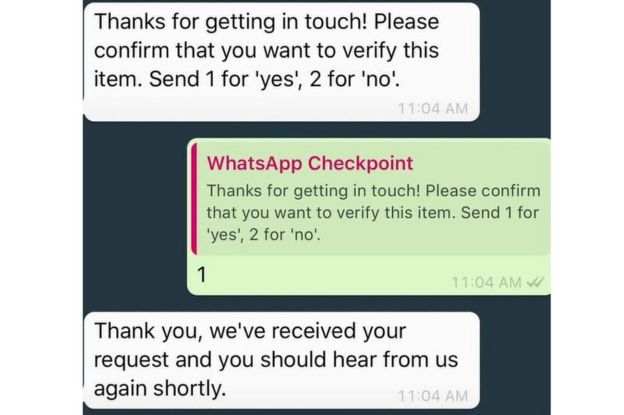

On 2 April the company announced a new project – Checkpoint – that allows users to send in suspicious messages in English and four Indian languages to WhatsApp for verification. Users are told if the message is true, false, misleading or disputed.

It was reported widely as a new fact-checking service but the company has since emphasised that it mostly aims to “study the misinformation phenomenon” and that not all users will receive a response.

Is it working?

While WhatsApp said its moves had decreased forwarded messages by 25%, fact-checkers at other organisations say fake news is still rampant. And they are frustrated that the same rumours and conspiracy theories that they have already debunked – that the Nehru-Gandhi political dynasty have Muslim roots, for example – keep resurfacing.

They say that unless WhatsApp changes its stance on encryption and privacy, the introduction of features similar to those that exist on Facebook – for example, flagging debunked content to users who try to forward it – is impossible.

“The BJP is the only party that has WhatsApp groups at this scale,” Mr Singh said. “The other parties can’t do it now because WhatsApp has changed its policies.”

Source: The BBC