Image copyright GETTY IMAGES

Image copyright GETTY IMAGESWhen I spoke to him on the phone, he had just returned home to his village in the northern state of Rajasthan from neighbouring Gujarat, where he worked as a mason.

In the rising heat, Goutam Lal Meena had walked on macadam in his sandals. He said he had survived on water and biscuits.

In Gujarat, Mr Meena earned up to 400 rupees ($5.34; £4.29) a day and sent most of his earnings home. Work and wages dried up after India declared a 21-day lockdown with four hours notice on the midnight of 24 March to prevent the spread of coronavirus. (India has reported more than 1,000 Covid-19 cases and 27 deaths so far.) The shutting down of all transport meant that he was forced to travel on foot.

“I walked through the day and I walked through the night. What option did I have? I had little money and almost no food,” Mr Meena told me, his voice raspy and strained.

He was not alone. All over India, millions of migrant workers are fleeing its shuttered cities and trekking home to their villages.

These informal workers are the backbone of the big city economy, constructing houses, cooking food, serving in eateries, delivering takeaways, cutting hair in salons, making automobiles, plumbing toilets and delivering newspapers, among other things. Escaping poverty in their villages, most of the estimated 100 million of them live in squalid housing in congested urban ghettos and aspire for upward mobility.

Image copyright GETTY IMAGES

Image copyright GETTY IMAGESLast week’s lockdown turned them into refugees overnight. Their workplaces were shut, and most employees and contractors who paid them vanished.

Sprawled together, men, women and children began their journeys at all hours of the day last week. They carried their paltry belongings – usually food, water and clothes – in cheap rexine and cloth bags. The young men carried tatty backpacks. When the children were too tired to walk, their parents carried them on their shoulders.

They walked under the sun and they walked under the stars. Most said they had run out of money and were afraid they would starve. “India is walking home,” headlined The Indian Express newspaper.

The staggering exodus was reminiscent of the flight of refugees during the bloody partition in 1947. Millions of bedraggled refugees had then trekked to east and west Pakistan, in a migration that displaced 15 million people.

Image copyright GETTY IMAGES

Image copyright GETTY IMAGESThis time, hundreds of thousands of migrant workers are desperately trying to return home in their own country. Battling hunger and fatigue, they are bound by a collective will to somehow get back to where they belong. Home in the village ensures food and the comfort of the family, they say.

Clearly, a lockdown to stave off a pandemic is turning into a humanitarian crisis.

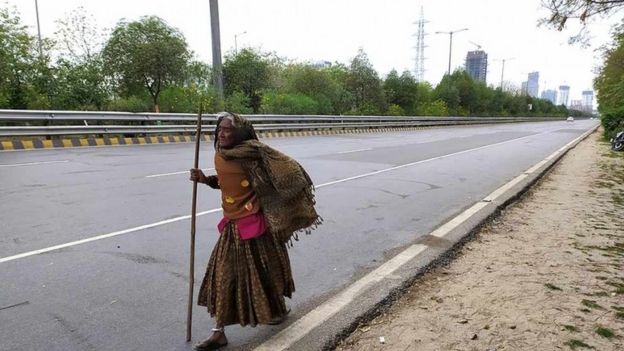

Among the teeming refugees of the lockdown was a 90-year-old woman, whose family sold cheap toys at traffic lights in a suburb outside Delhi.

Kajodi was walking with her family to their native Rajasthan, some 100km (62 miles) away. They were eating biscuits and smoking beedis, – traditional hand-rolled cigarettes – to kill hunger. Leaning on a stick, she had been walking for three hours when journalist Salik Ahmed met her. The humiliating flight from the city had not robbed her off her pride. “She said she would have bought a ticket to go home if transport was available,” Mr Ahmed told me.

- What India can learn from 1918 flu to fight Covid-19

- India gambles on lockdown to save millions

- Coronavirus: Why is India testing so little?

Others on the road included a five-year-old boy who was on a 700km (434 miles) journey by foot with his father, a construction worker, from Delhi to their home in Madhya Pradesh state in central India. “When the sun sets we will stop and sleep,” the father told journalist Barkha Dutt. Another woman walked with her husband and two-and-a-half year old daughter, her bag stuffed with food, clothes and water. “We had a place to stay but no money to buy food,” she said.

Then there was Rajneesh, a 26-year-old automobile worker who walking 250km (155 miles) to his village in neighbouring Uttar Pradesh. It would take him four days, he reckoned. “We will die walking before coronavirus hits us,” the man told Ms Dutt.

He was not exaggerating. Last week, a 39-year-old man on a 300km (186 miles) trek from Delhi to Madhya Pradesh complained of chest pain and exhaustion and died; and a 62-year-old man, returning from a hospital by foot in Gujarat, collapsed outside his house and died. Four other migrants, turned away at the borders on their way to Rajasthan from Gujarat, were mowed down by a truck on a dark highway.

As the crisis worsened, state governments scrambled to arrange transport, shelter and food.

Image copyright SALIK AHMED/OUTLOOK

Image copyright SALIK AHMED/OUTLOOKBut trying to transport them to their villages quickly turned into another nightmare. Hundreds of thousands of workers were pressed against each other at a major bus terminal in Delhi as buses rolled in to pick them up.

Delhi chief minister Arvind Kejriwal implored the workers not to leave the capital. He asked them to “stay wherever you are, because in large gatherings, you are also at risk of being infected with the coronavirus.” He said his government would pay their rent, and announced the opening of 568 food distribution centres in the capital. Prime Minister Narendra Modi apologised for the lockdown “which has caused difficulties in your lives, especially the poor people”, adding these “tough measures were needed to win this battle.”

Whatever the reason, Mr Modi and state governments appeared to have bungled in not anticipating this exodus.

Mr Modi has been extremely responsive to the plight of Indian migrant workers stranded abroad: hundreds of them have been brought back home in special flights. But the plight of workers at home struck a jarring note.

“Wanting to go home in a crisis is natural. If Indian students, tourists, pilgrims stranded overseas want to return, so do labourers in big cities. They want to go home to their villages. We can’t be sending planes to bring home one lot, but leave the other to walk back home,” tweeted Shekhar Gupta, founder and editor of The Print.

Image copyright GETTY IMAGES

Image copyright GETTY IMAGESThe city, says Chinmay Tumbe, author of India Moving: A History of Migration, offers economic security to the poor migrant, but their social security lies in their villages, where they have assured food and accommodation. “With work coming to a halt and jobs gone, they are now looking for social security and trying to return home,” he told me.

Also there’s plenty of precedent for the flight of migrant workers during a crisis – the 2005 floods in Mumbai witnessed many workers fleeing the city. Half of the city’s population, mostly migrants, had also fled the city – then Bombay – in the wake of the 1918 Spanish flu.

When plague broke out in western India in 1994 there was an “almost biblical exodus of hundreds of thousands of people from the industrial city of Surat [in Gujarat]”, recounts historian Frank Snowden in his book Epidemics and Society.

Half of Bombay’s population deserted the city, during a previous plague epidemic in 1896. The draconian anti-plague measures imposed by the British rulers, writes Dr Snowden, turned out to be a “blunt sledgehammer rather than a surgical instrument of precision”. They had helped Bombay to survive the epidemic, but “the fleeing residents carried the disease with them, thereby spreading it.”

More than a century later, that same fear haunts India today. Hundreds of thousands of the migrants will eventually reach home, either by foot, or in packed buses. There they will move into their joint family homes, often with ageing parents. Some 56 districts in nine Indian states account for half of inter-state migration of male workers, according to a government report. These could turn out to be potential hotspots as thousands of migrants return home.

Image copyright GETTY IMAGES

Image copyright GETTY IMAGESPartha Mukhopadhyay, a senior fellow at Delhi’s Centre for Policy Research, suggests that 35,000 village councils in these 56 potentially sensitive districts should be involved to test returning workers for the virus, and isolate infected people in local facilities.

In the end, India is facing daunting and predictable challenges in enforcing the lockdown and also making sure the poor and homeless are not fatally hurt. Much of it, Dr Snowden told me, will depend on whether the economic and living consequences of the lockdown strategy are carefully managed, and the consent of the people is won. “If not, there is a potential for very serious hardship, social tension and resistance.” India has already announced a $22bn relief package for those affected by the lockdown.

The next few days will determine whether the states are able to transport the workers home or keep them in the cities and provide them with food and money. “People are forgetting the big stakes amid the drama of the consequences of the lockdown: the risk of millions of people dying,” says Nitin Pai of Takshashila Institution, a prominent think tank.

“There too, likely the worst affected will be the poor.”

Source: The BBC

India and Pakistan: How the war was fought in TV studios

As tensions between India and Pakistan escalated following a deadly suicide attack last month, there was another battle being played out on the airwaves. Television stations in both countries were accused of sensationalism and partiality. But how far did they take it? The BBC’s Rajini Vaidyanathan in Delhi and Secunder Kermani in Islamabad take a look.

It was drama that was almost made for television.

The relationship between India and Pakistan – tense at the best of times – came to a head on 26 February when India announced it had launched airstrikes on militant camps in Pakistan’s Balakot region as “retaliation” for a suicide attack that had killed 40 troops in Indian-administered Kashmir almost two weeks earlier.

A day later, on 27 February, Pakistan shot down an Indian jet fighter and captured its pilot.

Abhinandan Varthaman was freed as a “peace gesture”, and Pakistan PM Imran Khan warned that neither country could afford a miscalculation, with a nuclear arsenal on each side.

Suddenly people were hooked, India’s TV journalists included.

So were they more patriots than journalists?

Rajini Vaidyanathan: Indian television networks showed no restraint when it came to their breathless coverage of the story. Rolling news was at fever pitch.

The coverage often fell into jingoism and nationalism, with headlines such as “Pakistan teaches India a lesson”, “Dastardly Pakistan”, and “Stay Calm and Back India” prominently displayed on screens.

Some reporters and commentators called for India to use missiles and strike back. One reporter in south India hosted an entire segment dressed in combat fatigues, holding a toy gun.

And while I was reporting on the return of the Indian pilot at the international border between the two countries in the northern city of Amritsar, I saw a woman getting an Indian flag painted on her cheek. “I’m a journalist too,” she said, as she smiled at me in slight embarrassment.

Print journalist Salil Tripathi wrote a scathing critique of the way reporters in both India and Pakistan covered the events, arguing they had lost all sense of impartiality and perspective. “Not one of the fulminating television-news anchors exhibited the criticality demanded of their profession,” she said.

Secunder Kermani: Shortly after shooting down at least one Indian plane last week, the Pakistani military held a press conference.

As it ended, the journalists there began chanting “Pakistan Zindabad” (Long Live Pakistan). It wasn’t the only example of “journalistic patriotism” during the recent crisis.

Two anchors from private channel 92 News donned military uniforms as they presented the news – though other Pakistani journalists criticised their decision.

But on the whole, while Indian TV presenters angrily demanded military action, journalists in Pakistan were more restrained, with many mocking what they called the “war mongering and hysteria” across the border.

In response to Indian media reports about farmers refusing to export tomatoes to Pakistan anymore for instance, one popular presenter tweeted about a “Tomatical strike” – a reference to Indian claims they carried out a “surgical strike” in 2016 during another period of conflict between the countries.

Media analyst Adnan Rehmat noted that while the Pakistani media did play a “peace monger as opposed to a warmonger” role, in doing so, it was following the lead of Pakistani officials who warned against the risks of escalation, which “served as a cue for the media.”

What were they reporting?

Rajini Vaidyanathan: As TV networks furiously broadcast bulletins from makeshift “war rooms” complete with virtual reality missiles, questions were raised not just about the reporters but what they were reporting.

Indian channels were quick to swallow the government version of events, rather than question or challenge it, said Shailaja Bajpai, media editor at The Print. “The media has stopped asking any kind of legitimate questions, by and large,” she said. “There’s no pretence of objectiveness.”

In recent years in fact, a handful of commentators have complained about the lack of critical questioning in the Indian media.

“For some in the Indian press corps the very thought of challenging the ‘official version’ of events is the equivalent of being anti-national”, said Ms Bajpai. “We know there have been intelligence lapses but nobody is questioning that.”

Senior defence and science reporter Pallava Bagla agreed. “The first casualty in a war is always factual information. Sometimes nationalistic fervour can make facts fade away,” he said.

This critique isn’t unique to India, or even this period in time. During the 2003 Iraq war, western journalists embedded with their country’s militaries were also, on many occasions, simply reporting the official narrative.

Secunder Kermani: In Pakistan, both media and public reacted with scepticism to Indian claims about the damage caused by the airstrikes in Balakot, which India claimed killed a large number of Jaish-e-Mohammad (JeM) militants in a training camp.

Hamid Mir, one of the most influential TV anchors in the country travelled to the area and proclaimed, “We haven’t seen any such (militant) infrastructure… we haven’t seen any bodies, any funerals.”

“Actually,” he paused, “We have found one body… this crow.” The camera panned down to a dead crow, while Mr Mir asked viewers if the crow “looks like a terrorist or not?”

There seems to be no evidence to substantiate Indian claims that a militant training camp was hit, but other journalists working for international outlets, including the BBC, found evidence of a madrassa, linked to JeM, near the site.

A photo of a signpost giving directions to the madrassa even surfaced on social media. It described the madrassa as being “under the supervision of Masood Azhar”. Mr Azhar is the founder of JeM.

The signpost’s existence was confirmed by a BBC reporter and Al Jazeera, though by the time Reuters visited it had apparently been removed. Despite this, the madrassa and its links received little to no coverage in the Pakistani press.

Media analyst Adnan Rehmat told the BBC that “there was no emphasis on investigating independently or thoroughly enough” the status of the madrassa.

In Pakistan, reporting on alleged links between the intelligence services and militant groups is often seen as a “red line”. Journalists fear for their physical safety, whilst editors know their newspapers or TV channels could face severe pressure if they publish anything that could be construed as “anti-state”.

Who did it better: Khan or Modi?

Rajini Vaidyanathan: With a general election due in a few months, PM Narendra Modi continued with his campaign schedule, mentioning the crisis in some of his stump speeches. But he never directly addressed the ongoing tensions through an address to the nation or a press conference.

This was not a surprise. Mr Modi rarely holds news conference or gives interviews to the media. When news of the suicide attack broke, Mr Modi was criticised for continuing with a photo shoot.

The leader of the main opposition Congress party, Rahul Gandhi, dubbed him a “Prime Time Minister” claiming the PM had carried on filming for three hours. PM Modi has also been accused of managing his military response as a way to court votes.

At a campaign rally in his home state of Gujarat he seemed unflustered by his critics, quipping “they’re busy with strikes on Modi, and Modi is launching strikes on terror.”

Secunder Kermani: Imran Khan won praise even from many of his critics in Pakistan, for his measured approach to the conflict. In two appearances on state TV, and one in parliament, he appeared firm, but also called for dialogue with India.

His stance helped set the comparatively more measured tone for Pakistani media coverage.

Officials in Islamabad, buoyed by Mr Khan’s decision to release the captured Indian pilot, have portrayed themselves as the more responsible side, which made overtures for peace.

On Twitter, a hashtag calling for Mr Khan to be awarded a Nobel Peace Prize was trending for a while. But his lack of specific references to JeM, mean internationally there is likely to be scepticism, at least initially, about his claims that Pakistan will no longer tolerate militant groups targeting India.

Source: The BBC

Posted in Adnan Rehmat, airstrikes, airwaves, Al Jazeera, Balakot, BBC, BBC reporter, campaign schedule, casualty, combat fatigues, commentators, congress party, critical questioning, Dastardly Pakistan, Delhi, escalation, factual information, fought, general election, Hamid Mir, hashtag, Imran Khan, India alert, Indian jet fighter, international border, Islamabad, Islamist militant groups, Jaish-e-Mohammad (JeM), JeM, jingoism and nationalism, Journalist, Kashmir, madrassa, Masood Azhar, Media analyst, media editor, militant camps, militants, missiles, nationalistic fervour, Nobel Peace Prize, Pakistan, Pakistani, Pakistani military, Pallava Bagla, pilot, PM Narendra Modi, press, press conference, Prime Time Minister, rahul gandhi, Rajini Vaidyanathan, red line, retaliation, Reuters, Salil Tripathi, Secunder Kermani, Senior defence and science reporter, sensationalism and partiality, Shailaja Bajpai, signpost's, suicide attack, Surgical strike, The Print, Tomatical strike, toy gun, training camp, TV anchors, TV journalists, TV studios, Twitter, Uncategorized, war, war mongering and hysteria, warmonger, Wg Cdr Abhinandan Varthaman | Leave a Comment »