A factory in China has denied it used forced labour after a six-year-old girl found a message from workers inside a Tesco charity Christmas card.

The card supplier, Zhejiang Yunguang Printing, told China’s Global Times it had “never done such a thing”.

Tesco halted production at the factory on Sunday over the message, allegedly written by prisoners claiming they were “forced to work against our will”.

The Chinese foreign ministry said the allegation was “a farce”.

Speaking to the nationalist newspaper Global Times on Monday, a spokesman for the card supplier said: “We only became aware of this when some foreign media contacted us. We have never done such a thing.

“Why did they include our company’s name?”

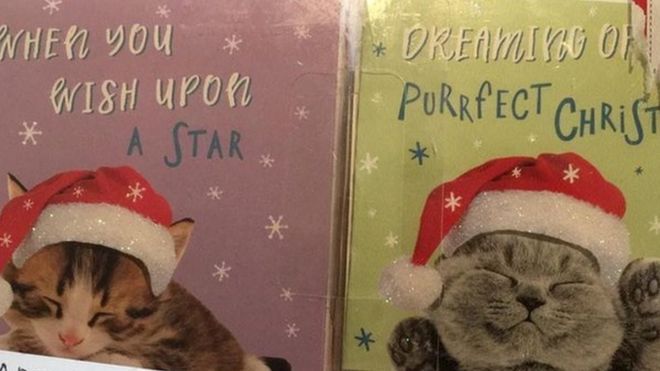

The message – first reported by the Sunday Times – was found by Florence Widdicombe, who was writing cards to her school friends. She found that one of them – featuring a kitten with a Santa hat – had already been written in.

In block capitals, it said: “We are foreign prisoners in Shanghai Qingpu prison China. Forced to work against our will. Please help us and notify human rights organisation.”

The message in the card asked whoever found the message to contact Peter Humphrey, a British journalist who was himself imprisoned there four years ago.

Chinese foreign ministry spokesman Geng Shuang told reporters on Monday the allegation was “a farce” created by Mr Humphrey.

“Shanghai’s Qingpu prison has no such foreign prisoners undergoing forced labour,” Mr Shuang said.

Zhejiang Yunguang Printing’s factory manager, Shu Yunjia, told the BBC it had not outsourced any of its work to the Qingpu prison.

Florence, from Tooting in south London, said she was writing her “sixth or eighth card” when she saw “somebody had already written in it”.

“It made me feel shocked,” she said, adding that when it was explained to her what the message meant she felt “sad”.

Tesco added that it would de-list Zhejiang Yunguang if it was found to have used prison labour.

A Tesco spokeswoman said: “We were shocked by these allegations and immediately halted production at the factory where these cards are produced and launched an investigation.”

The supermarket said it has a “comprehensive auditing system” to ensure suppliers are not exploiting forced labour.

The factory in question was checked only last month and no evidence of it breaking the ban on prison labour was found, it said.

Sales of charity Christmas cards at the company’s supermarkets raise £300,000 a year for the British Heart Foundation, Cancer Research UK and Diabetes UK.

Tesco has not received any other complaints from customers about messages inside Christmas cards.

‘Very bleak life’

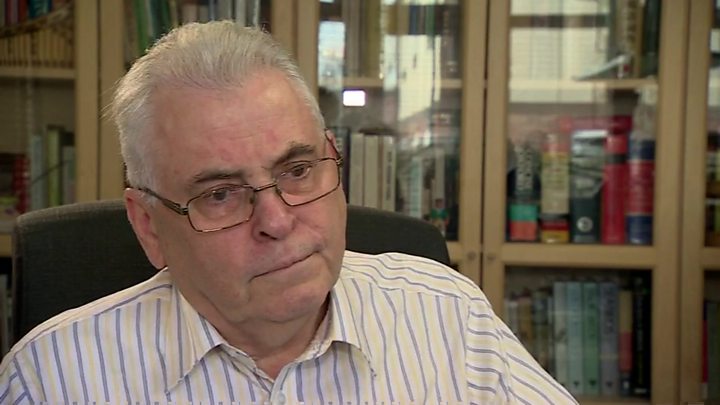

The message in the card urged the recipient to contact Peter Humphrey, who was formerly imprisoned at Qingpu on what he described as “bogus charges that were never heard in court”.

After the Widdicombe family sent him a message via Linkedin, Mr Humphrey said he then contacted ex-prisoners who confirmed inmates had been forced to work.

Mr Humphrey told the BBC that the cell block of foreign prisoners has about 250 people in it, who are living a “very bleak daily life” with 12 prisoners per cell.

He added that when he was in there, manufacturing labour work was voluntary – to earn money to buy soap or toothpaste – but that work has now become compulsory.

Mr Humphrey told the BBC: “I spent two years in captivity in Shanghai between 2013 and 2015 and my final nine months of captivity was in this very prison in this very cell block where this message has come from.

“So this was written by some of my cellmates from that period who are still there serving sentences.

“I’m pretty sure this was written as a collective message. Obviously one single hand produced this capital letters’ handwriting and I think I know who it was, but I will never disclose that name.”

It is not the first time that prisoners in China have reportedly smuggled out messages in products they have been forced to make for Western markets.

In 2012, Julie Keith from Portland, Oregon, discovered an account of torture and persecution by a prisoner who said he was forced to manufacture the Halloween decorations she had purchased.

And in 2014, Karen Wisinska from Co Fermanagh in Northern Ireland, found a note on a pair of Primark trousers reading: “Our job inside the prison is to produce fashion clothes for export. We work 15 hours per day and the food we eat wouldn’t even be given to dogs or pigs.”

Under the UN’s guidance for human rights and prisons, prisoners “should not be subordinated merely to making a profit either for the prison authorities or for a private contractor”.

The standard minimum rules for the treatment of prisoners state: “Prison labour must not be of an afflictive nature.”