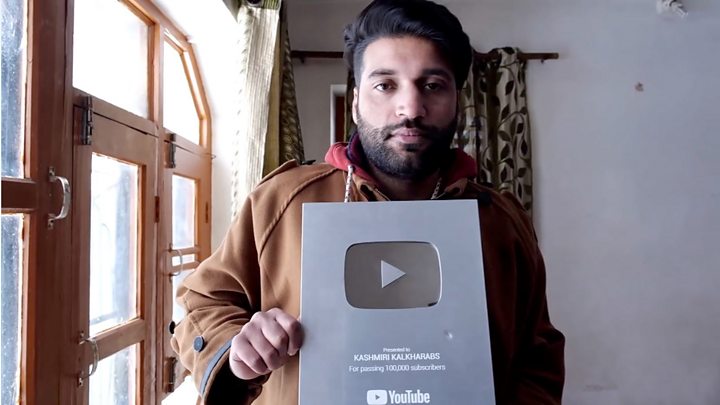

Image copyright MUKHTAR ZAHOOR

Image copyright MUKHTAR ZAHOORJournalists in Indian-administered Kashmir are struggling to make ends meet amid a months-long communications blockade that has only partially been lifted. The BBC’s Priyanka Dubey visited the region to find out more.

Muneeb Ul Islam, 29, had worked as a photo-journalist in Kashmir for five years, his pictures appearing in several publications in India and abroad.

But the young photographer’s dream job vanished almost overnight in August last year, when India’s federal government suspended landline, mobile and internet services in Kashmir.

The government’s move came a day before its announcement that it was revoking the region’s special status – a constitutionally-guaranteed provision, which gave Kashmir partial autonomy in matters related to property ownership, permanent residency and fundamental rights.

The controversial decision catapulted the Muslim-majority valley into global news – but local journalists like Mr Islam had no way to report on what was going on. And worse, they had to find other things to do because journalism could no longer pay the bills.

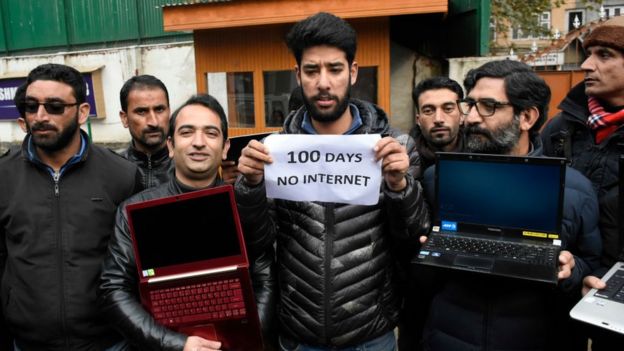

By January, the region had not had access to the internet for more than 150 days, India’s longest such shutdown.

“I chose journalism because I wanted to do something for my people,” Mr Islam explains. “I covered this conflict-ridden region with dedication until the loss of Kashmir’s special status put a full stop on my journey.”

In January, the government eased restrictions and allowed limited broadband service in the Muslim-majority valley, while 2G mobile coverage resumed in parts of the neighbouring Jammu region. But mobile internet and social media are still largely blocked.

India says this is necessary to maintain law and order since the region saw protests in August, and there has also been a long-running insurgency against Indian rule. But opposition leaders and critics of the move say the government cannot leave these restrictions in place indefinitely.

Meanwhile, journalists like Mr Islam are struggling.

Image copyright GETTY IMAGES

Image copyright GETTY IMAGESFor months, Mr Islam says, he kept trying to report and file stories and photos.

In September, he even spent 6,000 rupees ($84; £65) of his own money to make two trips to the capital, Srinagar, for a story. But he soon ran out of funds and had to stop.

He then tried to file his stories on a landline phone: he would call and read them aloud to someone on the other side who could type it out. But, as he found out, his stories didn’t earn him enough money to cover the cost of travelling for hours in search of a working landline.

Read more on Kashmir

- What happened in Kashmir and why it matters

- ‘Even I will pick up a gun’: Inside Kashmir’s lockdown

- The Indians celebrating Kashmir’s loss of autonomy

And Mr Islam was desperate for money because his wife was ill. So he eventually asked his brother for help, finding work carrying bricks on a construction site in his neighbourhood in Anantnag city. It pays him 500 rupees a day.

Mr Islam is not the only journalist in Kashmir who has been forced to abandon their career for another job.

Another journalist, who did not want to reveal his name, says he had been working as a reporter for several years, but quit the profession in August. He now plans to work in a dairy farm.

Image copyright MUKHTAR ZAHOOR

Image copyright MUKHTAR ZAHOORYet another reporter, who also also wished to remain anonymous, says he used to earn enough to comfortably provide for his family. Now, he barely has money to buy petrol for his motorcycle.

“I have no money because I have not been able to file any story in the last six months,” a third reporter, who spoke to the BBC on the condition of anonymity, says. “My family keeps telling me to find another job. But what else can I do?”

- The Kashmiris detained more than 700km away from home

- The complicated truth behind Kashmir’s ‘normality’

- Kashmiris allege torture in army crackdown

In December, people were given limited access to the internet at a government office in Anantnag, but this hasn’t helped local journalists. The office, Mr Islam says, is always crowded and there are only four desktops for a scrum of officials, students and youngsters who want to log on to respond to emails, fill exam forms, submit job applications or even check their social media.

“We have access for only for a few minutes and the internet speed is slow,” he explains. “We are barely able to access email, forget reading the news.”

What’s more, Mr Islam says those who work at the office often ask customers to show them the contents of emails. “This makes us uncomfortable, but we don’t have a choice.”

Image copyright MUKHTAR ZAHOOR

Image copyright MUKHTAR ZAHOORMany journalists say that they have been completely cut off from their contacts for months now, making it hard to to maintain their networks or sources.

They also speak of how humiliating it is to beg for wi-fi passwords and hotspots at the cramped media centre in Srinagar, which has less than two dozen computers for hundreds of journalists.

This has left publishers in the lurch too. “My reporters and writers are not able to file,” says Basheer Manzar, the editor of Kashmir Images.

He still publishes a print edition, he says, because if he doesn’t do so for a certain number of days in the month, he will lose the license.

But the website continues to struggle, he adds, because most of the readers in Indian-administered Kashmir have no access to the internet.

“I know what is happening in New York through news on the TV, but I don’t know what’s happening in my hometown.”

Source: The BBC