Image copyrigh tGETTY IMAGES

Image copyrigh tGETTY IMAGESIndia’s second Moon mission will see the country’s space agency attempt to land a rover on the lunar surface on 7 September. Science writer Pallava Bagla explains how it will reach the Moon and why it is significant.

Why is this mission unique?

Costing $150 million, Chandrayaan-2 will carry forward the achievements of its predecessor Chandrayaan-1 which was launched in 2008 and discovered the presence of water molecules on the parched lunar surface.

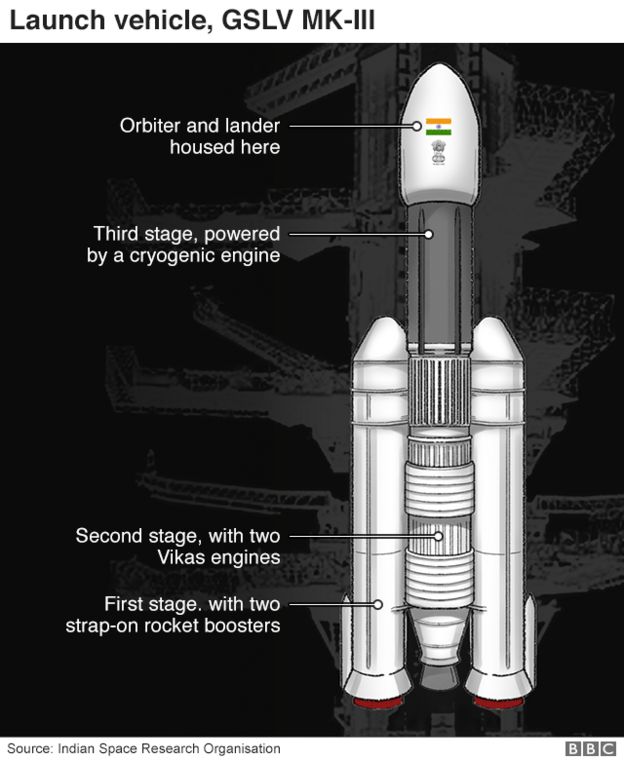

Chandrayaan-2 is a three-in-one mission comprising an orbiter, a lander named Vikram and a six-wheeled rover named Pragyaan.

It was launched on 22 July, a week after its scheduled blast-off, which was halted due to a technical snag.

It entered the Moon’s orbit nearly a month later in a tricky operation, completing a series of manoeuvres before its lander was cut loose on 2 September.

Now, on 7 September, a little after midnight India local time (1800 GMT), the lander which contains the rover will be sent hurtling down to the lunar surface where it is expected to make a landing near the South Pole of the Moon.

The last 15 minutes of the mission, when the Vikram lander will attempt to autonomously guide itself down to the lunar surface with no support from ground control, has been described as “15 minutes of terror” by the head of the Indian Space Research Organisation (Isro), Dr K Sivan.

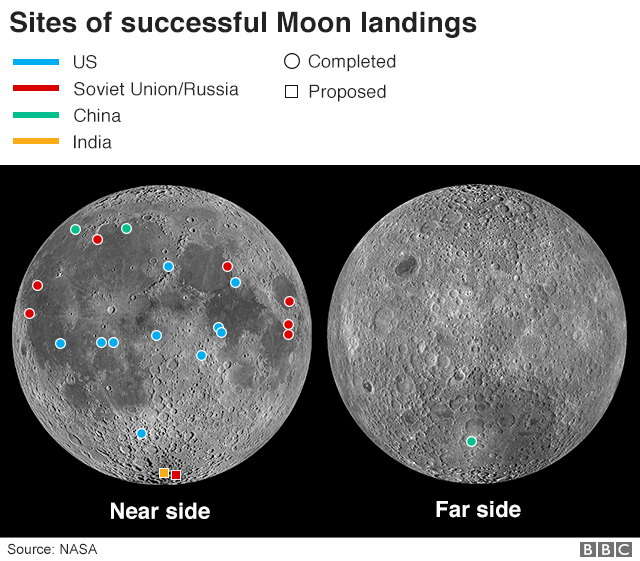

If India does succeed in touching down with the Vikram lander intact, it will become the fourth country to do so after the US, Russia and China.

More importantly for Indians, it will mean the nation’s flag will reach the Moon intact.

How will it land on the Moon?

The Moon may be Earth’s closest neighbour, but landing on it is a very tricky operation.

It has no atmosphere worthy of the name, which means parachutes cannot be used to slow the lander’s descent to the surface. The only option therefore is to go in for what is called a “powered descent”.

This means that the velocity of the lander is steadily reduced with its own rocket engines.

The lander will be moving horizontally across the surface of the Moon as it descends. The rocket engines must bring that horizontal movement to a stop whilst at the same time controlling the rate of descent to near zero just before the moment of touchdown.

This is known as a “soft landing”.

If the lander does not function properly it could crash land on the Moon surface, like its predecessor Chandrayaan-1 – though this was an intentional crash landing as in 2008 India had not yet mastered how to perform a soft landing.

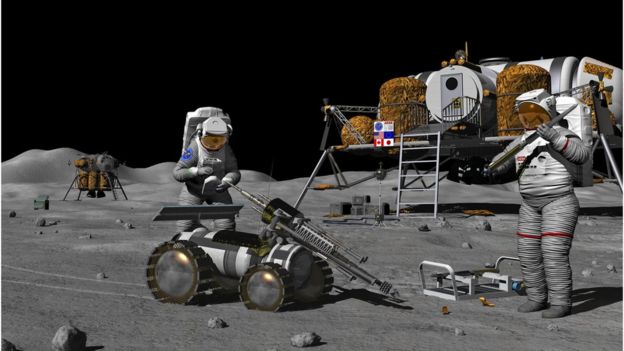

Either way, once the landing happens and the lunar dust that may have been kicked up settles, the ramp opens up and the rover is very gently wheeled out.

- Chandrayaan-2: India launches second Moon mission

- India spacecraft begins orbiting Moon

- Is India ready to send someone to space?

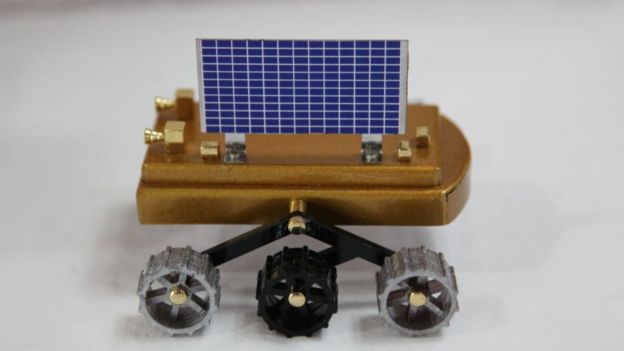

The rover will then “Moon walk” at the princely speed of one centimetre per minute. It can travel a maximum of 500m (1,640ft) from the lander.

Both the lander and rover are powered with solar batteries and carry three instruments apiece.

What will the lander do?

The lander will, among other things, measure Moon quakes in its vicinity and do a thermal profile of the lunar “soil”. Meanwhile, the rover will further analyse the lunar soil.

The rear wheels of the rover are imprinted with the national emblem – the Ashoka Chakra – and the Isro logo, which means a permanent mark of India’s visit will be left on the surface of the Moon.

But the extreme temperatures on the Moon’s surface are a real challenge to the mission.

Image copyright GETTY IMAGES

Image copyright GETTY IMAGESWhen the Sun shines, the lunar temperature can cross 100C and when it sets the temperature can drop to -170C.

As their batteries must be recharged with sunlight, the nominal life of both the rover and lander is expected to be one lunar day, since Isro is not sure if they can survive the ultra-cold temperatures of the long cold lunar night which lasts 14 days.

Both will send back photos of each other so the first Indian “selfies” from the lunar surface are expected soon after they land.

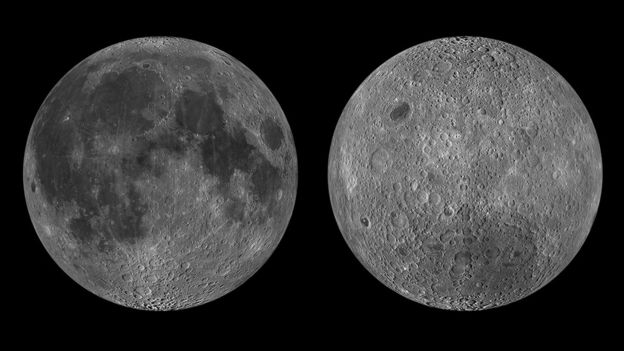

Why is the South Pole of the Moon significant?

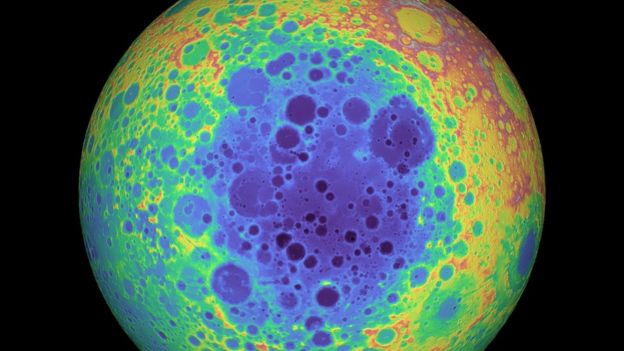

The South Pole of the Moon is still a largely unexplored area, and India is targeting a spot that no other landing craft has reached so far. The mission will attempt to soft land its rover and lander in a high plain between two craters – Manzinus C and Simpelius N – at a latitude of about 70° south.

Most earlier missions including the Apollo manned missions targeted the equatorial region of the Moon.

Isro says the lunar South Pole is especially interesting because the surface area that remains in shadow here is much larger than that of the Moon’s North Pole. This means that there is a possibility of water in areas that are permanently shadowed.

This unexplored region is also especially important because in the near future, possibly by 2024, the US space agency Nasa aims to place boots back on the Moon through its Artemis Mission, and wants to target landing near the South Pole.

India’s mission will therefore give the Americans much needed data of this unchartered territory.

Why will the orbiter circle the Moon for a year?

The Chandrayaan-2 orbiter is expected to circle the Moon for a further year.

During that time, it will map lunar minerals, take high resolution photos and search for water on the lunar surface in the most detailed fashion till date by any lunar craft, using an infra-red imager and radars.

Image copyright GETTY IMAGES

Image copyright GETTY IMAGESThe high resolution camera will help make a digital terrain map of the moon

It will also analyse the thin lunar atmosphere.

There is also the possibility that the orbiter may last longer than a year, as Isro says it has made suitable savings in fuel. But once its fuel runs out, the orbiter will become a long-lasting Indian-made lunar satellite.

Source: The BBC