Image copyright GETTY IMAGES

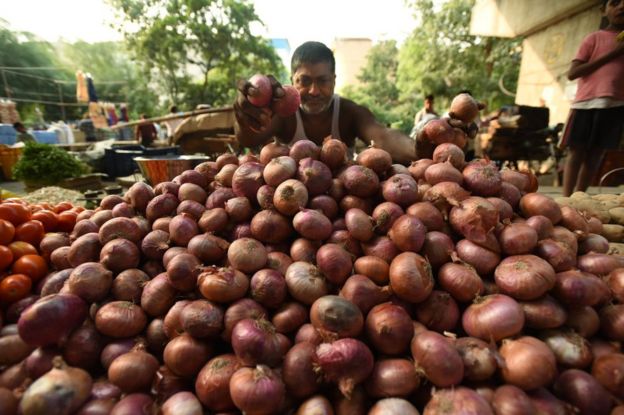

Image copyright GETTY IMAGESOnion prices have yet again dominated the headlines in India over the past week. BBC Marathi’s Janhavee Moole explains what makes this sweet and pungent vegetable so political.

The onion – ubiquitous in Indian cooking – is widely seen as the poor man’s vegetable.

But it also has the power to tempt thieves, destroy livelihoods and – with its fluctuating price a measure of inflation – end the careers of some of India’s most powerful politicians.

With that in mind, it’s perhaps unsurprising those politicians might be feeling a little concerned this week.

So, what exactly is happening with India’s onions?

In short: its price has skyrocketed.

Onion prices had been on the rise in India since August, when 25 rupees ($0.35; £0.29) would have got you a kilo. At the start of October, that price was 80 rupees ($1.13; £0.91).

Fearing a backlash, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)-led government banned onion exports, hoping it would bring down the domestic price. And it did.

Image copyright GETTY IMAGES

Image copyright GETTY IMAGESA kilo was selling for less than 30 rupees on Thursday at Lasalgaon, Asia’s largest onion wholesale market, located in the western state of Maharashtra.

However, not everyone is happy.

While high prices had angered consumers in a sluggish Indian economy, the fall in prices sparked protests by exporters and farmers in Maharashtra, where state elections are due in weeks.

And it is not just at home where hackles have been raised: the export ban has also strained trade relations between India and its neighbour, Bangladesh, which is among the top importers of the vegetable.

But why does the onion matter so much?

The onion is a staple vegetable for the poor, indispensable to many Indian cuisines and recipes, from spicy curries to tangy relishes.

“In Maharashtra, if there are no vegetables or you can’t afford to buy vegetables, people eat ‘kanda bhakari’ [onion with bread],” explains food historian Dr Mohseena Mukadam.

True, onions are not widely used in certain parts of the country, such as the south and the east – and some religious communities don’t eat them at all.

But they are especially popular in the more populous northern states which – notably – send a higher number of MPs to India’s parliament.

“Consumers in northern India wield more power over the federal government. So although consumers in other parts of India don’t complain as much about higher prices, if those in northern India do, the government feels the pressure,” says Milind Murugkar, a policy researcher.

Image copyright GETTY IMAGES

Image copyright GETTY IMAGESA drop in prices also affects the income of onion farmers, mainly in Maharashtra, Karnataka in the south and Gujarat in the west.

“Farmers see the onion as a cash crop that grows in the short term, and grows well in dry areas with less water,” says Dipti Raut, a journalist, who has been on the “onion beat” for years.

“It’s like an ATM machine that guarantees income to farmers and sometimes, their household budget depends on the onion produce,” she said.

Onions have even attracted robbers: when prices skyrocketed in 2013, thieves tried to steal a truck loaded with onions, but were caught by the police.

Why do politicians care about the onion?

Put simply, because the price moving too far one way or another is likely to anger a large block of voters, be they everyday households, or the country’s farmers.

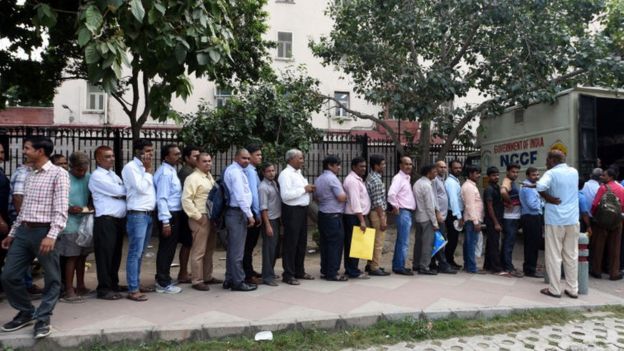

Image copyright GETTY IMAGES

Image copyright GETTY IMAGESOnions are so crucial they have even featured in election campaigns. The Delhi state government bought and sold them at subsidised rates in September when prices were at their peak: chief minister Arvind Kejriwal, it should be noted, is up for re-election next year.

Meanwhile, Indira Gandhi swept to power in 1980 on slogans that used soaring onion prices as a metaphor for the economic failures of the previous government.

But why did onion prices rise this year?

A drop in supply, due to heavy rains and flooding destroying the crop in large parts of India, and damaging some 35% of the onions stocks in storage, according to Nanasaheb Patil, director of the National Agricultural Co-operative Marketing Federation.

He said the flooding had also delayed the next round of produce, which was due in September.

Image copyright GETTY IMAGES

Image copyright GETTY IMAGES“This has become a fairly regular phenomenon in recent decades,” Mr Murugkar said. “Onion prices swing heavily with a small drop or increase in production.”

In fact, the shortage – and subsequent rise in prices – happens almost every year around this time, according to Ms Raut.

“It’s a vicious cycle and the trader lobby and middlemen benefit from even the slightest price fluctuations,” she added.

What’s the solution?

Ms Raut says more grass-root planning and better storage facilities and food processing services will ease the problem – and making a variety of cash crops and vegetables available across the country would also ease the pressure on onions.

“The government is quick to act when onion prices rise. Why don’t they act as swiftly when prices fall?” asked Vikas Darekar, an onion farmer in Maharashtra. He said the government should buy onions from farmers at a “fair price”.

Mr Murugkar, however, feels that the government should never interfere in “onion matters”.

“If you are interested in raising purchasing power of the people, they should not curtail exports. Do we have such a ban on software exports? It’s really absurd. A government which has won such a huge majority should be able to withstand the pressures from a few consumers.”

Source: The BBC