- Black market imports from China, confusing regulations and pollution concerns are undermining India’s fireworks industry

- Industry sources say Diwali sales this year were down by 30 per cent

Arumugam Chinnaswamy set up his makeshift booth selling firecrackers in a Chennai neighbourhood a week ahead of Diwali, the Hindu festival of lights, with great expectations of doing a brisk trade.

Yet a week later, he has been forced to pack up more than half his stock in the hope he’ll have better luck next year.

“Four years ago, I sold firecrackers worth 800,000 rupees (US$11,288) on the eve of Diwali alone. This year, the sales have not even been a quarter of that,” said Chinnaswamy, 65, painting a grim picture that will be recognised by many in the Indian fireworks industry.

Chinnaswamy buys his firecrackers in Sivakasi, an industrial town in the southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu that produces more than 90 per cent of the country’s fireworks.

But this reputation is under threat, struggling under the weight of an anti-pollution campaign, regulatory uncertainty and the arrival of cheap black-market Chinese imports. Irregular monsoons and a slowdown-induced cash crunch have not helped matters either.

Industry figures estimate the Diwali sales of India’s 80 billion-rupee firecracker industry took a 30 per cent drop this year.

A TOXIC PROBLEM

With pollution in Indian cities among the worst in the world, the government has come under pressure to do something about the nation’s toxic air – a problem that becomes more acute during Diwali due to the toxic fumes emitted when celebratory fireworks are set off. This Diwali, for instance, many areas in New Delhi recorded an Air Quality Index (AQI) of 999, the highest possible reading (the recommended limit is 60).

That makes the fireworks industry seem like an easy target when it comes to meeting government air quality targets.

Trouble began brewing in October last year when the Supreme Court banned the manufacture of traditional fireworks containing barium nitrate, a chief polluter. That decision put a rocket under the industry, as barium nitrate is cheap and is used in about 75 per cent of all firecrackers in India.

Factories in Sivakasi responded with a four-month shutdown protest that decimated annual production levels by up to a third.

Apparently realising it had overstepped the mark – and that enforcing the Supreme Court regulations would be next to impossible – the government stepped in to rescue the industry, offering its assistance in the manufacture of environment-friendly crackers containing fewer pollutants, but it was too little, too late.

“The Supreme Court verdict was simply Delhi-centric with the vague idea of [cracking down on] urban pollution. It lacked any on-the-ground knowledge of the fireworks industry,” said Tamil Selvan, president of the Indian Fireworks Association, which represents more than 200 medium and large manufacturers.

Singapore travellers give Hong Kong a miss over Diwali long weekend

“Fireworks are low-hanging fruit for the anti-pollution drive as the industry is unorganised. Could the government or judiciary place a similar blanket ban on more pollution-causing industries like automobiles, plastics or tobacco?” asked Selvan.

CHINESE COMPETITION

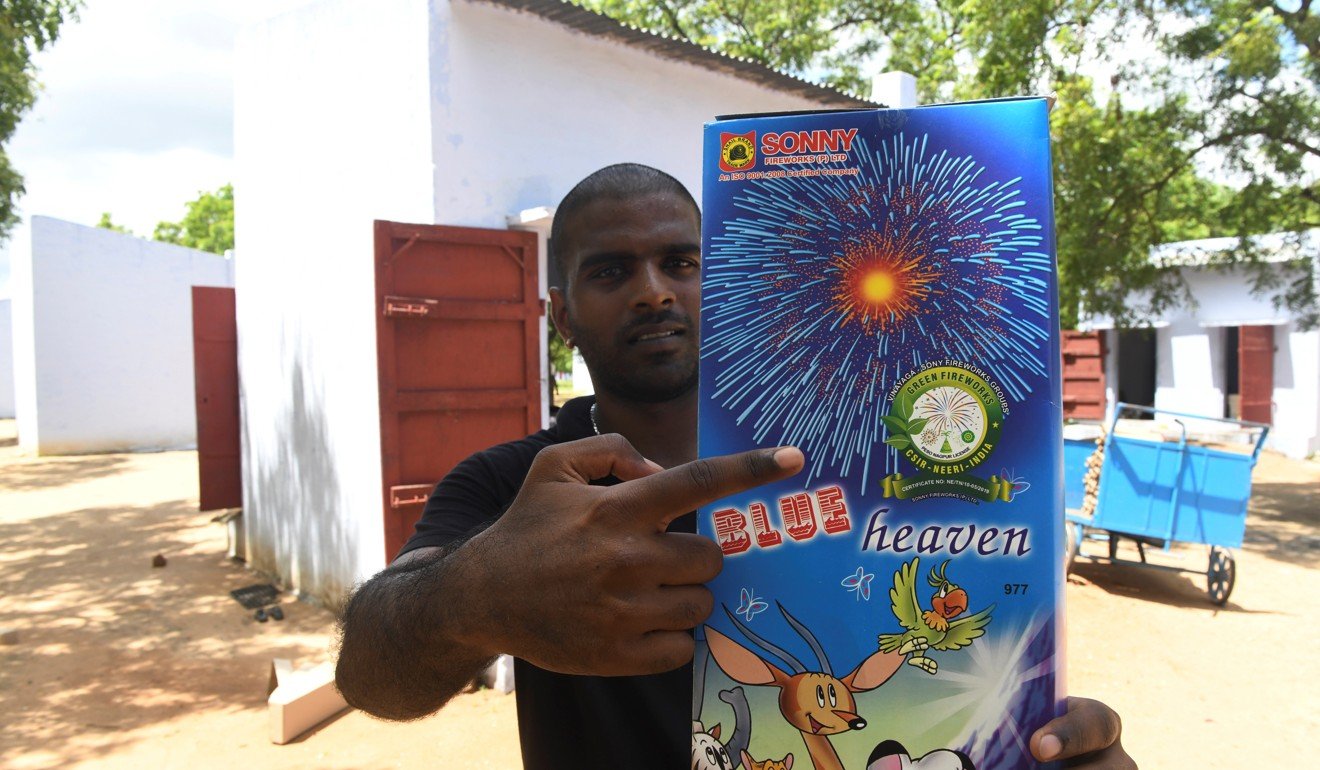

The industry has also been hit by a flood of cheap Chinese firecrackers that are smuggled into the country on the black market.

In September, the country’s federal anti-smuggling agency, the Directorate of Revenue Intelligence, cautioned various government departments that huge quantities of Chinese-produced firecrackers had reached Indian soil in the lead up to Diwali.

But industry sources complain they have seen little action from the government to combat the problem.

Legally, Indian manufacturers can neither import nor export firecrackers. The Indian firecracker industry is the second-largest in the world after China’s.

Raja Chandrashekar, chief of the Federation of Tamil Nadu Fireworks Traders, a lobbying body, said low-end Indian-manufactured firecrackers such as roll caps and dot caps – popular among children – had struggled to compete with Chinese-made pop pops and throw bombs.

“Despite our repeated complaints to government bodies, Chinese firecrackers find a way into India, particularly in the northern parts. This is severely affecting our business,” said Chandrashekar.

While more Chinese fireworks might be entering India, the effect has been to undermine the industry, resulting in fewer sales overall.

FIZZLING OUT?

The Sivakasi fireworks industry faces other problems, too. Not least among these is the use of child labour, which had been rampant until a government crackdown a few years ago, and the practice of some factories to operate without proper licences and with questionable safety standards.

But despite the darker aspects of the industry, its role goes beyond merely helping Diwali celebrations go with a bang every year.

India is crazy about gold. But can the love last as prices skyrocket?

“The livelihoods of over five million people who are indirectly involved in the business, in areas such as trade and transport, depend on the survival of the industry,” said Chandrashekar.

That survival looks increasingly in question. Dull sales of fireworks have been reported in major cities including New Delhi, Mumbai, Bangalore and Hyderabad, though exact numbers can be hard to come by due to the unregulated nature of the industry and unreliable numbers shared by manufacturers.

So great has the resultant outcry been that some cynics even wonder whether the industry is struggling as much as it claims or whether it is part of a ploy by manufacturers to gain more government concessions and avoid any further crackdown.

“These firecracker manufacturers lie through their teeth about the Diwali sales for self-serving motives such as tax avoidance. The overall business is healthy,” said Vijay Kumar, editor of the Sivakasi-based monthly magazine Pyro India News.

“Though there was a 30-40 per cent shortage in annual production, all the manufactured products have been sold this year. No large stockpile is left with any manufacturer.”

Still, regardless of the manufacturers’ motives, the result of the industry’s struggles has been that street sellers like Chinnaswamy have fewer fireworks to sell – and they are struggling even to sell those.

Chinnaswamy says people are confused about the government’s anti-pollution drive and about what firecrackers are now legal and this has discouraged them from buying. Despite the government’s effort to promote “green crackers” he says these are too hard to come by to be a ready solution, at least for this year.

“There was no clarity on what type of firecrackers, whether green crackers or otherwise, can be set off and at what time of the day. Many consumers even asked me whether or not the conventional firecrackers are totally banned while there was much misinformation floating about on social media,” said Chinnaswamy.

Shaking his head, all he can do is hope that next year his Diwali goes with more of a bang.

Source: SCMP