NEW DELHI (Reuters) – For years, Hindus and Muslims lived and worked peacefully together in Yamuna Vihar, a densely populated Delhi district.

But the riots that raged through the district last month appear to have cleaved lasting divisions in the community, reflecting a nationwide trend as tensions over the Hindu nationalist agenda of Prime Minister Narendra Modi boil over.

Many Hindus in Yamuna Vihar, a sprawl of residential blocks and shops dotted with mosques and Hindu temples, and in other riot-hit districts of northeast Delhi, say they are boycotting merchants and refusing to hire workers from the Muslim community. Muslims say they are scrambling to find jobs at a time when the coronavirus pandemic has heightened pressure on India’s economy.

“I have decided to never work with Muslims,” said Yash Dhingra, who has a shop selling paint and bathroom fittings in Yamuna Vihar. “I have identified new workers, they are Hindus,” he said, standing in a narrow lane that was the scene of violent clashes in the riots that erupted on Feb. 23.

The trigger for the riots, the worst sectarian violence in the Indian capital in decades, was a citizenship law introduced last year that critics say marginalises India’s Muslim minority. Police records show at least 53 people, mostly Muslims, were killed and more than 200 were injured.

Dhingra said the unrest had forever changed Yamuna Vihar. Gutted homes with broken doors can be seen across the neighbourhood; electricity cables melted in the fires dangle dangerously above alleys strewn with stones and bricks used as makeshift weapons in the riots.

Most Hindu residents in the district are now boycotting Muslim workers, affecting everyone from cooks and cleaners to mechanics and fruit sellers, he said.

“We have proof to show that Muslims started the violence, and now they are blaming it on us,” Dhingra said. “This is their pattern as they are criminal-minded people.”

Those views were widely echoed in interviews with 25 Hindus in eight localities in northeast Delhi, many of whom suffered large-scale financial damages or were injured in the riots. Reuters also spoke with about 30 Muslims, most of whom said that Hindus had decided to stop working with them.

Suman Goel, a 45-year-old housewife who has lived among Muslim neighbours for 23 years, said the violence had left her in a state of shock.

“It’s strange to lose a sense of belonging, to step out of your home and avoid smiling at Muslim women,” she said. “They must be feeling the same too but it’s best to maintain a distance.”

Mohammed Taslim, a Muslim who operated a business selling shoes from a shop owned by a Hindu in Bhajanpura, one of the neighbourhoods affected by the riots, said his inventory was destroyed by a Hindu mob.

He was then evicted and his space was leased out to a Hindu businessman, he said.

“This is being done just because I am a Muslim,” said Taslim.

Many Muslims said the attack had been instigated by hardline Hindus to counter protests involving tens of thousands of people across India against the new citizenship law.

“This is the new normal for us,” said Adil, a Muslim research assistant with an economic think tank in central Delhi. “Careers, jobs and business are no more a priority for us. Our priority now is to be safe and to protect our lives.”

He declined to disclose his full name for fear of reprisals.

Emboldened by Modi’s landslide electoral victory in 2014, hardline groups began pursuing a Hindu-first agenda that has come at the expense of the country’s Muslim minority.

Vigilantes have attacked and killed a number of Muslims involved in transporting cows, which are seen as holy animals by Hindus, to slaughterhouses in recent years. The government has also adopted a tough stance with regard to Pakistan, and in August withdrew semi-autonomous privileges for Jammu and Kashmir, India’s only Muslim-majority state.

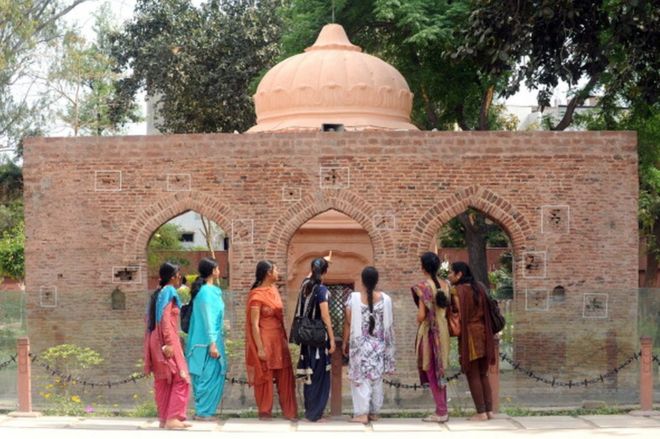

In November, the Supreme Court ruled that a Hindu temple could be built at Ayodhya, where a right-wing mob tore down a 16th-century mosque in 1992, a decision that was welcomed by the Modi government.

The citizenship law, which eases the path for non-Muslims from neighbouring Muslim-majority nations to gain citizenship in India, was the final straw for many Muslims, as well as secular Indians, sparking nationwide protests.

Modi’s office did not respond to questions from Reuters about the latest violence.

NIGHT VIGILANTES

During the day, Hindus and Muslims shun each other in the alleys of the Delhi districts that were hardest hit by the unrest in February. At night, when the threat of violence is greater, they are physically divided by barricades that are removed in the morning.

And in some areas, permanent barriers are being erected.

On a recent evening, Tarannum Sheikh, a schoolteacher, sat watching two welders install a high gate at the entrance of a narrow lane to the Muslim enclave of Khajuri Khas, where she lives. The aim was to keep Hindus out, she said.

“We keep wooden batons with us to protect the entrance as at any time, someone can enter this alley to create trouble,” she said. “We do not trust the police anymore.”

In the adjacent Hindu neighbourhood of Bhajanpura, residents expressed a similar mistrust and sense of insecurity.

“In a way these riots were needed to unite Hindus, we did not realise that we were surrounded by such evil minds for decades,” said Santosh Rani, a 52-year-old grandmother.

She said she had been forced to lower her two grandchildren from the first floor of her house to the street below after the building was torched in the violence, allegedly by a Muslim.

“This time the Muslims have tested our patience and now we will never give them jobs,” said Rani who owns several factories and retail shops. “I will never forgive them.”

Hasan Sheikh, a tailor who has stitched clothing for Hindu and Muslim women for over 40 years, said Hindu customers came to collect their unstitched clothes after the riots.

“It was strange to see how our relationship ended,” said Sheikh, who is Muslim. “I was not at fault, nor were my women clients, but the social climate of this area is very tense. Hatred on both sides is justified.”

Source: Reuters