The Terminal High Altitude Area Defence (THAAD) arrived in Seongju in September 2017. Photo: Reuters

Australia – like South Korea – is heavily dependent on trade with China, but is also closely bound to the US in defence and political terms, and Bishop feared that should Australia fall out of favour with Beijing, Australian companies could face similar risks, and so she sought the counsel of the politician, who asked not to be named.

The case of Canadian canola and meat exports being banned from China, reportedly in retaliation for the arrest of Huawei chief financial officer Meng Wanzhou, also known as Sabrina Meng and Cathy Meng, is an example of how third nations can be drawn into the modern day superpower rivalry.

Many analysts say the efforts of South Korean firms in China should be essential study material for Western governments and businesses about the political risks of doing business in the mainland, which are growing as the US-China trade war threatens to draw in other nations and expand into a broader geopolitical struggle.

But large South Korean firms have been gradually withdrawing from China for a number of years – even before the THAAD crisis – and have been able to leave on a managed basis. They are leaving to avoid a repeat of the political crisis that ruined Lotte’s China business, and to avoid tariffs on exports of their China-made products to the US.

Lotte have been forced to close retail operations in China. Photo: Reuters

Share:

But they are also leaving because Chinese firms have become much more competitive in the domestic market that South Korean companies had found so fruitful for more than a decade – a fate that could easily befall Western companies that are eyeing China’s burgeoning middle-class consumer market. Now, while American firms are considering exiting China and setting up in nations that have lower tariff access to the US, South

Korean competitors have had a few years’ head start.

“In a way, all the problems that some South Korean companies had since 2017 might be a blessing in disguise. It meant that they started all of this [supply chain shift] two years before all the other companies,” said Andrew Gilholm, Seoul-based director of analysis for China and Korea at political risk advisory, Control Risks.

Another chaebol, Samsung Electronics, opened its first plant in Vietnam in 2008 and this long-term presence has enabled it to build a supply chain of South Korean companies, which in turn makes it easier for other South Korean firms to establish a base in the Southeast Asian nation.

We have experienced some of the worst situations in China over the past few years and learnt that the political risk there wouldn’t just simply go away overnight Ex-Lotte Shopping manager

As a result, South Korean investment into Vietnam climbed to US$1.97 billion in the first half of 2018, exceeding the country’s investment in China of US$1.6 billion over the same period for the first time, according to the Export-Import Bank of Korea.

Overall in 2018, South Korea’s total investment to the Southeast Asian country totalled US$3.2 billion. Its exports to Vietnam also increased to US$48.6 billion, 121 times that of 1992, when the two countries established diplomatic relations, and the trend is expected to continue.

“We have experienced some of the worst situations in China over the past few years and learnt that the political risk there wouldn’t just simply go away overnight,” said a former manager of Lotte Shopping, the chaebol’s retail arm, who spoke on condition of anonymity.

“China may pass all the legislation ensuring the safety of foreign investments and the rights of multinational companies, but the chance of it swinging away again when there is another political confrontation is just too high … we cannot afford to take any more risk.”

China eventually lifted its economic sanctions on Lotte in April, and the municipal government of Shenyang, the capital of Liaoning province in Northeastern China, gave the company permission in May to resume work on the US$2.6 billion Lotte Town shopping and leisure development.

But according to a person close to the project, Lotte is considering selling the complex after its completion, as it does not wish to continue its retail business in China. A Lotte spokesman declined to comment, saying the situation is “complicated”.

On one hand, its eagerness to leave China reflects the volatility in the market, but on the other, its decision to complete the construction of project before leaving suggests an unwillingness to burn bridges in the process, analysts said.

Samsung is another South Korean giant downsizing its Chinese manufacturing presence after it closed its Shenzhen production line in May 2018, followed by its Tianjin factory in December.

Samsung has been very aware of the potential issues around those closuresJason Wright

Its last remaining mobile phone production line in

implementing a voluntary retirement programme. Samsung is also considering moving some television manufacturing from China to Vietnam, according to a company insider.

However, it too, is carefully managing its exit strategy, said Jason Wright, founder of Hong Kong-based intelligence firm Argo Associates, who is advising a growing number of South Korean companies seeking to leave China. Samsung is still a large supplier of microchips to Chinese companies like Huawei, and to exit on negative terms could disrupt its ongoing business.

“Samsung has been quite generous in the packages that have been offered [to workers in the factories that it has closed],” Wright said. “Samsung has been very aware of the potential issues around those closures.”

As well as the political risks and tariffs, Samsung has seen its mainland market share in several product queues shrink dramatically due to competition from Chinese rivals. Its share of China’s smartphone market, for example, fell from 20 per cent in 2013 to just 0.8 per cent last year, according to Strategy Analytics, a market research firm.

Over the same period, it has been moving its supply chain out of China in a “subtle and imperceptible” way, according to Julien Chaisse, a professor of trade law at City University of Hong Kong who has advised, among others, Lotte on its plans to relocate to Vietnam.

Samsung Electronics opened its first plant in Vietnam in 2008. Photo: Cissy Zhou

As stories emerged in June that Apple was considering a partial exit of China, it was impossible not to see parallels. iPhone sales in China fell 30 per cent in the first quarter of 2019, according to research firm Canalys, while smartphones will be among those facing a potential tariff of up to 25 per cent, although this has been at least delayed after the trade war truce agreed by

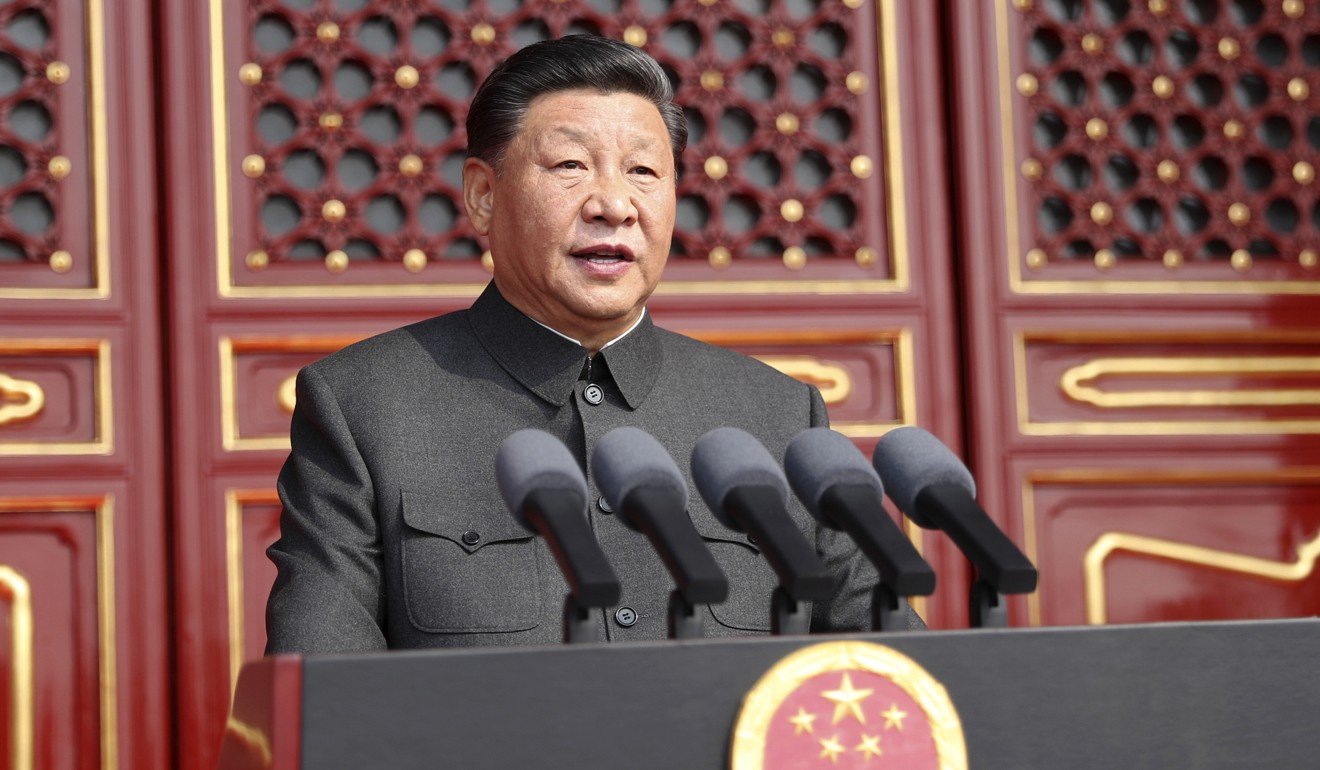

and Chinese President Xi Jinping at the

Meanwhile, South Korean car companies Kia and Hyundai’s combined market share in China fell to 2.7 per cent last year, from about 10 per cent at the beginning of the decade. Both companies, which have shared ownership, are downsizing their Chinese operations.

“In the past, China was just a great market, but for Korea, now China has become a competitor. So that is really a change in the dynamic over the last five years. China was not really able to compete with Korea in most areas,” said Wright from Argo Associates.

City University of Hong Kong professor Chaisse traces the exodus of South Korean firms back to 2014, before THAAD and before the trade war, and highlighted an arcane arbitration case at the United Nations’ dispute settlement courts as a turning point. After that case, South Korean companies in China faced an increasingly hostile environment.

Filed in 2014 and settled in 2017, the case emerged after South Korean company Ansung Housing had been forced to sell a golf resort it was developing in Eastern China after a change in the country’s real estate legislation.

Ansung took the case to an arbitration panel, claiming it breached a Sino-Korean investment treaty. The company won – only the second defeat for China in two decades of participation in the court, but this ushered in a “change in atmosphere” for South Korean firms.

“My take is that while the Korean case is unique for a number of reasons, it highlights what is going to happen to many other foreign companies operating in China,” Chaisse said.

“I think very soon even European companies will be reconsidering their businesses in China. Every time it will be a different story: different countries, different companies, in different economic sectors will have different reaction times and the magnitude of their withdrawal may vary.”

But for those now fleeing trade war tariffs, they may not have the luxury of long-term planning that companies like Samsung and Lotte have had, said Gilholm from Control Risks.

“Long term, I think the Korean firms that are moving out of China have had it easier because they haven’t had to do it under quite such pressured and scrutinised circumstances as a company which starts to move things now,” he said.

Source: SCMP