Image copyrightNETFLIX

Image copyrightNETFLIXThe Wandering Earth has been billed as a breakthrough for Chinese sci-fi.

The film tells the story of our planet, doomed by the expanding Sun, being moved across space to a safer place. The Chinese heroes have to save the mission – and humanity – when Earth gets caught in Jupiter’s gravitational pull.

Based on Hugo Award winner Liu Cixin’s short story of the same name, Wandering Earth has already grossed $600m (£464m) at the Chinese box office and was called China’s “giant leap into science fiction” by the Financial Times. It’s been bought by Netflix and will debut there on 30 April.

But while this may be the first time many in the West have heard of “kehuan” – Chinese science fiction – Chinese cinema has a long sci-fi history, which has given support to scientific endeavour, offered escapism from harsh times and inspired generations of film-goers.

So for Western audiences eager to plot the rise of the Chinese sci-fi movie, here are five films I think are worth renewed attention.

Dislocation

Huang Jianxin, 1986

For most in the Western world, their first encounter with Chinese cinema came from directors like Wu Tianming (The Old Well, The King of Masks) and Zhang Yimou (House of Flying Daggers, Raise the Red Lantern).

Image copyrightNANHAI FILMS

Image copyrightNANHAI FILMSThey were largely preoccupied with themes like the loss of youth, tradition versus change, and creating the rural aesthetic most people associated with Chinese film.

But China in the 1980s was a scene of rapid modernisation, urbanisation and Westernisation, and films started responding to the impact of this massive change.

In Dislocation, a scientist creates an android version of himself to attend the endless meetings that rob him of his time, in a black comedy of mechanisation and bureaucracy.

Huang’s take on the debate on artificial intelligence is superbly delivered against a surreal Kafka-esque dreamscape, with stark lighting and suspenseful music, making this film a delight to watch.

Hopefully the new interest in kehuan will see it gain an official release in the West.

Warrior Revived

Li Guomin, 1995

A grown-up style of kehuan emerged in the 1990s, reflecting the themes of identity versus technological advancement which were also occupying Western sci-fi at the time.

Image copyrightSHANGHAI FILM STUDIOS

Image copyrightSHANGHAI FILM STUDIOSIn Warrior Revived, police officer Song Da Wei dies a gruesome death on duty and ends up in a decade-long coma. He’s brought back to life by a “miracle cure” from a biologist who has found a way to repair defective DNA.

The genetically enhanced Song finds himself uncomfortable with the cyberised world around him, and excluded by his old comrades. Meanwhile, the heavily maimed villain he gave his life to destroy is plotting to steal the gene formula and wreak his revenge.

Like a lot of great cyberpunk movies before the age of CGI, this early mainland kehuan impresses with its high kitsch, low-budget, imaginative approach.

The villain’s lair is filled with neon tubes, hand-crafted lab controls and walls covered with plastic bowls in the best traditions of the Tardis.

What it lacks in sleekness it more than makes up with innovative costume designs and soundtrack, diligent camera work and the sheer energy from the cast.

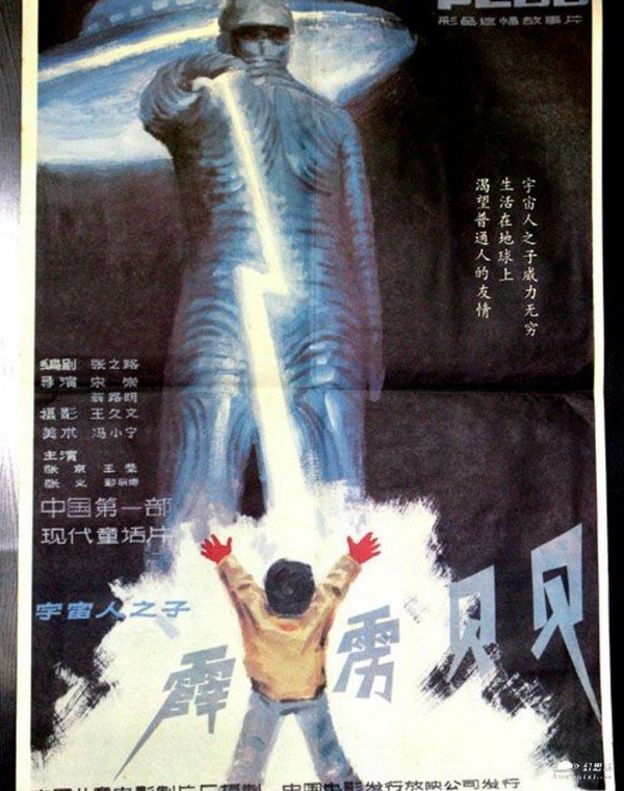

Wonder Boy

Song Chong, 1988

The 1980s brought a slew of Hollywood sci-fi films made for children, but which appealed equally to adults – like Explorers, Flight of The Navigator, and D.A.R.Y.L. – and filmmakers in China were taking a similar route.

Image copyrightCHILDREN’S FILM STUDIO

Image copyrightCHILDREN’S FILM STUDIO

Produced by the Children’s Film Studios and hailed as the nation’s first children’s fantasy film, Wonder Boy tells the story of a child born with the ability to generate electricity.

Bei Bei is bullied by neighbours and kept in isolation by parents who want to protect him, but is still a caring and mischievous little boy, who uses his powers to help others and have fun in equal measure.

When Bei Bei is taken away to be experimented on – by a non-governmental, possibly foreign group – a handful of the close friends he has made come to his rescue.

Well-loved for its humour and accessibility, Wonder Boy is remembered in China as a great classic, and still enjoyed by children today when it is repeated on both national television and streaming services.

Reset

Hong-Seung Yoon, 2017

Produced by Jackie Chan and winner of the 2017 Grand Remi for Best Feature and Best Actress, Reset is a time travel thriller, which addresses a Chinese preoccupation with personal roles in a culture that so totally promotes the good of society.

Xia Tian (Yang Mi) is a senior researcher of wormhole technology and a single mother. When her young son is kidnapped, she is forced to hand over her research, but when the villain murders her child anyway she is forced to test her own discoveries into time travel in order to save his life, and maybe undo her own betrayal of the programme.

Image copyrightBEIJING YAOYING MOVIE DISTRIBUTION CO LTD

Image copyrightBEIJING YAOYING MOVIE DISTRIBUTION CO LTDA female-led space kehuan story that also deals with single parenthood couldn’t be more relevant in a society that is simultaneously beginning a golden space age, and struggling with attitudes to women’s emancipation.

Super Mechs

Cui Junjie, 2018

Wuxia, or kung fu fantasy, is so intrinsic to Chinese pop culture it was almost inevitable that its tropes would be incorporated into Chinese sci-fi.

Image copyrightSEVEN ENTERTAINMENT PICTURES

Image copyrightSEVEN ENTERTAINMENT PICTURES

Produced exclusively for IQiyi, China’s version of Netflix, Super Mechs is set in 2066 in a world where humanity has begun to experience genetic mutations which leave some people with X-Men style super powers.

Global criminal organisations are threatening the order of society and private entities are stepping up to uphold it by developing highly advanced mechanised power suits.

Hero Xiao Qi is an ordinary office clerk enlisted by the Dragon Clan, who reveal to him his latent mutant ice powers, before arming him with a robotic power suit and sending him on a mission. Little does Xiao Qi know that he will be greeted by another mech-suited warrior with fire-based powers who will fight him to a standstill.

The “warriors with opposite powers” trope is a staple of the wuxia genre, but the film falls deeper down the rabbit hole when this deadly opponent is revealed to be Xiao Qi’s long-lost brother.

Add in ancient warring clans, fast-paced action between the sleek computer-generated mechanical fighters and a cheeky sense of humour from our protagonist, and the high budget Huayi Brothers production appeals to fans of superhero, kung fu and toku/tecuo films alike.

The works of stalwart wuxia authors like Jin Yong are steadily being translated into English, so we will certainly see more from this sub-genre reach our screens.

Acknowledging the rich and varied Chinese science fiction tradition does not at all detract from the pride in the success of Wandering Earth.

With China’s growing middle class and increased youth spending power, Chinese filmmakers are increasingly catering for a booming domestic demand for entertainment, and no longer worry as much about making their films palatable for export.

But with more East-West co-productions in the pipeline, like the animated Next Gen which originated from a Chinese web comic, it is certainly a sensible decision for companies like Netflix to bring films from platforms like IQiyi, to an English speaking audience, and that is going to include kehuan.

Western audiences may not immediately “get” some of these films, or may feel that some elements do not flow to their expectations.

But Wandering Earth and the titles above are the product of China’s culture and worldview. And to some extent, it’s what makes them different that will pique interest, fascinate and entertain.

An outsized image of Father Christmas beamed from the window, flanked by a manic array of snowmen, reindeer and present-stuffed stockings. The masseuses greeted customers in Santa hats.

An outsized image of Father Christmas beamed from the window, flanked by a manic array of snowmen, reindeer and present-stuffed stockings. The masseuses greeted customers in Santa hats.