- Documentary puts China’s literary hero into context: there is Dante, there’s Shakespeare, and there’s Du Fu

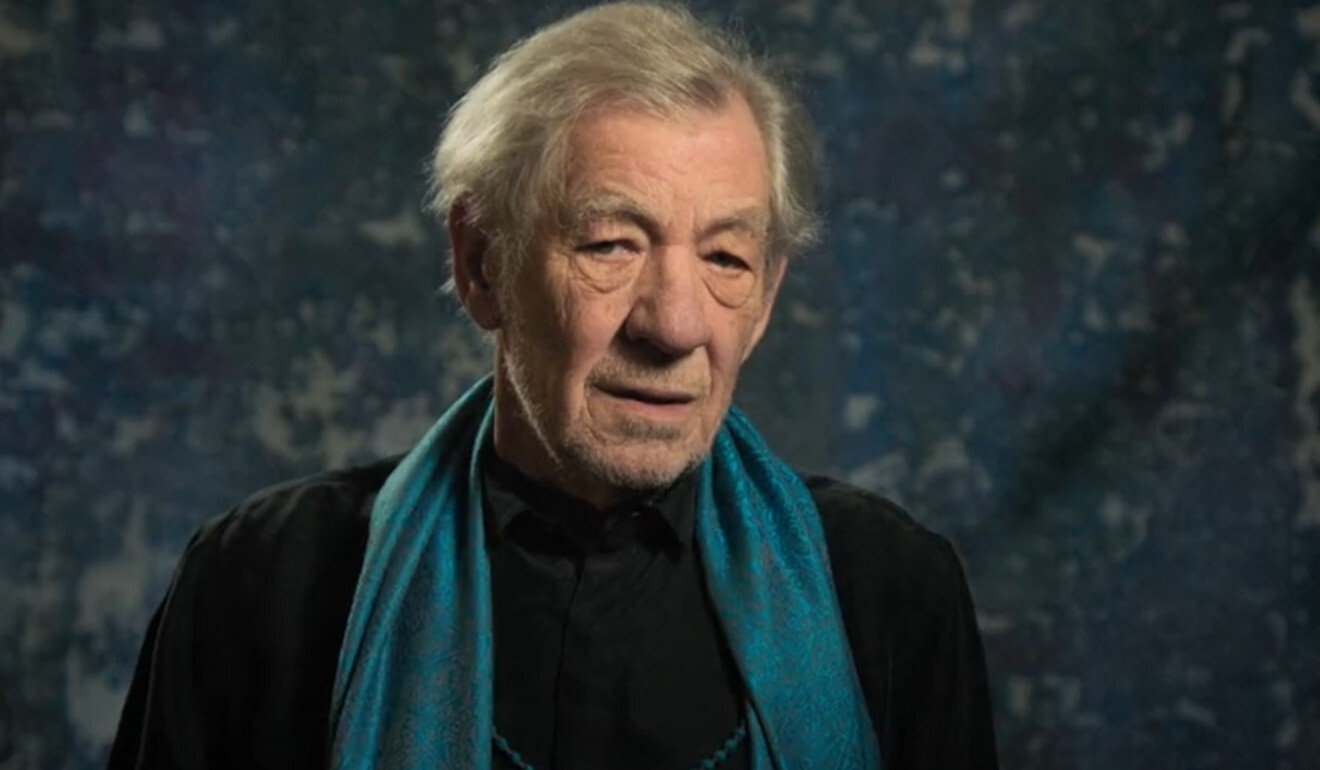

- Theatrical legend Sir Ian McKellen brings glamour to beloved verses in British documentary

“I couldn’t believe it!!” Wood said in an email. “I’m very pleased of course … most of all as a foreigner making a film about such a loved figure in another culture, you hope that the Chinese viewers will think it was worth doing.”

Often referred to as ancient China’s “Sage of Poetry” and the “Poet Historian”, Du Fu witnessed the Tang dynasty’s unparalleled height of prosperity and its fall into rebellion, famine and poverty.

Harvard University sinologist Stephen Owen described the poet’s standing as such: “There is Dante, there’s Shakespeare, and there’s Du Fu.”

The performance of Du’s works by Sir Ian, who enjoyed prominence in China with his role as Gandalf in the Lord of the Rings movie series, attracted popular discussion from both media critics and general audiences in China, and sparked fresh discussion about the poet.

“To a Chinese audience, the biggest surprise could be ‘Gandalf’ reading out the poems! … He recited [Du’s poems] with his deep, stage performance tones in a British accent. No wonder internet users praised it as ‘reciting Du Fu in the form of performing a Shakespeare play,” wrote Su Zhicheng, an editor with National Business Daily.

On Sunday, a writer on the website of the National Supervisory Commission, China’s top anti-corruption agency, claimed – without citing sources – that the Du Fu documentary had moved “anxious” British audience who were still staying home under social distancing measures.

“If anyone wants to put the fear of the coronavirus behind them by understanding the rich Chinese civilisation, please watch this documentary on Du Fu,” it wrote, adding that promoting Du’s poems overseas could help “healing and uniting our shattered world”.

English-language state media such as CGTN and the Global Times reported on the documentary last week and some Beijing-based foreign relations publications have posted comments about the film on Twitter.

Wood said he had received feedback from both Chinese and British viewers that talked about “the need, especially now, of mutual understanding between cultures”.

“It is a global pandemic … we need to understand each other better, to talk to each other, show empathy: and that will help foster cooperation. So even in a small way, any effort to explain ourselves to each other must be a help,” Wood said.

He said the idea for producing a documentary about Du Fu started in 2017, after his team had finished the Story of China series for BBC and PBS.

Du Fu: China’s Greatest Poet first aired in Britain on April 7 on BBC Four, the cultural and documentary channel of the public broadcaster. It is a co-production between the BBC and China Central Television.

Wood said a slightly shorter 50-minute version would be aired later this month on CCTV9, Chinese state television’s documentary channel.

The film was shot in China in September, he said.

“I came back from China [at the] end of September, so we weren’t affected by the Covid-19 outbreak, though of course it has affected us in the editing period. We have had to recut the CCTV version in lockdown here in London and recorded two small word changes on my iPhone!” Wood said.

Source: SCMP