- In 2017 alone, China’s central and local governments allocated US$7.7 billion in subsidies to both carmakers and buyers

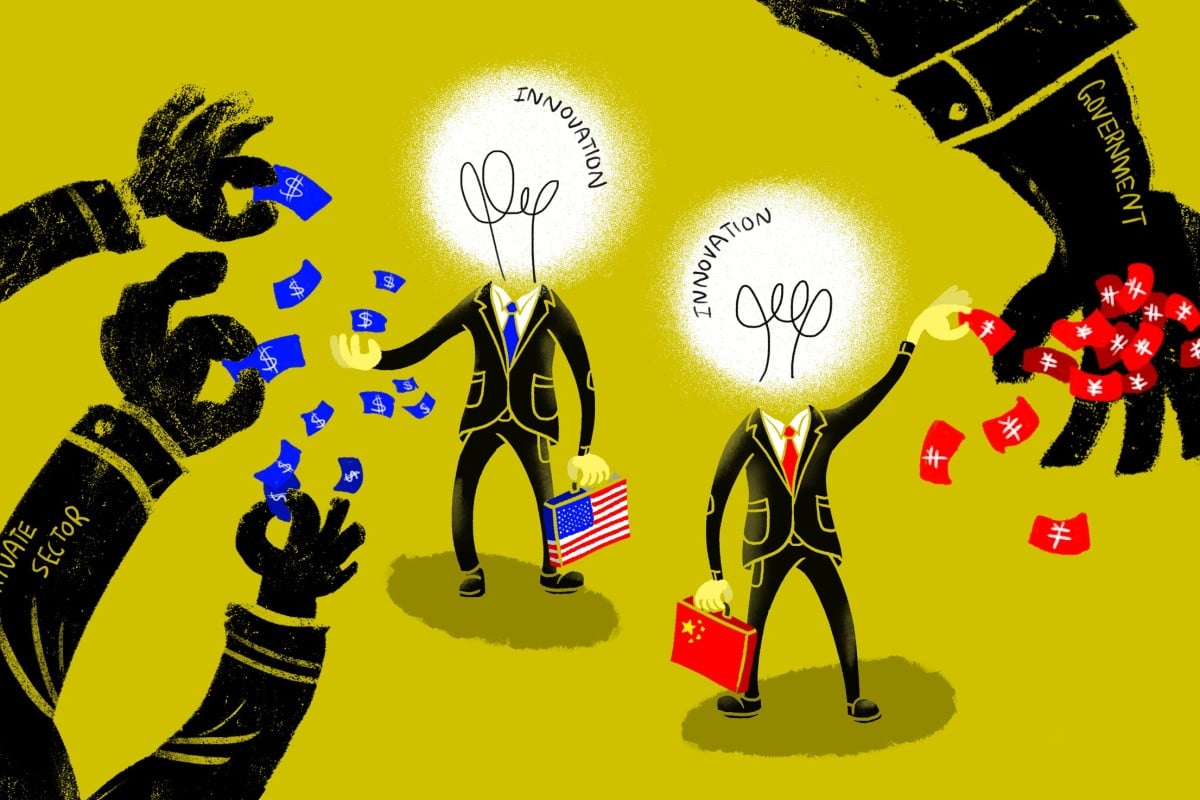

- But how big should the state’s role be in fostering innovation?

It was there that the dean of engineering, Frederick Terman, actively encouraged students to launch companies to exploit these technologies for profit – the most famous of his disciples being Hewlett-Packard founders Bill Hewlett and Dave Packard.

“Most people who came here after the 1980s just assumed it’s all silicon and chips,” said Steve Blank, a Silicon Valley entrepreneur and adjunct professor at Stanford.

“But innovation in Silicon Valley actually started in Stanford University, thanks to a single professor who changed the entire culture.”

After the second world war, Terman, whose background was in electrical engineering, drew upon his wartime experience heading a radio research lab at Harvard to help turn Stanford into a top-tier university specialising in electronic warfare and with government contracts.

“Americans are not smarter than the Chinese. The only thing that holds China back, is that the nature of dissent and creativity are related.”

The region has been lauded for its culture and openness, with countries globally hoping to learn from its success and emulate it by design.

“There’s something special that happens in a city or a region when people are able to pursue new ideas in a very free way,” said Eric Ries, author of the book The Lean Startup.

“When I first came to Silicon Valley, I had a failed start-up on my resume … nobody saw that as a negative, they saw it as a sign that I showed initiative, tried to do something new.

“It’s not that Silicon Valley embraces failure, but it has a different understanding of the likelihood of success of anything new.”

The fact that Silicon Valley also had its beginnings in federal funding suggests that the state has an important role to play when it comes to fostering innovation.

Countries like China, Singapore and Israel have sought to emulate Silicon Valley’s success by designing strategies at a government level to encourage entrepreneurship and innovation.

For China, the need to foster innovation comes at a critical time. The country is caught in an escalating trade and tech war with the US.

As the two nations slap billions in tariffs on each other, the US has also moved to cut off some Chinese technology firms from accessing US technology, with the country’s 5G champion, Huawei Technologies, directly in the firing line.

Why China’s top-down approach can only take tech innovation so far

The Chinese government has now vowed to double down on developing core competencies, including semiconductor manufacturing – a central part of its Made in China 2025 plan which aims to locally produce 70 per cent of the chips the country needs within 10 years.

But Silicon Valley’s history and China’s push in state-led innovation also beg the question: how much of a role does the state play in fostering innovation?

China’s efforts to strengthen its indigenous technology have been ongoing for several decades.

The first big push to boost modern technology capabilities came during the 1980s, putting in place the Torch programme – resulting in Zhongguancun Science Park in Beijing and a variety of other parks across the country.

The period also saw the establishing of the 973 and 863 programmes, which focused on developing basic research and hi-tech R&D, respectively.

The world’s fastest supercomputer, Tianhe-2, and China’s self-developed spacecraft, Shenzhou, were among the fruits of the 863 programme, which was set up in 1988, while 1997’s 973 programme funded research projects in agriculture, energy, material science and other areas.

In 2006, China proposed a 15-year road map for the nation to join the ranks of innovation-oriented countries by the end of 2020. Science and research spending would rise above 2.5 per cent of GDP under the guide to future goals, known as the National Medium to Long-Term Plan for Science and Technology Development.

The master plan identified industries, technologies and research areas such as energy, biotech, human health and diseases that were considered of “utmost importance to the technological advancement of China”.

These goals were elaborated on in three separate five-year plans, the blueprint for China’s social and economic policies, and translated to a string of government efforts in building the infrastructure to support the country’s technology ambitions.

This came in the form of industrial estates and the Thousand Talents plan to nurture and attract talent back to the country, not to mention a wealth of funding that ranged from research grants and subsidies to tax cuts for the private sector and academia.

China’s tech ambitions strengthened under President Xi Jinping, who, on numerous occasions, has called for the construction of an “innovation-driven economy” to make the country a global innovation leader by 2035.

An important initiative under Xi’s leadership was Made in China 2025. First announced in 2015, the programme called for upgrading China’s manufacturing model to better take on the US in strategic industries such as robotics, aerospace and new-energy vehicles.

Can China’s tech industry innovate its way to leadership?

These efforts have boosted some of Beijing’s favoured industries, turning them into rivals of global peers. In 2001, China identified electric vehicles (EV) as a major technology.

Sixteen years later, Shenzhen company BYD has become the world’s biggest EV maker, and a crop of start-ups including WM Motor, Xpeng Motors and the US-listed NIO have joined the race with funding from some of the country’s biggest tech companies and property developers.

In 2017 alone, China’s central and local governments allocated US$7.7 billion in subsidies to both carmakers and the consumers who bought their vehicles, cementing the country’s position as the world’s largest EV market.

Some 770,000 EVs were made and sold in China in 2017, compared with just 199,000 in the US that year.

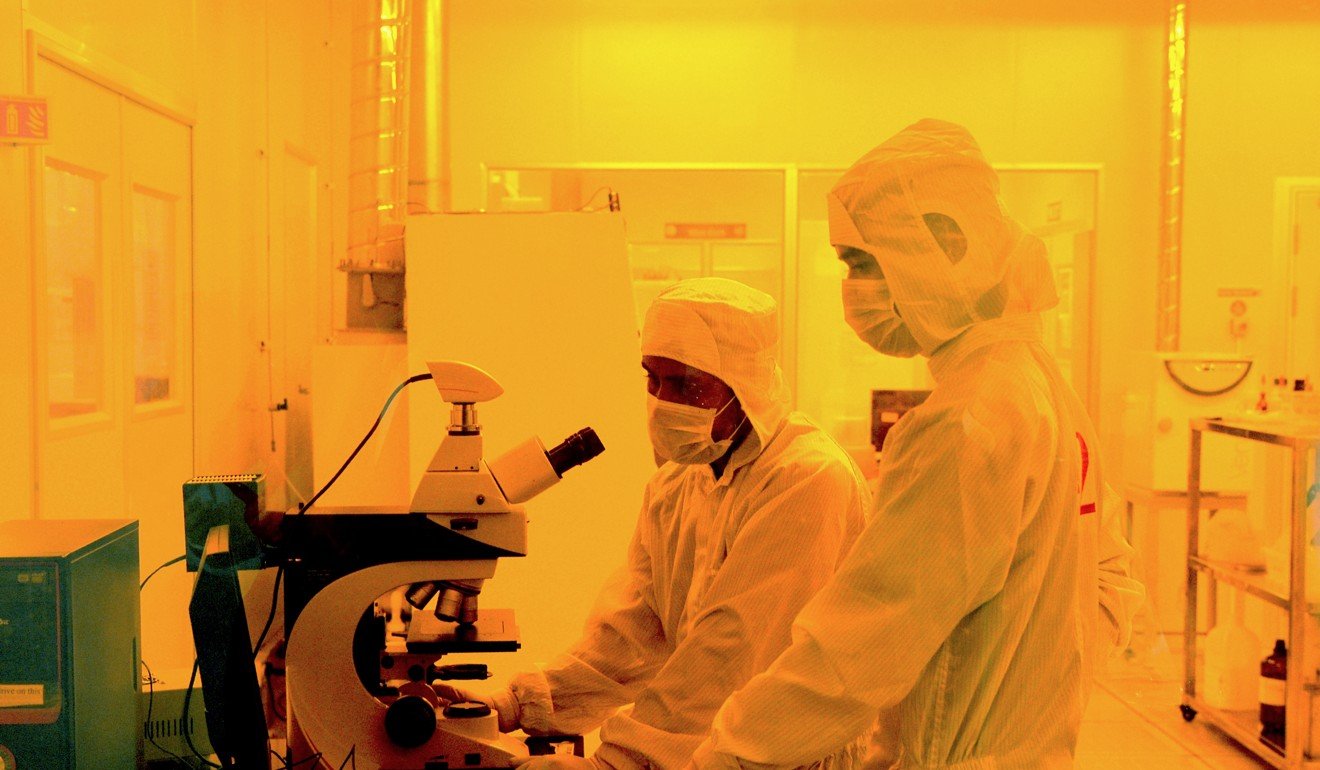

The planning for domestic integrated circuit (IC) production, a strategically important sector identified in the 15-year programme, was further developed in the 12th and 13th five-year plans.

Those concepts grew into an industry involving over 20,000 researchers that aimed to reduce reliance on foreign chip technology, according to China’s Ministry of Science and Technology in 2017.

Yet, as self-reliance is more relevant than ever to China amid the tech war, it still lags behind the US and Taiwan in chip making, despite the billions of dollars in state backing the sector has received.

China’s semiconductor industry needs more than 10 years to catch up with global peers, Jay Huang Jie, founding partner of Jadestone Capital and former Intel managing director in China, said in May.

Some have pointed to China’s tech gap with the US as evidence that the Asian giant does not have what it takes to achieve technological competitiveness.

China, however, is still in the early stages when it comes to developing technology, according to Andy Mok, senior research fellow at the Centre for China and Globalisation, a Beijing-based non-government think tank.

“A lot of research universities in the US – like MIT, Caltech – they’ve had decades of operations [since the second world war and the cold war],” said Mok.

“It’d be quite a myth to say that the US system is so successful technologically because of its political or economic system.”

While semiconductors may not have been a top priority for China until recently, threats of a tech cold war which could cut off the country from US technology, including chips, mean China will double down on developing its own proprietary technology.

In the short term, China could fall further behind the US, Mok said.

Uninspiring Apple shows the US’ best tech days are behind it

“Some of these indigenously produced components were a ‘nice to have’ but not a ‘must-have’ before … it was one priority among many,” Mok said. “Will China’s chips be cutting edge? Probably not, but they will be good enough to be used in the short term.”

But while state-led innovation has helped drive industries, broadly labelling China’s technology achievements as state-driven could be an inaccurate generalisation, said Zhang Jun, dean of the School of Economics at Fudan University and director of the China Centre for Economic Studies, a Shanghai-based think tank.

Some of the more notable innovations in China – like mobile payments – took place on the application level and were driven by private companies such as Alibaba and Tencent.

Alibaba owns the South China Morning Post.

“These companies succeeded by banking on the huge consumer market in China in the internet age,” Zhang said.

Zhang pointed out that while the state did not actively drive those innovations, it too contributed by giving the companies leeway to experiment instead of immediately regulating the industries, which could have stifled innovation.

How the US trade war has accelerated China’s rise

China’s state support comes primarily in basic science and core technology, where it needs to play catch-up with countries like the US, and in the form of investment in universities and research labs that is likely to accelerate due to the trade war with the US.

“Basic scientific research will still rely on the state’s continuous investment into the academic field and into nurturing talents, but in terms of the application of the technology, the government will need to work with the market, and control less,” Zhang said.

Countries that adopt a largely top-down approach to innovation are not uncommon.

In Singapore, a tiny island-nation that lacks natural resources, the Economic Development Board has been instrumental in providing grants and incentives to small business, including low-rent office space for start-ups.

The country also has a nationally-supported artificial intelligence programme called AI Singapore, which is aimed at fostering AI research and talent and bringing private and public sectors closer together when it comes to AI applications.

Israel, which has billed itself as a start-up nation, also has a central agency in charge of planning and executing its innovation policy.

It can also trace its leadership in cybersecurity to the Israel defence forces, whose military intelligence unit 8200 has trained and provided a lot of the manpower for the civilian sector.

Ultimately, despite the role the US and Chinese governments play in driving their respective tech ecosystems, many other factors contribute to the flourishing of an innovation cluster, including private capital and a culture that accepts failure and allows individuals to exercise creativity.

“Getting the state out of the tech ecosystem should be the goal for private capital to take over,” said Stanford’s Blank. “At some point, the government needs to let go.”

Federal funding in the US helped get technology and innovation off the ground in Silicon Valley, but once venture capital started to flow into the region, a culture where innovation was left to the entrepreneurs and tech talent was created.

Blank pointed out that culture also has a big part to play. The US, for example, encourages individualism. Furthermore, in technology hubs like Silicon Valley, Boston and New York, failure is seen as good experience rather than as shameful.

“Americans are not smarter than the Chinese,” said Blank. “The only thing that holds China back, is that the nature of dissent and creativity are related.”

“Great entrepreneurs, great founders are dissidents. Steve Job was a dissident, Elon Musk is a dissident,” he said.

“They tell the status quo, the leadership of whatever industry they’re in that they’re wrong. In the US, that’s in fact part of our culture and we encourage that, but in China you can only do that within the bounds of what the [Communist] Party allows you to do.”

However, Mok disagrees. “Many of the most valuable US companies today are seen as tech leaders because they were able to piggyback on US hegemony,” he said. “If you could win in the US, you could probably win everywhere else.”

Source: SCMP

Leave a comment