Image copyright GETTY IMAGES

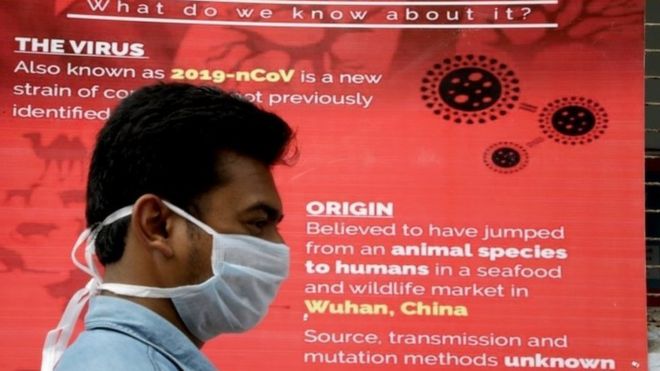

Image copyright GETTY IMAGESIndia is roaring – rather than inching – back to life amid a record spike in Covid-19 infections. The BBC’s Aparna Alluri finds out why.

On Saturday, India’s government announced plans to end a national lockdown that began on 25 March.

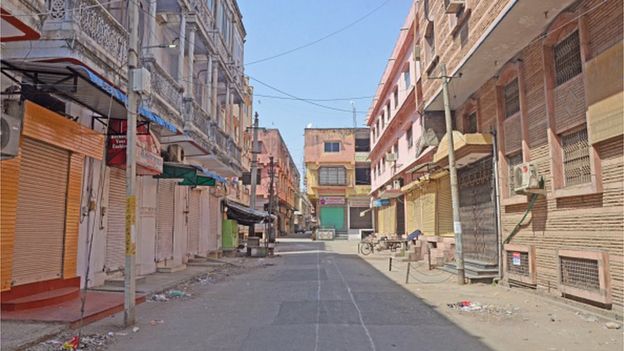

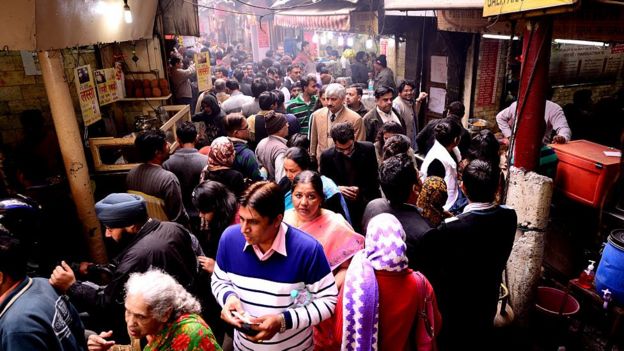

This was expected – the roads, and even the skies, have been busy for the last 10 days since restrictions started to ease for the first time in two months. Many businesses and workplaces are already open, construction has re-started, markets are crowded and parks are filling up. Soon, hotels, restaurants, malls, places of worship, schools and colleges will also reopen.

But the pandemic continues to rage. When India went into lockdown, it had reported 519 confirmed cases and 10 deaths. Now, its case tally has crossed 173,000, with 4,971 deaths. It added nearly 8,000 new cases on Saturday alone – the latest in a slew of record single-day spikes.

Image copyright GETTY IMAGES

Image copyright GETTY IMAGESSo, why the rush to reopen?

The lockdown is simply unaffordable

“It’s certainly time to lift the lockdown,” says Gautam Menon, a professor and researcher on models of infectious diseases.

“Beyond a point, it’s hard to sustain a lockdown that has gone on for so long – economically, socially and psychologically.”

- Will coronavirus lockdown cause food shortages in India?

- The India migrants dying to get home

- How India’s behemoth railways are joining the fight against Covid-19

From day one, India’s lockdown came at a huge cost, especially since so many of its people live on a daily wage or close to it. It put food supply chains at risk, cost millions their livelihood, and throttled every kind of business – from car manufacturers to high-end fashion to the corner shop selling tobacco. As the economy sputtered and unemployment rose, India’s growth forecast tumbled to a 30-year-low.

Raghuram Rajan, an economist and former central bank governor, said at the end of April that the country needed to open up quickly, and any further lockdowns would be “devastating”.

The opinion is shared by global consultant Mckinsey, whose report from earlier this month said India’s economy must be “managed alongside persistent infection risks”.

Image copyright GETTY IMAGES

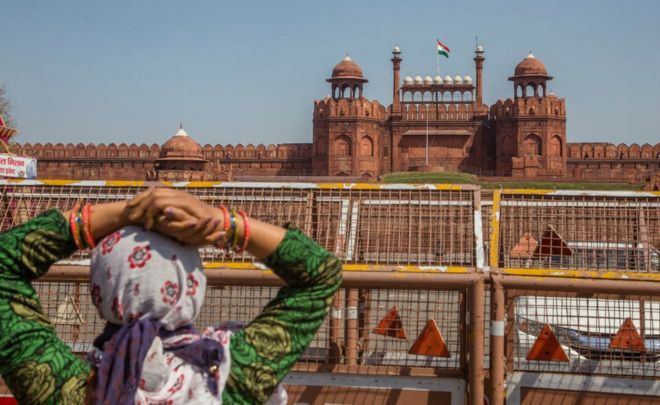

Image copyright GETTY IMAGES“The original purpose of the lockdowns was to delay the spike so we can put health services and systems in place, so we are able handle the spike [when it comes],” says Dr N Devadasan, a public health expert. “That objective, to a large extent, has been met.”

In the last two months, India has turned stadia, schools and even train coaches into quarantine centres, added and expanded Covid-19 wards in hospitals, and ramped up testing as well as production of protective gear. While grave challenges remain and shortages persist, the consensus seems to be that the government has bought as much time as possible.

“We have used the lockdown period to prepare ourselves… Now is the time to revive the economy,” Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal said last week.

The silver lining

For weeks, India’s relatively low Covid-19 numbers baffled experts everywhere. Despite the dense population, disease burden and underfunded public hospitals, there was no deluge of infections or fatalities. Low testing rates explain the former, but not the latter.

In fact, India made global headlines not for its caseload but for its botched handling of the lockdown – millions of informal workers, largely migrants, were left jobless overnight. Scared and unsure, many tried to return home, often desperate enough to walk, cycle or hitchhike across hundreds of kilometres.

Perhaps the choice – between a virus that didn’t appear to be wreaking havoc yet, and a lockdown that certainly was – seemed obvious to the government.

But that is changing quickly as cases shoot up. “I suspect we will keep finding more and more cases, but they will mostly be asymptomatic or will have mild symptoms,” Dr Devadasan says.

The hope – which is also encouraging the government to reopen – is that most of India’s undetected infections are not severe enough to require hospitalisation. And so far, except in Mumbai city, there has been no dearth of hospital beds.

India’s Covid-19 data is spotty and sparse, but what it does have suggests that it hasn’t been as badly hit by the virus as some other countries.

The government, for instance, has been touting India’s mortality rate as a silver lining – at nearly 3%, it’s among the lowest in the world.

But some are unconvinced by that. Dr Jacob John, a prominent virologist, says India has never had, and still doesn’t have, a robust system for recording deaths – in his view, the government is certainly missing Covid-19 deaths because they have no way of knowing of every fatality.

Image copyright GETTY IMAGES

Image copyright GETTY IMAGESAnd, he says, “what we must aim for is flattening the mortality curve, not necessarily the epidemic curve”.

Dr John, like several other experts, also predicts a peak in July or August, and believes the country is reopening so quickly because the “government realised the futility of such leaky lockdowns”.

A shift in strategy

So is the government gearing up for another lockdown when the peak comes?

While Dr Menon believes the lockdown was well-timed, he says it was too focused on cases coming from abroad.

“There was a hope that by controlling that, we could prevent epidemic spread, but how effective was our screening [at airports]?”

Now, he adds, is the time for “localised lockdowns”.

The federal government has left it to states to decide where, how and to what extent to lift the lockdown as the virus’ progression varies wildly across India.

Maharashtra alone accounts for more than a third of India’s active cases. Add Tamil Nadu, Gujarat and Delhi, and that makes up 67% of the national total.

But other states – such as Bihar – are already seeing a sharp uptick as migrant workers return home.

“Initially, most of your cases were in the cities,” Dr Devadasan says. “But we kept the migrant workers in cities and didn’t allow them to go home. Now, we are sending them back. We have facilitated transporting the virus from urban areas to rural areas.”

While the government has said how many infections have been avoided – up to 300,000 – and lives saved – up to 71,000 – by the lockdown, there is no indication of what lies ahead.

There is only advice: The day the government began to ease restrictions, Mr Kejriwal tweeted, urging people to “follow discipline and control the coronavirus disease” as it was their “responsibility”.

Image copyright GETTY IMAGES

Image copyright GETTY IMAGESBecause the alternative – of curfews and constant policing – is unsustainable.

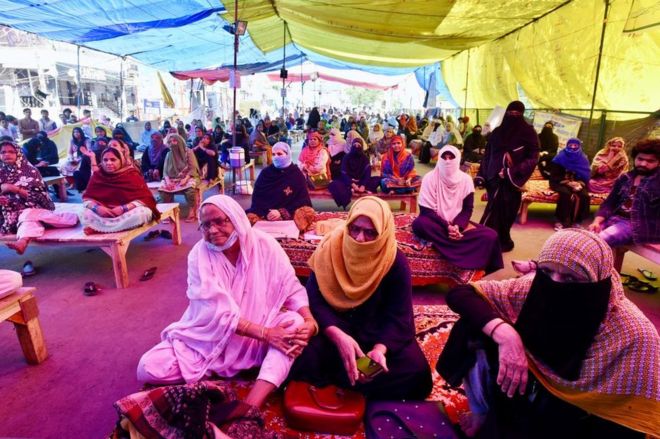

“My worry is more the circumstances of people – it’s not as though they have an option to practise social distancing,” Dr Menon says.

And they don’t – not in joint family homes or one-room hovels packed together in slums, not in crowded markets or busy streets where jostling is second nature, or in temples, mosques, weddings or religious processions where more is always merrier.

The overwhelming message is that the virus is here to stay, and we have to learn to live with it – and the only way to do that, it appears, is to let people live with it.

Source: The BBC