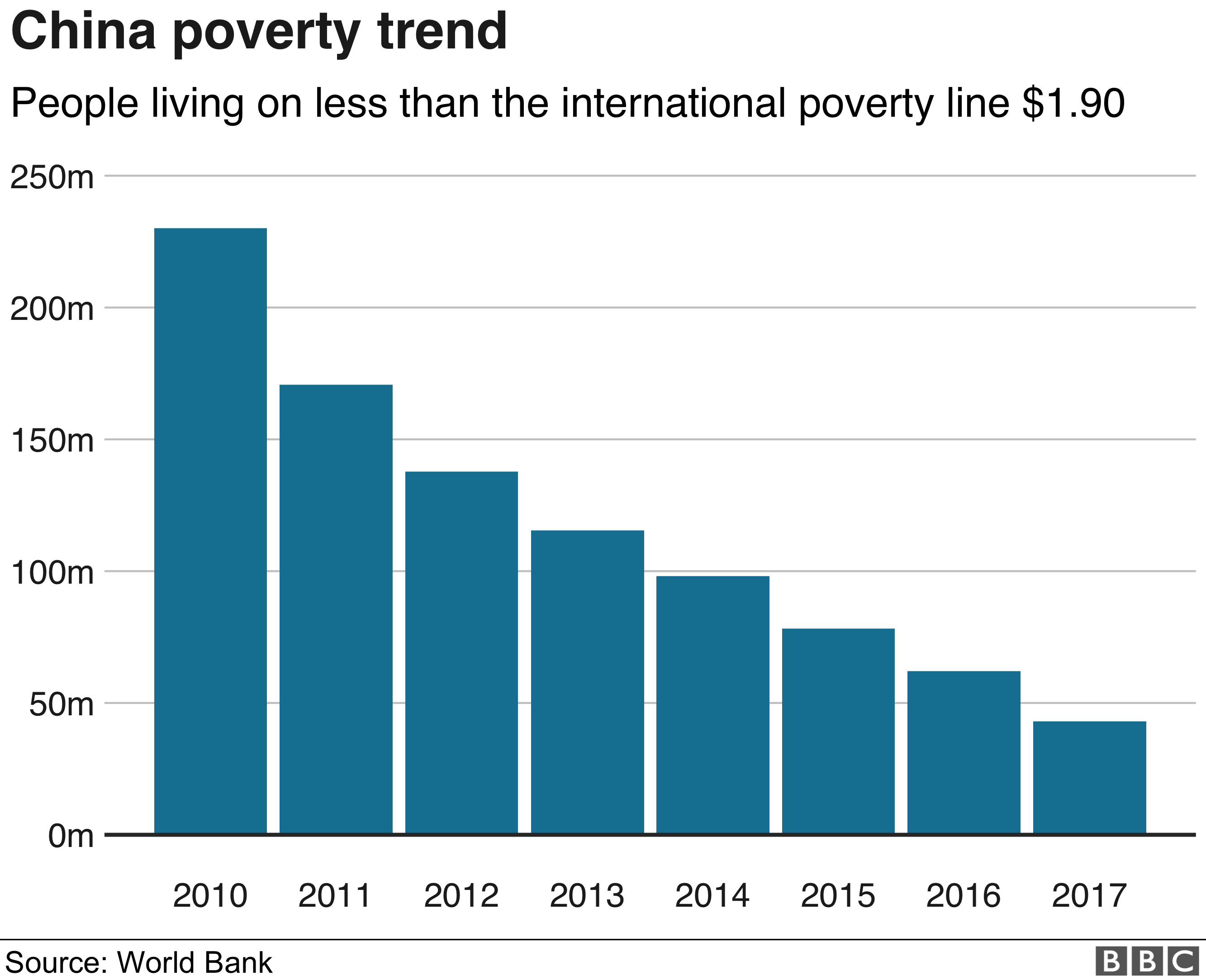

EARLY in the summer Xi Jinping, China’s president, toured one of the country’s poorest provinces, Ningxia in the west. “No region or ethnic group can be left behind,” he insisted, echoing an egalitarian view to which the Communist Party claims to be wedded.

In the 1990s, as China’s economy boomed, inland provinces such as Ningxia fell far behind the prosperous coast, but Mr Xi said there had since been a “gradual reversal” of this trend. He failed to mention that this is no longer happening. As China’s economy slows, convergence between rich and poor provinces is stalling. One of the party’s much-vaunted goals for the country’s development, “common prosperity”, is looking far harder to attain.

This matters to Mr Xi (pictured, in Ningxia). In recent years the party’s leaders have placed considerable emphasis on the need to narrow regional income gaps. They say China will be a “moderately prosperous society” by the end of the decade. It will only be partly so if growth fails to pick up again inland. Debate has started to emerge in China about whether the party has been using the right methods to bring prosperity to backward provinces.

China is very unequal. Shanghai, which is counted as a province, is five times wealthier than the poorest one, Gansu, which has a similar-sized population (see map). That is a wider spread than in notoriously unequal Brazil, where the richest state, São Paulo, is four times richer than the poorest, Piauí (these comparisons exclude the special cases of Hong Kong and Brasília).

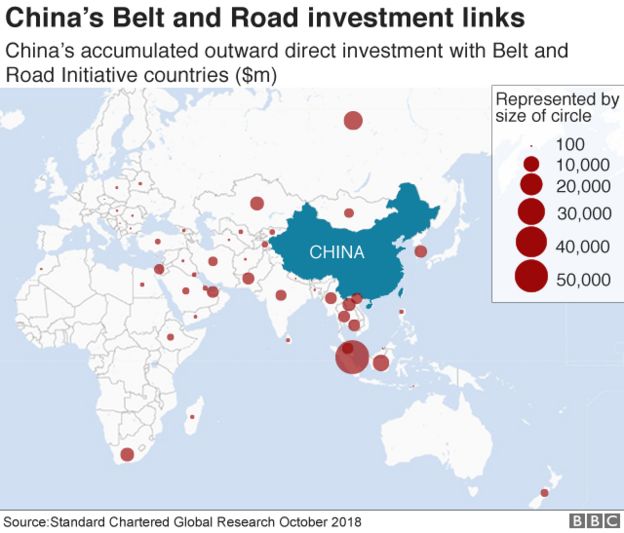

To iron out living standards, the government has used numerous strategies. They include a “Go West” plan involving the building of roads, railways, pipelines and other investment inland; Mr Xi’s signature “Belt and Road” policy aimed partly at boosting economic ties with Central Asia and South-East Asia and thereby stimulating the economies of provinces adjoining those areas; a twinning arrangement whereby provinces and cities in rich coastal areas dole out aid and advice to inland counterparts; and a project to beef up China’s rustbelt provinces in the north-east bordering Russia and North Korea. The central government also gives extra money to poorer provinces. Ten out of China’s 33 provinces get more than half their budgets from the centre’s coffers. Prosperous Guangdong on the coast gets only 10%.

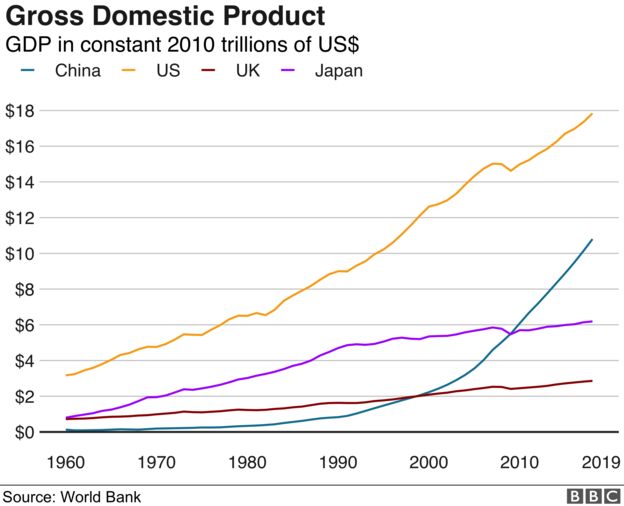

The number, range and cost of these policies suggest the party sees its legitimacy rooted not only in the creation of wealth but the ability to spread it around. Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms, launched in the late 1970s, helped seaboard provinces, which were then poorer than inland ones, to catch up by making things and shipping them abroad. (Mao had discouraged investment in coastal areas, fearing they were vulnerable to attack.) In the 1990s the coast pulled ahead. Then, after 2000, the gap began to narrow again as the worldwide commodity boom—a product of China’s rapid growth—increased demand for raw materials produced in the interior (see chart).

That was a blessing for Mr Xi’s predecessor Hu Jintao, who made “rebalancing” a priority after he became party chief in 2002. It also boosted many economists’ optimism about China’s ability to sustain rapid growth. Even if richer provinces were to slow down, they reckoned, the high growth potential of inland regions would compensate for that.

But convergence is ending. GDP growth slowed across the country last year, but especially in poorer regions. Seven inland provinces had nominal growth below 2%, a recession by Chinese standards (in 2014 only one province reported growth below that level). In contrast, the rich provincial-level municipalities of Shanghai, Beijing and Tianjin, plus a clutch of other coastal provinces including Guangdong, grew between 5% and 8%. Though there were exceptions, the rule of thumb in 2015 was that the poorer the region, the slower the growth. Most of the provinces with below-average growth were poor.

Of course, 2015 was just one year. But a longer period confirms the pattern. Of 31 provinces, 21 had an income below 40,000 yuan ($6,200) per person in 2011. Andrew Batson of Gavekal Dragonomics, a research firm, says that of these 21, 13 (almost two-thirds) saw their real GDP growth slow down by more than 4 points between 2011 and 2014. In contrast, only three of the ten richer provinces (those with income per person above the 40,000 yuan mark) slowed that much. In 2007 all of China’s provinces were narrowing their income gap with Shanghai. In 2015 barely a third of them were. In other words, China’s slowdown has been much sharper in poorer areas than richer ones.

There are three reasons why convergence has stalled. The main one is that the commodity boom is over. Both coal and steel prices fell by two-thirds between 2011 and the end of 2015, before recovering somewhat this year. Commodity-producing provinces have been hammered. Gansu produces 90% of the country’s nickel. Inner Mongolia and Shanxi account for half of coal production. In all but four of the 21 inland provinces, mining and metals account for a higher share of GDP than the national average.

Commodity-influenced slowdowns are often made worse by policy mistakes. This is the second reason for the halt in convergence. Inland provinces built a housing boom on the back of the commodity one, creating what seemed at the time like a perpetual-motion machine: high raw-material prices financed construction which increased demand for raw materials. When commodity prices fell, the boom began to look unsustainable.

The pace of inland growth was evident in dizzying levels of investment in physical assets such as buildings and roads. Between 2008 and last year, as a share of provincial GDP, it rose from 48% to 73% in Shanxi, 64% to 78% in Inner Mongolia, and from 54% to an astonishing 104% in Xinjiang. In the country as a whole, investment as a share of GDP rose only slightly in that period, to 43%. In Shanghai it fell.

This would be fine if the investments were productive, but provinces in the west are notorious for waste. In the coal-rich city of Ordos in Inner Mongolia, on the edge of the Gobi desert, a new district was built, designed for 1m people. It stood empty for years, a symbol of ill-planned extravagance (people are at last moving in).

Investment by the government is keeping some places afloat. Tibet, for example, logged 10.6% growth in the first half of this year, thanks to net fiscal transfers from the central government amounting to a stunning 112% of GDP last year. Given the region’s political significance and strategic location, such handouts will continue—Tibet’s planners admit there is no chance of the region getting by without them for the foreseeable future.

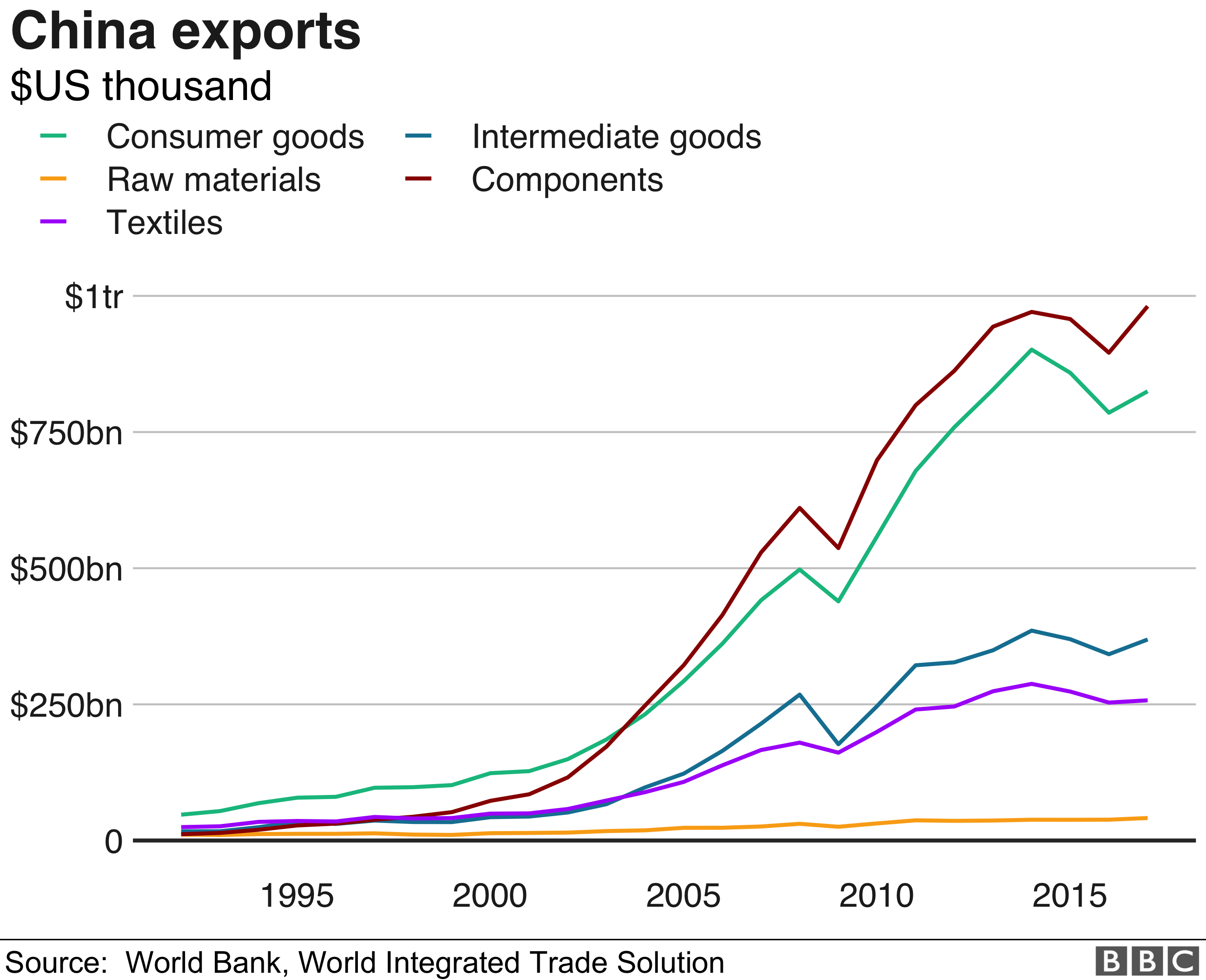

Tibet is an extreme example of the third reason why convergence is ending. Despite oodles of aid, both it and other poor provinces cannot compete with rich coastal ones. In theory, poorer places should eventually converge with rich areas because they will attract businesses with their cheaper labour and land. But it turns out that in China (as elsewhere) these advantages are outweighed by the assets of richer places: better skills and education, more reliable legal institutions, and so-called “network effects”—that is, the clustering of similar businesses in one place, which then benefit from the swapping of ideas and people. A recent study by Ryan Monarch, an economist at America’s Federal Reserve Board, showed that American importers of Chinese goods were very reluctant to change suppliers. When they do, they usually switch to another company in the same city. This makes it hard for inland competitors to break into export markets.

There are exceptions. The south-western region of Chongqing has emerged as the world’s largest exporter of laptops. Chengdu, the capital of neighbouring Sichuan province, is becoming a financial hub. But by and large China’s export industry is not migrating inland. In 2002 six big coastal provinces accounted for 80% of manufactured exports. They still do.

This contrast is worrying. Though income gaps did narrow after 2000 and only stopped doing so recently, provinces have not become alike in other respects. Rich ones continue to depend on world markets and foreign investment. Poor provinces increasingly depend on support from the central government.

A divergence of views

Officials bicker about this. Mr Xi asserted the Robin-Hood view in Ningxia that regional gaps matter and that redistribution is needed. “The first to prosper,” he said, “should help the latecomers.” But three months earlier, an anonymous “authoritative person” (widely believed to be Mr Xi’s own adviser, Liu He) took a more relaxed view, telling the party’s mouthpiece, the People’s Daily, that “divergence is a necessity of economic development,” and “the faster divergence happens, the better.”

It is unclear how this difference will be resolved, though the money must surely be on Mr Xi. Economically, though, Mr Liu is right. Regional-aid programmes have had little impact on the narrowing of income gaps. More of them will not stop those gaps widening. Socially, a slowdown in poorer provinces should not be a problem so long as jobs are still being created in richer ones, enabling migrants from inland to find work there and send money home. But politically the end of convergence is a challenge to Mr Xi, who has been trying to appeal to traditionalists in the party who extol Mao as a champion of equality. Wasteful and ineffective measures to achieve it will remain in place.

Source: Rich province, poor province | The Economist