If China success, it will have proven wrong Matthew 26:11: “The poor will always be with you”.

China is going all out in an unprecedented effort to lift its population out of poverty by 2020, while simultaneously strengthening its grip at the grassroots level.

Xinhua has released the full transcript of President Xi Jinping’s remarks in June on the ambitious campaign. The speech contains many specific details regarding how Xi intends to achieve the goal of meeting the basic needs of all of the country’s rural poor in three years.

The transcript was released on the same day as Beijing’s announcement of the October 18 opening date for the 19th Party Congress. Poverty alleviation is expected to be a policy priority for Xi in his second term.

In the June speech, Xi highlighted the importance of combining the building out of the Communist Party’s grassroots apparatus with poverty alleviation.

“We must send our best talents to the front line of the tough battle with extreme poverty,” Xi told cadres while announcing his precise measures aimed at reducing poverty.

Beijing vows to get tough in war on poverty“All levels of government should actively send cadres to station in poor villages in an effort to fortify the party leadership,” he said.

County governments should take the lead in poverty alleviation, Xi said, adding that having stable leadership at the county level was essential. County leaders who perform well in poverty alleviation should be promoted, he said.Xi said the government should precisely identify its poor and the reasons for their poverty to derive appropriate measures to help them.“

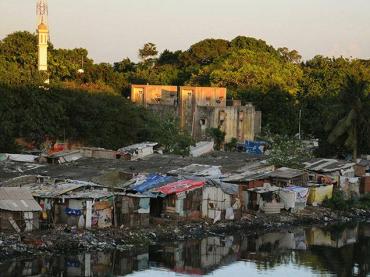

The priority for the next stage is to solve the problems of social services, infrastructure and a basic medical services shortage in areas with deep-rooted poverty issues,” Xi said.

He said the government would step up the campaign to move residents from areas with extremely poor living conditions, hire local people to protect forests in ecologically fragile areas, and strengthen assistance to rural poor who suffer with serious illness.

Xi Jinping’s biggest ally returns to the limelight to support Chinese leader’s war against poverty

Meanwhile, Xi also is prepared to strengthen government funding and prioritise land distribution to meet development needs as part of a basket of precise measures aimed at eradicating extreme poverty.

His programme also includes improving public services such as medical care, education, vocational training, transportation and infrastructure to add jobs and develop industries in some of China’s poorest areas.

Ever since taking the helm, Xi has researched and travelled extensively to extremely poor areas as poverty reduction is a key political target for the Communist Party and the central government. The official goal is to eliminate poverty, defined as annual income of less than 2,300 yuan (HK$2,728), and build an “all-round well-off society” by 2020 with all resources available.

In China, rural rich get richer and poor get poorer

The 13th Five Year Plan has set important targets for the country on this matter and progress in poverty alleviation would play a role in assessing cadres’ performance.

Shanghai-based political commentator Chen Daoyin said poverty alleviation is close to Xi’s heart as it helps the party to solidify its political support in the grassroots where most of the nation’s population lives.

“As his next term begins, one can expect that’s where he will dedicate his power on,” Chen said in an interview.

“Not only it is an easy way out for him to win hearts of the mass but also a way to justify the party’s governance on a grassroots level in order to maintain political stability.

China’s final push to eradicate poverty will be difficult but not impossible if handled in a clean, transparent manner“

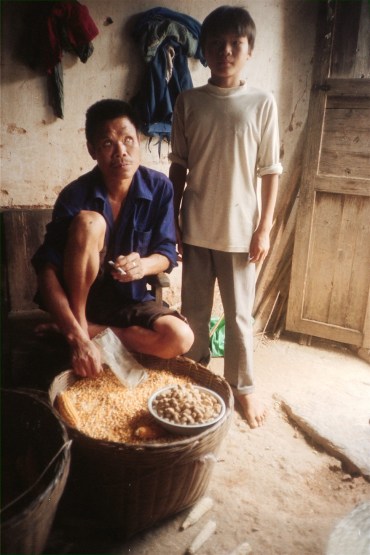

China’s poorest takes up the majority of the population and all their problems are about staying warm and fed, which is easy to address compared to the more affluent bunch on the eastern part of the nation,” Chen said.

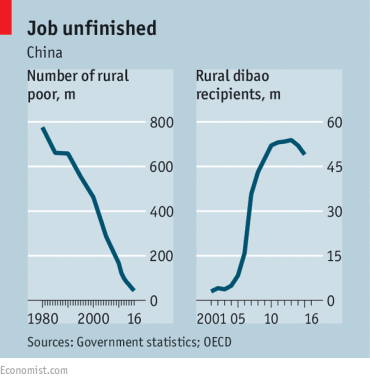

As of last year, China still has more than 55 million people in rural areas who live below the poverty line. Twelve million people were lifted out of poverty last year and another 10 million people would be taken off the rolls this year.