Image copyright UHRP

Image copyright UHRPA document that appears to give the most powerful insight yet into how China determined the fate of hundreds of thousands of Muslims held in a network of internment camps has been seen by the BBC.

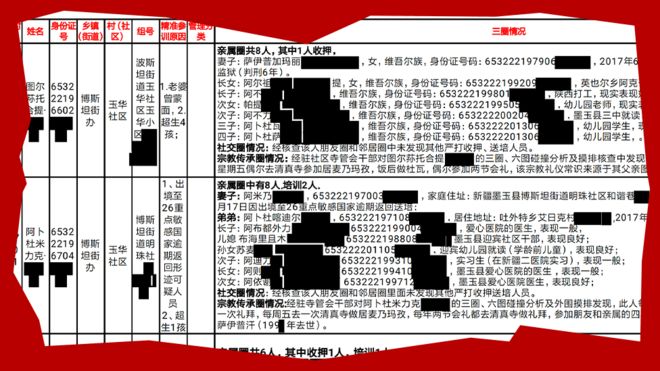

Listing the personal details of more than 3,000 individuals from the far western region of Xinjiang, it sets out in intricate detail the most intimate aspects of their daily lives.

The painstaking records – made up of 137 pages of columns and rows – include how often people pray, how they dress, whom they contact and how their family members behave.

China denies any wrongdoing, saying it is combating terrorism and religious extremism.

The document is said to have come, at considerable personal risk, from the same source inside Xinjiang that leaked a batch of highly sensitive material published last year.

One of the world’s leading experts on China’s policies in Xinjiang, Dr Adrian Zenz, a senior fellow at the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation in Washington, believes the latest leak is genuine.

“This remarkable document presents the strongest evidence I’ve seen to date that Beijing is actively persecuting and punishing normal practices of traditional religious beliefs,” he says.

One of the camps mentioned in it, the “Number Four Training Centre” has been identified by Dr Zenz as among those visited by the BBC as part of a tour organised by the Chinese authorities in May last year.

Much of the evidence uncovered by the BBC team appears to be corroborated by the new document, redacted for publication to protect the privacy of those included in it.

It contains details of the investigations into 311 main individuals, listing their backgrounds, religious habits, and relationships with many hundreds of relatives, neighbours and friends.

Verdicts written in a final column decide whether those already in internment should remain or be released, and whether some of those previously released need to return.

It is evidence that appears to directly contradict China’s claim that the camps are merely schools.

In an article analysing and verifying the document, Dr Zenz argues that it also offers a far deeper understanding of the real purpose of the system.

It allows a glimpse inside the minds of those making the decisions, he says, laying bare the “ideological and administrative micromechanics” of the camps.

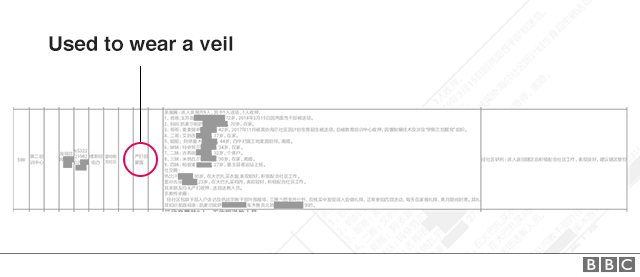

Row 598 contains the case of a 38-year-old woman with the first name Helchem, sent to a re-education camp for one main reason: she was known to have worn a veil some years ago.

It is just one of a number of cases of arbitrary, retrospective punishment.

Others were interned simply for applying for a passport – proof that even the intention to travel abroad is now seen as a sign of radicalisation in Xinjiang.

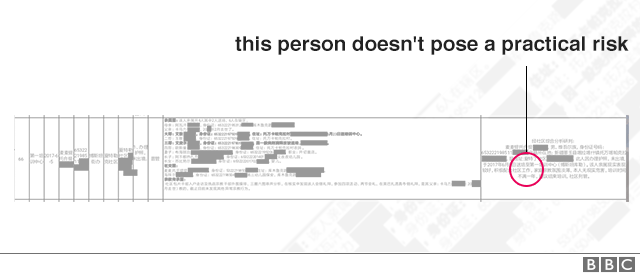

In row 66, a 34-year-old man with the first name Memettohti was interned for precisely this reason, despite being described as posing “no practical risk”.

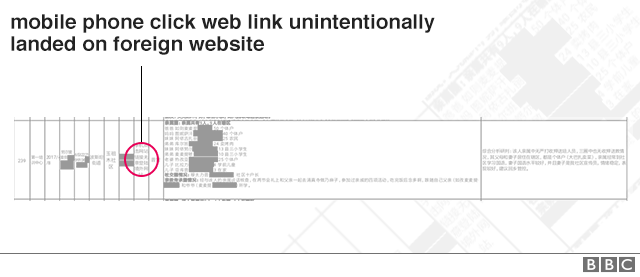

And then there’s the 28-year-old man Nurmemet in row 239, put into re-education for “clicking on a web-link and unintentionally landing on a foreign website”.

Again, his case notes describe no other issues with his behaviour.

The 311 main individuals listed are all from Karakax County, close to the city of Hotan in southern Xinjiang, an area where more than 90% of the population is Uighur.

Predominantly Muslim, the Uighurs are closer in appearance, language and culture to the peoples of Central Asia than to China’s majority ethnicity, the Han Chinese.

In recent decades the influx of millions of Han settlers into Xinjiang has led to rising ethnic tensions and a growing sense of economic exclusion among Uighurs.

Those grievances have sometimes found expression in sporadic outbreaks of violence, fuelling a cycle of increasingly harsh security responses from Beijing.

It is for this reason that the Uighurs have become the target – along with Xinjiang’s other Muslim minorities, like the Kazakhs and Kyrgyz – of the campaign of internment

The “Karakax List”, as Dr Zenz calls the document, encapsulates the way the Chinese state now views almost any expression of religious belief as a signal of disloyalty.

To root out that perceived disloyalty, he says, the state has had to find ways to penetrate deep into Uighur homes and hearts.

In early 2017, when the internment campaign began in earnest, groups of loyal Communist Party workers, known as “village-based work teams”, began to rake through Uighur society with a massive dragnet.

With each member assigned a number of households, they visited, befriended and took detailed notes about the “religious atmosphere” in the homes; for example, how many Korans they had or whether religious rites were observed.

The Karakax List appears to be the most substantial evidence of the way this detailed information gathering has been used to sweep people into the camps.

It reveals, for example, how China has used the concept of “guilt by association” to incriminate and detain whole extended family networks in Xinjiang.

For every main individual, the 11th column of the spreadsheet is used to record their family relationships and their social circle.

China’s hidden camps

- The long read: China’s hidden camps

- Explainer: China’s Muslim ‘crackdown’

- Searching for truth in China’s ‘re-education’ camps

- China denies Muslim children separation campaign

Alongside each relative or friend listed is a note of their own background; how often they pray, whether they’ve been interned, whether they’ve been abroad.

In fact, the title of the document makes clear that the main individuals listed all have a relative currently living overseas – a category long seen as a key indicator of potential disloyalty, leading to almost certain internment.

Rows 179, 315 and 345 contain a series of assessments for a 65-year-old man, Yusup.

His record shows two daughters who “wore veils and burkas in 2014 and 2015”, a son with Islamic political leanings and a family that displays “obvious anti-Han sentiment”.

His verdict is “continued training” – one of a number of examples of someone interned not just for their own actions and beliefs, but for those of their family.

The information collected by the village teams is also fed into Xinjiang’s big data system, called the Integrated Joint Operations Platform (IJOP).

The IJOP contains the region’s surveillance and policing records, culled from a vast network of cameras and the intrusive mobile spyware every citizen is forced to download.

The IJOP, Dr Zenz suggests, can in turn use its AI brain to cross-reference these layers of data and send “push notifications” to the village teams to investigate a particular individual.

The man found “unintentionally landing on a foreign website” may well have been interned thanks to the IJOP.

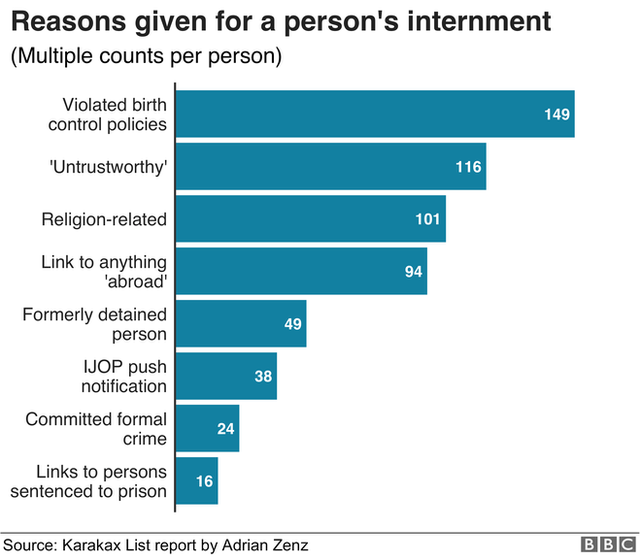

In many cases though, there is little need for advanced technology, with the vast and vague catch-all term “untrustworthy” appearing multiple times in the document.

It is listed as the sole reason for the internment of a total of 88 individuals.

The concept, Dr Zenz argues, is proof that the system is designed not for those who have committed a crime, but for an entire demographic viewed as potentially suspicious.

China says Xinjiang has policies that “respect and ensure people’s freedom of religious belief”. It also insists that what it calls a “vocational training programme in Xinjiang” is “for the purposes of combating terrorism and religious extremism”, adding only people who have been convicted of crimes involving terrorism or religious extremism are being “educated” in these centres.

However, many of the cases in the Karakax List give multiple reasons for internment; various combinations of religion, passport, family, contacts overseas or simply being untrustworthy.

The most frequently listed is for violating China’s strict family planning laws.

In the eyes of the Chinese authorities it seems, having too many children is the clearest sign that Uighurs put their loyalty to culture and tradition above obedience to the secular state.

The Karakax List does contain some references to those kinds of crimes, with at least six entries for preparing, practicing or instigating terrorism and two cases of watching illegal videos.

But the broader focus of those compiling the document appears to be faith itself, with more than 100 entries describing the “religious atmosphere” at home.

The Karakax List has no stamps or other authenticating marks so, at face value, it is difficult to verify.

It is thought to have been passed out of Xinjiang sometime before late June last year, along with a number of other sensitive papers.

They ended up in the hands of an anonymous Uighur exile who passed all of them on, except for this one document.

Only after the first batch was published last year was the Karakax List then forwarded to his conduit, another Uighur living in Amsterdam, Asiye Abdulaheb.

She told the BBC that she is certain it is genuine.

“Regardless of whether there are official stamps on the document or not, this is information about real, live people,” she says. “It is private information about people that wouldn’t be made public. So there is no way for the Chinese government to claim it is fake.”

Like all Uighurs living overseas, Ms Abdulaheb lost contact with her family in Xinjiang when the internment campaign began, and she’s been unable to contact them since.

But she says she had no choice but to release the document, passing it to a group of international media organisations, including the BBC.

“Of course I am worried about the safety of my relatives and friends,” she says. “But if everyone keeps silent because they want to protect themselves and their families, then we will never prevent these crimes being committed.”

At the end of last year China announced that everyone in its “vocational training centres” had now “graduated”. However, it also suggested some may stay open for new students on the basis of their “free will”.

Almost 90% of the 311 main individuals in the Karakax List are shown as having already been released or as being due for release on completion of a full year in the camps.

But Dr Zenz points out that the re-education camps are just one part of a bigger system of internment, much of which remains hidden from the outside world.

More than two dozen individuals are listed as “recommended” for release into “industrial park employment” – career “advice” that they may have little choice but to obey. There are well documented concerns that China is now building a system of coerced labour as the next phase of its plan to align Uighur life with its own vision of a modern society.

In two cases, the re-education ends in the detainees being sent to “strike hard detention”, a reminder that the formal prison system has been cranked into overdrive in recent years.

Many of the family relationships listed in the document show long prison terms for parents or siblings, sometimes for entirely normal religious observances and practices.

One man’s father is shown to have been sentenced to five years for “having a double-coloured thick beard and organising a religious studies group”.

A neighbour is reported to have been given 15 years for “online contact with people overseas”, and another man’s younger brother given 10 years for “storing treasonable pictures on his phone”.

Whether or not China has closed its re-education camps in Xinjiang, Dr Zenz says the Karakax List tells us something important about the psychology of a system that prevails.

“It reveals the witch-hunt-like mindset that has been and continues to dominate social life in the region,” he said.

Source: The BBC