India has said it will ensure the “complete isolation” of Pakistan after a suicide bomber killed 46 soldiers in Indian-administered Kashmir.

Federal Minister Arun Jaitley said India would take “all possible diplomatic steps” to cut Pakistan off from the international community.

India accuses Pakistan of failing to act against the militant group which said it carried out the attack.

This is the deadliest attack to hit the disputed region in decades.

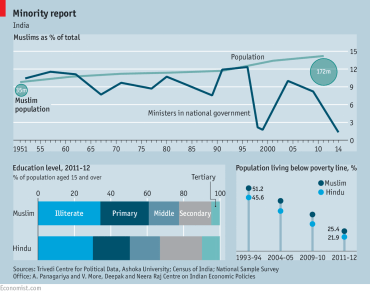

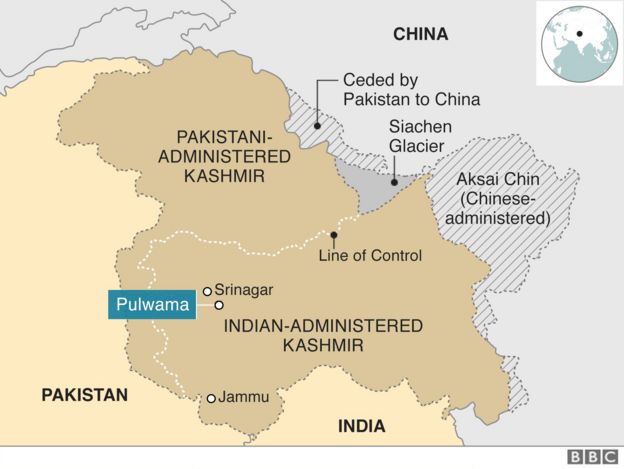

Both India and Pakistan claim all of Muslim-majority Kashmir but only control parts of it.

An insurgency has been ongoing in Indian-administered Kashmir since the late 1980s and there has been an uptick in violence in recent years.

How will India ‘punish’ Pakistan?

India says that Jaish-e-Mohammad, the group behind the attack, has long had sanctuary in Pakistan and accuses its neighbour of failing to crack down on it.

It has called for global sanctions against the group and has said it wants its leader, Masood Azhar, to be listed as a terrorist by the UN security council.

Although India has tried to do this several times in the past, its attempts were repeatedly blocked by China, an ally of Pakistan.

Mr Jaitley set out India’s determination to hold Pakistan to account when speaking to reporters after attending a security meeting early on Friday.

He also confirmed that India would revoke Most Favoured Nation status from Pakistan, a special trading privilege granted in 1996.

Pakistan said it was gravely concerned by the bombing but rejected allegations that it was in any way responsible.

But after Prime Minister Narendra Modi said in a speech that those behind the attack would pay a “heavy price”, many analysts expect more action from Delhi.

After a 2016 attack on an Indian army base that killed 19 soldiers, Delhi said it carried out a campaign of “surgical strikes” in Pakistan-administered Kashmir, across the de facto border. But a BBC investigation found little evidence militants had been hit.

However analysts say that even if the Indian government wants to go further this time, at the moment its options appear limited due to heavy snow across the region.

How did the attack unfold?

The bomber used a vehicle packed with explosives to ram into a convoy of 78 buses carrying Indian security forces on the heavily guarded Srinagar-Jammu highway about 20km (12 miles) from the capital, Srinagar.

“A car overtook the convoy and rammed into a bus,” a senior police official told BBC Urdu.

It stands as the deadliest militant attack on Indian forces in Kashmir since the insurgency began in 1989.

The bomber is reported to be Adil Dar, a high school dropout who left home in March 2018. He is believed to be between the ages of 19 and 21.

Soon after the attack Jaish-e-Mohammad released a video, which was then aired on the India Today TV channel. In it, a young man identified as Adil Dar spoke about what he described as atrocities against Kashmiri Muslims. He said he joined the banned group in 2018 and was eventually “assigned” the task of carrying out the attack in Pulwama.

He also said that by the time the video was released he would be in jannat (heaven).

Dar is one of many young Kashmiri men who have been radicalised in recent years. On Thursday, main opposition leader Rahul Gandhi said that the number of Kashmiri men joining militancy had risen from 88 in 2016 to 191 in 2018.

India has been accused of using brutal tactics to put down protests in Kashmir – with thousands of people sustaining eye injuries from pellet guns used by security forces.

What’s the reaction?

“We will give a befitting reply, our neighbour will not be allowed to de-stabilise us,” said Prime Minister Modi.

Mr Gandhi and two former Indian chief ministers of Jammu and Kashmir all condemned the attack and expressed their condolences.

The attack has also been widely condemned around the world, including by the US and the UN Secretary General.

The White House called on Pakistan to “end immediately the support and safe haven provided to all terrorist groups operating on its soil”.

Pakistan said it strongly rejected any attempts “to link the attack to Pakistan without investigations”.

What’s the background?

There have been at least 10 suicide attacks since 1989 but this is only the second suicide attack to use a car.

Prior to Thursday’s bombing, the deadliest attack on Indian security forces in Kashmir this century came in 2002, when militants killed at least 31 people at an army base in Kaluchak near Jammu, most of them civilians and relatives of soldiers.

At least 19 Indian soldiers were killed when militants stormed a base in Uri in 2016. Delhi blamed that attack on the Pakistani state, which denied any involvement.

The latest attack also follows a spike in violence in Kashmir that came about after Indian forces killed a popular militant, 22-year-old Burhan Wani, in 2016.

More than 500 people were killed in 2018 – including civilians, security forces and militants – the highest such toll in a decade.

- Viewpoint: Will Pakistan mend its ways on terror?

- Pathankot attack: Pakistan arrests Jaish-e-Mohammad militants

India and Pakistan have fought three wars and a limited conflict since independence from Britain in 1947 – all but one were over Kashmir.

Who are Jaish-e-Mohammad?

Started by cleric Masood Azhar in 2000, the group has been blamed for attacks on Indian soil in the past, including one in 2001 on the parliament in Delhi which took India and Pakistan to the brink of war.

Most recently, the group was blamed for attacking an Indian air force base in 2016 near the border in Punjab state. Seven Indian security personnel and six militants were killed.

It has been designated a “terrorist” organisation by India, the UK, US and UN and has been banned in Pakistan since 2002.

However Masood Azhar remains at large and is reportedly based in the Bahawalpur area in Pakistan’s Punjab province.

India has demanded his extradition from Pakistan but Islamabad has refused, citing a lack of proof.

Source: The BBC