Image copyright AFP

Image copyright AFPA Google search for basic information on India’s caste system lists many sites that, with varying degrees of emphasis, outline three popular tropes on the phenomenon.

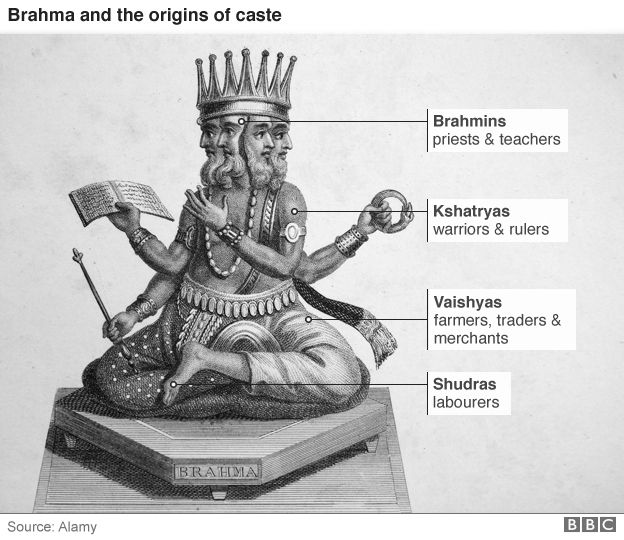

First, the caste system is a four-fold categorical hierarchy of the Hindu religion – with Brahmins (priests/teachers) on top, followed, in order, by Kshatriyas (rulers/warriors), Vaishyas (farmers/traders/merchants), and Shudras (labourers). In addition, there is a fifth group of “Outcastes” (people who do unclean work and are outside the four-fold system).

Second, this system is ordained by Hinduism’s sacred texts (notably the supposed source of Hindu law, the Manusmriti), it is thousands of years old, and it governed all key aspects of life, including marriage, occupation and location.

Third, caste-based discrimination is illegal now and there are policies instead for caste-based affirmative action (or positive discrimination).

These ideas, even seen in a BBC explainer, represent the conventional wisdom. The problem is that the conventional wisdom has not been updated with critical scholarly findings.

- Caste hatred in India – what it looks like

- The Indian Dalit man killed for eating in front of upper-caste men

The first two statements may as well have been written 200 years ago, at the beginning of the 19th Century, which is when these “facts” about Indian society were being made up by the British colonial authorities.

In a new book, The Truth About Us: The Politics of Information from Manu to Modi, I show how the social categories of religion and caste as they are perceived in modern-day India were developed during the British colonial rule, at a time when information was scarce and the coloniser’s power over information was absolute.

This was done initially in the early 19th Century by elevating selected and convenient Brahman-Sanskrit texts like the Manusmriti to canonical status; the supposed origin of caste in the Rig Veda (most ancient religious text) was most likely added retroactively, after it was translated to English decades later.

These categories were institutionalised in the mid to late 19th Century through the census. These were acts of convenience and simplification.

The colonisers established the acceptable list of indigenous religions in India – Hinduism, Sikhism, Jainism – and their boundaries and laws through “reading” what they claimed were India’s definitive texts.

The so-called four-fold hierarchy was also derived from the same Brahman texts. This system of categorisation was also textual or theoretical; it existed only in scrolls and had no relationship with the reality on the ground.

This became embarrassingly obvious from the first censuses in the late 1860s. The plan then was to fit all of the “Hindu” population into these four categories. But the bewildering variety of responses on caste identity from the population became impossible to fit neatly into colonial or Brahman theory.

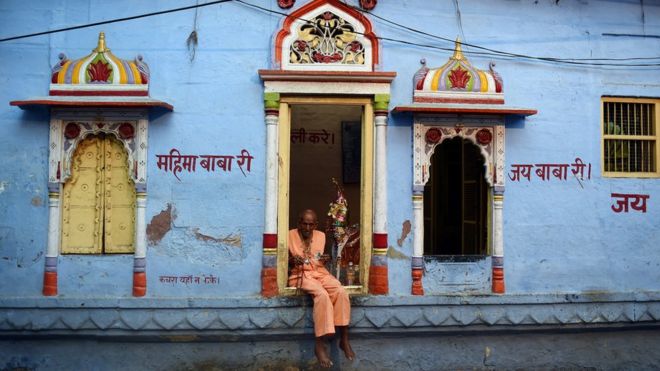

Image copyright GETTY IMAGES

Image copyright GETTY IMAGESWR Cornish, who supervised census operations in the Madras Presidency in 1871, wrote that “… regarding the origin of caste we can place no reliance upon the statements made in the Hindu sacred writings. Whether there was ever a period in which the Hindus were composed of four classes is exceedingly doubtful”.

Similarly, CF Magrath, leader and author of a monograph on the 1871 Bihar census, wrote, “that the now meaningless division into the four castes alleged to have been made by Manu should be put aside”.

Anthropologist Susan Bayly writes that “until well into the colonial period, much of the subcontinent was still populated by people for whom the formal distinctions of caste were of only limited importance, even in parts of the so-called Hindu heartland… The institutions and beliefs which are now often described as the elements of traditional caste were only just taking shape as recently as the early 18th Century”.

In fact, it is doubtful that caste had much significance or virulence in society before the British made it India’s defining social feature.

Astonishing diversity

The pre-colonial written record in royal court documents and traveller accounts studied by professional historians and philologists like Nicholas Dirks, GS Ghurye, Richard Eaton, David Shulman and Cynthia Talbot show little or no mention of caste.

Social identities were constantly malleable. “Slaves” and “menials” and “merchants” became kings; farmers became soldiers, and soldiers became farmers; one’s social identity could be changed as easily as moving from one village to another; there is little evidence of systematic and widespread caste oppression or mass conversion to Islam as a result of it.

All the available evidence calls for a fundamental re-imagination of social identity in pre-colonial India.

The picture that one should see is of astonishing diversity. What the colonisers did through their reading of the “sacred” texts and the institution of the census was to try to frame all of that diversity through alien categorical systems of religion, race, caste and tribe. The census was used to simplify – categorise and define – what was barely understood by the colonisers using a convenient ideology and absurd (and shifting) methodology.

Image copyright AFP

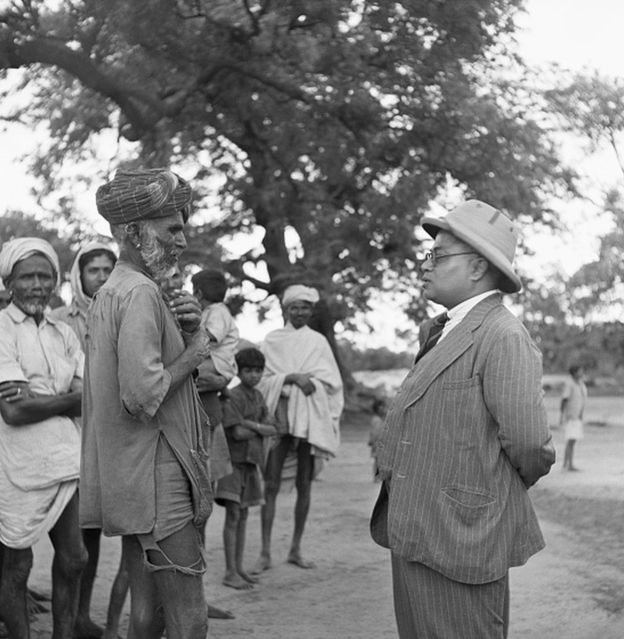

Image copyright AFPThe colonisers invented or constructed Indian social identities using categories of convenience during a period that covered roughly the 19th Century.

This was done to serve the British Indian government’s own interests – primarily to create a single society with a common law that could be easily governed.

A very large, complex and regionally diverse system of faiths and social identities was simplified to a degree that probably has no parallel in world history, entirely new categories and hierarchies were created, incompatible or mismatched parts were stuffed together, new boundaries were created, and flexible boundaries hardened.

Image copyright GETTY IMAGES

Image copyright GETTY IMAGESThe resulting categorical system became rigid during the next century and quarter, as the made-up categories came to be associated with real rights. Religion-based electorates in British India and caste-based reservations in independent India made amorphous categories concrete. There came to be real and material consequences of belonging to one category (like Jain or Scheduled Caste) instead of another. Categorisation, as it turned out in India, was destiny.

The vast scholarship of the last few decades allows us to make a strong case that the British colonisers wrote the first and defining draft of Indian history.

So deeply inscribed is this draft in the public imagination that it is now accepted as the truth. It is imperative that we begin to question these imagined truths.

Source: The BBC