26/09/2019

- An increasing proportion of young people no longer willing to wait tables in China as restaurant owners look to new technology for answers

Catering robots developed by Pudu Tech, the three-year-old Shenzhen start-up, have been adopted by thousands of restaurants in China, as well as some foreign countries including Singapore, Korea, and Germany. Photo: Handout

Two years ago, Bao Xiangyi quit school and worked as a waiter in a restaurant for half a year to support himself, and the 19 year-old remembers the time vividly.

“It was crazy working in some Chinese restaurants. My WeChat steps number sometimes hit 20,000 in a day [just by delivering meals in the restaurant],” said Bao.

The WeChat steps fitness tracking function gauges how many steps you literally take and 20,000 steps per day can be compared with a whole day of outdoor activity, ranking you very high in a typical friends circle.

Bao, now a university student in Hangzhou, Zhejiang province, quit the waiter job and went back to school.

“I couldn’t accept that for 365 days a year every day would be the same,” said Bao.

“Those days were filled with complete darkness and I felt like my whole life would be spent as an inferior and insignificant waiter.”

Olivia Niu, a 23-year-old Hong Kong resident, quit her waiter job on the first day. “It was too busy during peak meal times. I was so hungry myself but I needed to pack meals for customers,” said Niu.

Being a waiter has never been a top career choice but it remains a big source of employment in China. Yang Chunyan, a waitress at the Lanlifang Hotel in Wenzhou in southeastern China, has two children and says she chose the job because she needs to make a living.

Catering robots developed by Pudu Tech, the three-year-old Shenzhen start-up. Photo: Handout

Today’s young generation have their sights on other areas though. Of those born after 2000, 24.5 per cent want careers related to literature and art. This is followed by education and the IT industry in second and third place, according to a recent report by Tencent QQ and China Youth Daily.

Help may now be at hand though for restaurants struggling to find qualified table staff who are able to withstand the daily stress of juggling hundreds of orders of food. The answer comes in the form of robots.

Japan’s industrial robots industry becomes latest victim of the trade war

Shenzhen Pudu Technology, a three-year-old Shenzhen start-up, is among the tech companies offering catering robots to thousands of restaurant owners who are scrambling to try to plug a labour shortfall with new tech such as machines, artificial intelligence and online ordering systems. It has deployed robots in China, Singapore, Korea and Germany.

With Pudu’s robot, kitchen staff can put meals on the robot, enter the table number, and the robot will deliver it to the consumer. While an average human waiter can deliver 200 meals per day – the robots can manage 300 to 400 orders.

“Nearly every restaurant owner [in China] says it’s hard to recruit people to [work as a waiter],” Zhang Tao, the founder and CEO of Pudu tech said in an interview this week. “China’s food market is huge and delivering meals is a process with high demand and frequency.”

Pudu’s robots can be used for ten years and cost between 40,000 yuan (US$5,650) and 50,000 yuan. That’s less than the average yearly salary of restaurant and hotel workers in China’s southern Guangdong province, which is roughly 60,000 yuan, according to a report co-authored by the South China Market of Human Resources and other organisations.

As such, it is no surprise that more restaurants want to use catering robots.

According to research firm Verified Market Research, the global robotics services market was valued at US$11.62 billion in 2018 and is projected to reach US$35.67 billion by 2026.

Haidilao, China’s top hotpot restaurant, has not only adopted service robots but also introduced

a smart restaurant with a mechanised kitchen in Beijing last year. And in China’s tech hub of Shenzhen,

it is hard to pay without an app as most of the restaurants have deployed an online order service.

Can robots and virtual fruit help the elderly get well in China?

China’s labour force advantage has also shrank in recent years. The working-age population, people between 16 and 59 years’ old, has reduced by 40 million since 2012 to 897 million, accounting for 64 per cent of China’s roughly 1.4 billion people in 2018, according to the national bureau of statistics.

By comparison, those of working age accounted for 69 per cent of the total population in 2012.

Other Chinese robotic companies are also entering the market. SIASUN Robot & Automation Co, a hi-tech listed enterprise belonging to the Chinese Academy of Sciences, introduced their catering robots to China’s restaurants in 2017. Delivery robots developed by Shanghai-based Keenon Robotics Co., founded in 2010, are serving people in China and overseas markets such as the US, Italy and Spain.

Pudu projects it will turn a profit this year and it is in talks with venture capital firms to raise a new round of funding, which will be announced as early as October, according to Zhang. Last year it raised 50 million yuan in a round led by Shenzhen-based QC capital.

To be sure, the service industry is still the biggest employer in China, with 359 million workers and accounting for 46.3 per cent of a working population of 776 million people in 2018, according to the national bureau of statistics.

And new technology sometimes offers up new problems – in this case, service with a smile.

“When we go out for dinner, what we want is service. It is not as simple as just delivering meals,” said Wong Kam-Fai, a professor in engineering at the Chinese University of Hong Kong and a national expert appointed by the Chinese Association for Artificial Intelligence. “If they [robot makers] can add an emotional side in future, it might work better.”

Technology companies also face some practical issues like unusual restaurant layouts.

“Having a [catering robot] traffic jam on the way to the kitchen is normal. Some passageways are very narrow with many zigzags,” Zhang said. “But this can be improved in future with more standardised layouts.”

Multi-floor restaurants can also be a problem.

Dai Qi, a sales manager at the Lanlifang Hotel, said it is impossible for her restaurant to adopt the robot. “Our kitchen is on the third floor, and we have boxes on the second, third, and fourth floor. So the robots can’t work [to deliver meals tdownstairs/upstairs],” Dai said.

But Bao says he has no plans to return to being a waiter, so the robots may have the edge.

“Why are human beings doing something robots can do? Let’s do something they [robots] can’t,” Bao said.

Source: SCMP

Posted in ability, answers, Artificial intelligence, artificial intelligence (AI), Beijing, careers, catering robot, China alert, China Youth Daily, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Chinese University of Hong Kong, complain, Consumer, education, foreign countries, founder and CEO, Germany, global robotics services market, guangdong province, Hangzhou, hard to recruit, Hong Kong resident, hundreds of orders, increasing proportion, industrial robots industry, IT industry, Japan, juggle, Korea, labour shortfall, Lanlifang Hotel, latest victim, literature and art, machines, Multi-floor restaurants, national bureau of statistics, National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), new technologies, new technology, online ordering systems, plug, problem, Pudu Tech, restaurant owners, Shanghai, Shenzhen, Shenzhen Pudu Technology, Singapore, smart restaurant, start up, table number, Tech Companies, tencent qq, top hotpot restaurant, trade war, traffic jams, Uncategorized, venture capital firms, Verified Market Research, wait tables, WeChat, Wenzhou, willing, young people, Zhang Tao, zhejiang province, zigzags |

Leave a Comment »

15/09/2019

- An increasing proportion of young people no longer willing to wait tables in China as restaurant owners look to new technology for answers

Catering robots developed by Pudu Tech, the three-year-old Shenzhen start-up, have been adopted by thousands of restaurants in China, as well as some foreign countries including Singapore, Korea, and Germany. Photo: Handout

Two years ago, Bao Xiangyi quit school and worked as a waiter in a restaurant for half a year to support himself, and the 19 year-old remembers the time vividly.

“It was crazy working in some Chinese restaurants. My WeChat steps number sometimes hit 20,000 in a day [just by delivering meals in the restaurant],” said Bao.

The WeChat steps fitness tracking function gauges how many steps you literally take and 20,000 steps per day can be compared with a whole day of outdoor activity, ranking you very high in a typical friends circle.

Bao, now a university student in Hangzhou, Zhejiang province, quit the waiter job and went back to school.

“I couldn’t accept that for 365 days a year every day would be the same,” said Bao. “Those days were filled with complete darkness and I felt like my whole life would be spent as an inferior and insignificant waiter.”

Olivia Niu, a 23-year-old Hong Kong resident, quit her waiter job on the first day. “It was too busy during peak meal times. I was so hungry myself but I needed to pack meals for customers,” said Niu.

Being a waiter has never been a top career choice but it remains a big source of employment in China. Yang Chunyan, a waitress at the Lanlifang Hotel in Wenzhou in southeastern China, has two children and says she chose the job because she needs to make a living.

Catering robots developed by Pudu Tech, the three-year-old Shenzhen start-up. Photo: Handout

Today’s young generation have their sights on other areas though. Of those born after 2000, 24.5 per cent want careers related to literature and art. This is followed by education and the IT industry in second and third place, according to a recent report by Tencent QQ and China Youth Daily.

Help may now be at hand though for restaurants struggling to find qualified table staff who are able to withstand the daily stress of juggling hundreds of orders of food. The answer comes in the form of robots.

Japan’s industrial robots industry becomes latest victim of the trade war

Shenzhen Pudu Technology, a three-year-old Shenzhen start-up, is among the tech companies offering catering robots to thousands of restaurant owners who are scrambling to try to plug a labour shortfall with new tech such as machines, artificial intelligence and online ordering systems. It has deployed robots in China, Singapore, Korea and Germany.

With Pudu’s robot, kitchen staff can put meals on the robot, enter the table number, and the robot will deliver it to the consumer. While an average human waiter can deliver 200 meals per day – the robots can manage 300 to 400 orders.

“Nearly every restaurant owner [in China] says it’s hard to recruit people to [work as a waiter],” Zhang Tao, the founder and CEO of Pudu tech said in an interview this week. “China’s food market is huge and delivering meals is a process with high demand and frequency.”

Pudu’s robots can be used for ten years and cost between 40,000 yuan (US$5,650) and 50,000 yuan. That’s less than the average yearly salary of restaurant and hotel workers in China’s southern Guangdong province, which is roughly 60,000 yuan, according to a report co-authored by the South China Market of Human Resources and other organisations.

As such, it is no surprise that more restaurants want to use catering robots.

According to research firm Verified Market Research, the global robotics services market was valued at US$11.62 billion in 2018 and is projected to reach US$35.67 billion by 2026. Haidilao, China’s top hotpot restaurant, has not only adopted service robots but also introduced a smart restaurant with a mechanised kitchen in Beijing last year. And in China’s tech hub of Shenzhen, it is hard to pay without an app as most of the restaurants have deployed an online order service.

Can robots and virtual fruit help the elderly get well in China?

China’s labour force advantage has also shrank in recent years. The working-age population, people between 16 and 59 years’ old, has reduced by 40 million since 2012 to 897 million, accounting for 64 per cent of China’s roughly 1.4 billion people in 2018, according to the national bureau of statistics.

By comparison, those of working age accounted for 69 per cent of the total population in 2012.

Other Chinese robotic companies are also entering the market. SIASUN Robot & Automation Co, a hi-tech listed enterprise belonging to the Chinese Academy of Sciences, introduced their catering robots to China’s restaurants in 2017. Delivery robots developed by Shanghai-based Keenon Robotics Co., founded in 2010, are serving people in China and overseas markets such as the US, Italy and Spain.

Pudu projects it will turn a profit this year and it is in talks with venture capital firms to raise a new round of funding, which will be announced as early as October, according to Zhang. Last year it raised 50 million yuan in a round led by Shenzhen-based QC capital.

To be sure, the service industry is still the biggest employer in China, with 359 million workers and accounting for 46.3 per cent of a working population of 776 million people in 2018, according to the national bureau of statistics.

And new technology sometimes offers up new problems – in this case, service with a smile.

“When we go out for dinner, what we want is service. It is not as simple as just delivering meals,” said Wong Kam-Fai, a professor in engineering at the Chinese University of Hong Kong and a national expert appointed by the Chinese Association for Artificial Intelligence. “If they [robot makers] can add an emotional side in future, it might work better.”

Technology companies also face some practical issues like unusual restaurant layouts.

“Having a [catering robot] traffic jam on the way to the kitchen is normal. Some passageways are very narrow with many zigzags,” Zhang said. “But this can be improved in future with more standardised layouts.”

Multi-floor restaurants can also be a problem.

Dai Qi, a sales manager at the Lanlifang Hotel, said it is impossible for her restaurant to adopt the robot. “Our kitchen is on the third floor, and we have boxes on the second, third, and fourth floor. So the robots can’t work [to deliver meals to downstairs/upstairs],” Dai said.

But Bao says he has no plans to return to being a waiter, so the robots may have the edge.

“Why are human beings doing something robots can do? Let’s do something they [robots] can’t,” Bao said.

Source: SCMP

Posted in ability, adopted, Art, artificial intelligence (AI), Bao Xiangyi, Beijing, careers, catering robots, CEO of Pudu tech, China alert, China Youth Daily, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Chinese Association for Artificial Intelligence, Chinese University of Hong Kong, complain, darkness, delivering meals, education, foreign countries, Germany, guangdong province, Haidilao, Hangzhou, hotpot restaurant, hundreds of orders, industrial robots industry, IT industry, Italy, Japan, juggle, Keenon Robotics Co, Korea, labour shortfall, Lanlifang Hotel, literature, machines, mechanised kitchen, online ordering systems, plug, Pudu Tech, QC capital, qualified table staff, quit, Restaurant, restaurants, robots, school, Shenzhen, Shenzhen Pudu Technology, SIASUN Robot & Automation Co, Singapore, smart restaurant, South China Market of Human Resources, Spain, start up, tencent qq, trade war, Uncategorized, university student, US, Verified Market Research, victim, waiter, WeChat, Wenzhou, worked, zhejiang province |

Leave a Comment »

05/09/2019

- Doctor who helped 13-year-old girl recover says demands on her to do well at school induced condition

- Weibo poll reveals that 68 per cent of participants had hair loss in school

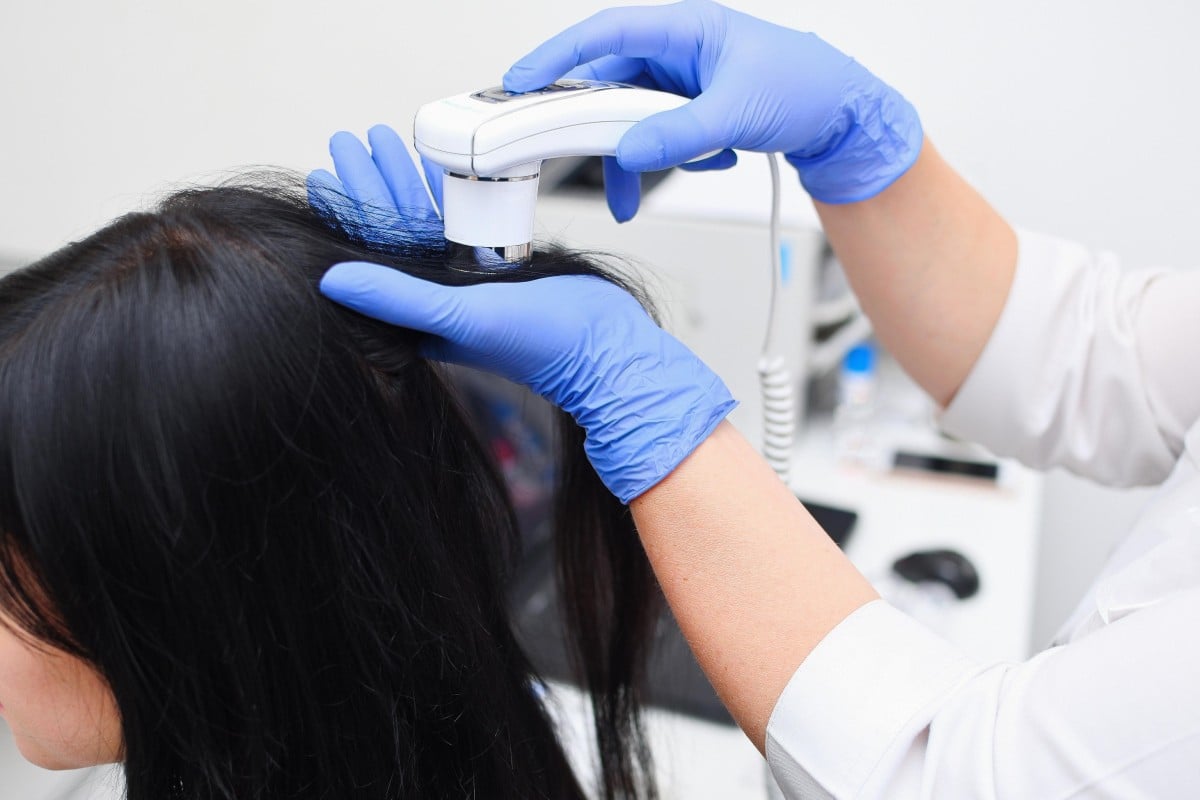

Studies and polls suggest stress leading to hair loss is a big health concern in China. Photo: Alamy

When the 13-year-old girl walked into the hospital in southern China around eight months ago, she was almost completely bald, and her eyebrows and eyelashes had gone.

“The patient came with a hat on and did not look very confident,” Shi Ge, a dermatologist at the Sixth Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University in Guangzhou, told the Pear Video news portal.

The girl had done well in primary school but her grades dropped in middle school, Shi said.

Under parental pressure to do well, the girl pushed herself harder, but the stress resulted in severe hair loss.

With time and medical treatment, the teen’s hair grew back but her story left a lasting impression, raising awareness of the increasing number of young people in China seeking treatment for stress-induced hair loss, according to Chinese media reports.

Jia Lijun, a doctor at Shenzhen Traditional Chinese Medicine Hospital, told state-run Xinhua News Agency in May that aside from genetics, factors such as stress in work, study and life would result in endocrine imbalances which affected the cycle of hair growth.

And in January, a survey of 1,900 people by China Youth Daily found that 64.1 per cent of people aged between 18 and 35 said they had hair loss resulting from long and irregular working hours, insomnia, and mental stress.

Hits and myths: stress and hair loss

Shi said that an increasing number of young people had come to her for treatment of hair loss in recent years, and those working in information technology and white-collar jobs were the two biggest groups.

“They usually could not sleep well at night due to high pressure or had an irregular diet because of frequent business trips,” Shi said.

A Weibo poll on Wednesday revealed that 68 per cent out of 47,000 respondents said they had had serious hair loss when they were in school. About 22 per cent said they noticed after starting their careers, while only 5 per cent said it happened after they entered middle age.

More than half of the Chinese students who took part in a China Youth Daily survey said they had hair loss. Photo Shutterstock

Research published in 2017 by AliHealth, the health and medical unit of the Alibaba Group, found that 36.1 per cent of Chinese people born in the 1990s had hair loss, compared to the 38.5 per cent born in the 1980s. Alibaba is the parent company of the South China Morning Post.

The teenager’s experience sparked a heated discussion on Weibo, with users recounting similar cases and some voicing their panic.

“My niece’s hair was gone while she was in high school and has not recovered, even after she graduated from university. This makes her feel more and more inferior,” one user said.

Hong Kong’s schoolchildren are stressed out – and their parents are making matters worse

Another said: “I lost a small portion of my hair during the high school entrance exam, but that is already scary enough for a girl in her adolescence.”

“I had to quit my job and seek treatment,” said a third, who adding that he also suffered from very serious hair loss a few months ago because of high pressure.

Source: SCMP

Posted in adolescence, Alibaba Group, Alibaba Group Holding, AliHealth, at school, business trips, careers, chasing grades, China Youth Daily, Chinese people, Chinese teenager, condition, debate, demands, dermatologist, do well, doctor, entrance exam, frequent, Guangzhou, hair loss, health and medical unit, her hair, high pressure, High school, induced, inferior, Information technology, irregular diet, job, lost, middle age, middle school, myths, pressure, primary school, quit, recover, school, Shenzhen Traditional Chinese Medicine Hospital, Sixth Affiliated Hospital, south china morning post, sparks, stress, Sun Yat-Sen University, treatment, Uncategorized, university, Weibo, white-collar jobs, Xinhua News Agency, young people |

Leave a Comment »

25/08/2019

- The traditional view that the man of the house must be the breadwinner may be crumbling, according to a recent survey

Just over half of the men questioned said they were in favour of stay-at-home fathers. Photo:Shutterstock

More Chinese husbands are open to the idea of becoming stay-at-home fathers in a shift away from traditional mores, according to a recent survey.

The idea that the man of the house should be the breadwinner, while child care and domestic duties are the woman’s duties, is deep-rooted in Chinese culture.

But the survey, jointly conducted by the state-run China Youth Daily and questionnaire website wenjuan.com earlier this month, found that 52.4 per cent of male respondents supported the idea of men being a full-time carer.

The number in favour was lower among women, just 45.8 per cent of whom supported the idea.

But however keen men may be about the idea, there may also be practical difficulties.

Yu Xiang, a middle schoolteacher in Shanghai who has a six-month-old daughter, said he was willing to be a stay-at-home father but in reality it was not practical to do that because his wife, who is also a teacher, did not earn enough to support the family.

He also said his wife was not happy leaving him to do the housework, adding that she often scolded him for doing it badly. “She also said he would not feel comfortable letting me take care of our daughter,” he said. “She says I am too careless.”

Chinese father decides to drop in on daughter’s school … via helicopter

Robin Ge, a financial manager from Shanghai, admitted he took a more old-fashioned view of household duties.

The father of a five-year-old boy said he would not accept the idea of becoming a stay-at-home father even if his wife, an office worker, started earning more than him.

“Perhaps I am a traditional Chinese man,” he said. “I believe men should earn more than women. I remember my father told me years ago that a man’s status in his family is determined by his economic status. Compared with stay-at-home mothers, the acceptance rate for stay-at-home fathers among the public is very low.

“I agree that a father caring for the kids has benefits, such as helping the kid to be brave and responsible. However, that doesn’t mean a man needs to be full-time father. What he should do is to spend much of his spare time caring for and playing with his kid.”

The survey questioned 1,987 married people, some 89.2 per cent of whom were parents. Sixty per cent of the respondents agreed that the stereotypical view of the husband being the breadwinner put fathers off staying at home to look after the children.

However, the number of women who said they were opposed to the idea of stay-at-home fathers, 30.9 per cent, was slightly higher than the 28 per cent of men who did not support the notion.

But women whose husbands have given up their jobs to look after the children generally appreciated what they had done.

“I don’t think a man who stays at home is a failure in life. His sacrifice helps me so much and I really am grateful for his support,” a woman wrote on China’s leading parental website ci123.com, adding that this kind of family is more stable and the relationship between husband and wife is more harmonious.

Chinese father takes daughter, 10, to top school’s open day despite her being on an IV drip

Zhang Baoyi, a sociology professor at the Tianjin Academy of Social Sciences, said he believed attitudes would change as society evolved.

“To embrace this practice, we need to recognise the contribution and value of homemakers,” Zhang told China Youth Daily.

“The fact that dads are willing to be more involved in their children’s lives shows that the traditional mentality of ‘career husband and domestic wife’ is changing.”

Zhang also said that more parents in general were willing to stay at home to provide full-time child care because they were attaching increasing importance to their children’s education.

“The number of stay-at-home fathers or mothers is increasing,” he said.

“Couples should adjust the [family] model … according to their economic conditions and abilities to educate the children.”

Source: SCMP

Posted in breadwinner, child care and domestic duties, China Youth Daily, Chinese culture, Chinese men, crumbling, economic conditions, housework, man of the house, questionnaire website, schoolteacher, Shanghai, society, sociology professor, stay-at-home fathers, teacher, Tianjin Academy of Social Sciences, traditional view, Uncategorized, wenjuan.com |

Leave a Comment »