Image copyright GETTY IMAGES

Image copyright GETTY IMAGESGlobal retailers are facing scrutiny over cotton supplies sourced from Xinjiang, a Chinese region plagued by allegations of human rights abuses.

China is one of the world’s top cotton producers and most of its crop is grown in Xinjiang.

Rights groups say Xinjiang’s Uighur minority are being persecuted and recruited for forced labour.

Many brands are thought to indirectly source cotton products from the Xinjiang region in China’s far west.

Japanese retailers Muji and Uniqlo attracted attention recently after a report highlighted the brands used the Xinjiang-origin of their cotton as a selling point in advertisements.

H&M, Esprit and Adidas are among the firms said to be at the end of supply chains involving cotton products from Xinjiang, according to a Wall Street Journal investigation.

“You can’t be sure that you don’t have coerced labour in your supply chain if you do cotton business in China,” said Nathan Ruser, researcher at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute.

“Xinjiang labour and what is almost certainly coerced labour is very deeply entrenched into the supply chain that exists in Xinjiang.”

What is happening in Xinjiang?

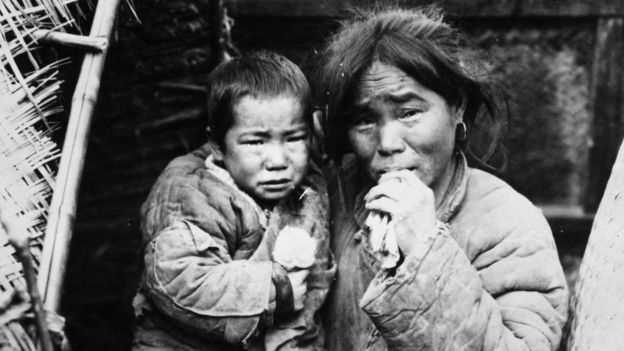

UN experts and human rights groups say China is holding more than a million Uighurs and other ethnic minorities in vast detention camps.

Rights groups also say people in camps are made to learn Mandarin Chinese, swear loyalty to President Xi Jinping, and criticise or renounce their faith.

China says those people are attending “vocational training centres” which are giving them jobs and helping them integrate into Chinese society, in the name of preventing terrorism.

What is produced in Xinjiang?

The Xinjiang region is a key hub of Chinese cotton production.

China produces about 22% of global cotton supplies, according to a report by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS).

Last year, 84% of Chinese cotton came from Xinjiang, the report said.

That has raised concerns over whether forced labour has been used in the production of cotton from the region.

Image copyright GETTY IMAGES

Image copyright GETTY IMAGESNury Turkel, chairman of the Uighur Human Rights Project in Washington, said the Uighurs were being “detained and tormented” and “swept into a vast system of forced labor” in Xinjiang.

In testimony to US congress, he said it was becoming “increasingly hard to ignore the fact” that the goods manufactured in the region have “a high likelihood” of being produced with forced labour.

Which brands use Xinjiang cotton?

Amy Lehr, director of CSIS Human Rights Initiative, said in many cases Western companies aren’t buying directly from factories in Xinjiang.

“Rather, the products may go through several stages of transformation after leaving Xinjiang before they are sent to large Western brands,” she said.

Some, like Muji, are very open about sourcing material from Xinjiang.

The Japanese retail chain launched a new Xinjiang Cotton collection earlier this year.

One of its advertisements boasts “soft and breathable” men’s shirts made from organic cotton “delicately and wholly handpicked in Xinjiang”.

Another Japanese fashion brand Uniqlo had also touted the Xinjiang region in an advertisement advertisment for men’s shirts.

In the fine print of the shirt description, the advert said the shirts were made from Xinjiang cotton, “famous for its superb quality”.

That reference was later removed from the advertisement “given the complexity of this issue”, according to a spokesperson for Uniqlo.

“Uniqlo does not have any production partners located in the Xinjiang region. Moreover, Uniqlo production partners must commit to our strict company code of conduct.

“To the best of our knowledge, this means our cotton comes only from ethical sources,” the spokesperson told the BBC.

Image copyright GETTY IMAGES

Image copyright GETTY IMAGESAccording to the Wall Street Journal report which focused on workers at a mill operated by Huafu Fashion in Aksu, Xinjiang, yarn made in the region was present in the supply chains of several international retailers including H&M, Esprit and Adidas.

Many of the companies looked into the allegations, including those without clear links to the Huafu mill.

In a statement to the BBC, Adidas said: “While we do not have a contractual relationship with Huafu Fashion Co., or any direct leverage with this business entity or its subsidiary, we are currently investigating these claims.”

“We advised our material suppliers to place no orders with Huafu until we have completed those investigations,” the Adidas spokesperson said.

Esprit, which also does not source cotton directly from Xinjiang, said it had made several inquiries earlier this year.

“We concluded that a very small amount of cotton from a Huafu factory in Xinjiang was used in a limited number of Esprit garments,” the firm said in a statement.

The company has instructed all suppliers to not source Huafu yarn from Aksu, the statement said.

H&M said it does not have “a direct or indirect business relationship” with any garment manufacturer in the Xinjiang region.

“We have an indirect business relationship with Huafu’s spinning unit in Shanyu, which is not located in the Xinjiang region, and according to our data, the vast majority of the yarn used for our garment manufacturing comes from this spinning unit,” a spokesperson for H&M said.

“Since we have an indirect business relationship with the yarn supplier Huafu, we also asked for access to their spinning facilities in Aksu. Our investigations showed no evidence of forced labor.”

Source: The BBC