Image copyright GETTY IMAGES

Image copyright GETTY IMAGESChina’s extraordinary rise was a defining story of the 20th Century, but as it prepares to mark its 70th anniversary, the BBC’s John Sudworth in Beijing asks who has really won under the Communist Party’s rule.

Sitting at his desk in the Chinese city of Tianjin, Zhao Jingjia’s knife is tracing the contours of a face.

Cut by delicate cut, the form emerges – the unmistakable image of Mao Zedong, founder of modern China.

The retired oil engineer discovered his skill with a blade only in later life and now spends his days using the ancient art of paper cutting to glorify leaders and events from China’s communist history.

“I’m the same age as the People’s Republic of China (PRC),” he says. “I have deep feelings for my motherland, my people and my party.”

Born a few days before 1 October 1949 – the day the PRC was declared by Mao – Mr Zhao’s life has followed the dramatic contours of China’s development, through poverty, repression and the rise to prosperity.

Now, in his modest but comfortable apartment, his art is helping him make sense of one of the most tumultuous periods of human history.

“Wasn’t Mao a monster,” I ask, “responsible for the deaths of tens of millions of his countrymen?”

“I lived through it,” he replies. “I can tell you that Chairman Mao did make some mistakes but they weren’t his alone.”

“I respect him from my heart. He achieved our nation’s liberation. Ordinary people cannot do such things.”

On Tuesday, China will present a similar, glorious rendering of its record to the world.

The country is staging one of its biggest ever military parades, a celebration of 70 years of Communist Party rule as pure, political triumph.

Beijing will tremble to the thunder of tanks, missile launchers and 15,000 marching soldiers, a projection of national power, wealth and status watched over by the current Communist Party leader, President Xi Jinping, in Tiananmen Square.

An incomplete narrative of progress

Like Mr Zhao’s paper-cut portraits, we’re not meant to focus on the many individual scars made in the course of China’s modern history.

It is the end result that matters.

Image copyright XINHUA/AFP

Image copyright XINHUA/AFPAnd, on face value, the transformation has been extraordinary.

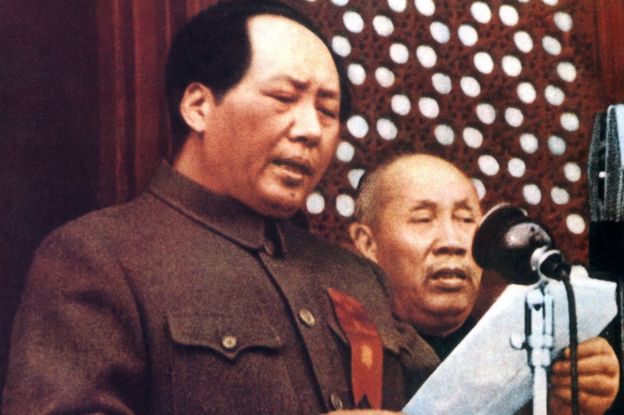

On 1 October 1949, Chairman Mao stood in Tiananmen Square urging a war-ravaged, semi-feudal state into a new era with a founding speech and a somewhat plodding parade that could muster only 17 planes for the flyby.

This week’s parade, in contrast, will reportedly feature the world’s longest range intercontinental nuclear missile and a supersonic spy-drone – the trophies of a prosperous, rising authoritarian superpower with a 400 million strong middle class.

It is a narrative of political and economic success that – while in large part true – is incomplete.

New visitors to China are often, rightly, awe-struck by the skyscraper-festooned, hi-tech megacities connected by brand new highways and the world’s largest high-speed rail network.

Image copyright GETTY IMAGES

Image copyright GETTY IMAGESThey see a rampant consumer society with the inhabitants enjoying the freedom and free time to shop for designer goods, to dine out and to surf the internet.

“How bad can it really be?” the onlookers ask, reflecting on the negative headlines they’ve read about China back home.

The answer, as in all societies, is that it depends very much on who you are.

Many of those in China’s major cities, for example, who have benefited from this explosion of material wealth and opportunity, are genuinely grateful and loyal.

In exchange for stability and growth, they may well accept – or at least tolerate – the lack of political freedom and the censorship that feature so often in the foreign media.

For them the parade could be viewed as a fitting tribute to a national success story that mirrors their own.

But in the carving out of a new China, the knife has cut long and deep.

The dead, the jailed and the marginalised

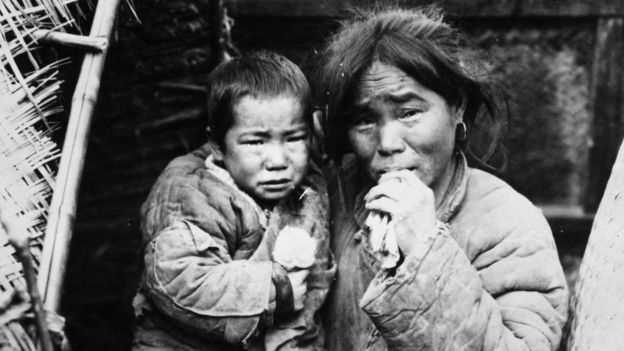

Mao’s man-made famine – a result of radical changes to agricultural systems – claimed tens of millions of lives and his Cultural Revolution killed hundreds of thousands more in a decade-long frenzy of violence and persecution, truths that are notably absent from Chinese textbooks.

Image copyright GETTY/TOPICAL

Image copyright GETTY/TOPICALAfter his death, the demographically calamitous One Child Policy brutalised millions over a 40-year period.

Still today, with its new Two Child Policy, the Party insists on violating that most intimate of rights – an individual’s choice over her fertility.

The list is long, with each category adding many thousands, at least, to the toll of those damaged or destroyed by one-party rule.

Image copyright GETTY IMAGES

Image copyright GETTY IMAGESThere are the victims of religious repression, of local government land-grabs and of corruption.

There are the tens of millions of migrant workers, the backbone of China’s industrial success, who have long been shut out of the benefits of citizenship.

A strict residential permit system continues to deny them and their families the right to education or healthcare where they work.

And in recent years, there are the estimated one and a half million Muslims in China’s western region of Xinjiang – Uighurs, Kazakhs and others – who have been placed in mass incarceration camps on the basis of their faith and ethnicity.

China continues to insist they are vocational schools, and that it is pioneering a new way of preventing domestic terrorism.

- How did one man come to embody China’s destiny?

- China’s hidden camps: What’s happened to the vanished Uighurs?

- Searching for truth in China’s ‘re-education’ camps

- China’s Muslim ‘crackdown’ explained

The stories of the dead, the jailed and the marginalised are always much more hidden than the stories of the assimilated and the successful.

Viewed from their perspective, the censorship of large parts of China’s recent history is not simply part of a grand bargain to be exchanged for stability and prosperity.

- 1949 Mao declares the founding of the People’s Republic of China

- 1966-76 Cultural Revolution brings social and political upheaval

- 1977 Deng Xiaoping initiates major reforms of China’s economy

- 1989 Army crushes Tiananmen Square pro-democracy protests

- 2010 China becomes the world’s second-largest economy

- 2018 Xi Jinping is cleared to be president for life

It is the job of foreign journalists, of course, to try.

‘Falsified, faked and glorified’

But while censorship can shut people up, it cannot stop them remembering.

Prof Guo Yuhua, a sociologist at Beijing’s Tsinghua University, is one of the few scholars left trying to record, via oral histories, some of the huge changes that have affected Chinese society over the past seven decades.

Her books are banned, her communications monitored and her social media accounts are regularly deleted.

“For several generations people have received a history that has been falsified, faked, glorified and whitewashed,” she tells me, despite having been warned not to talk to the foreign media ahead of the parade.

“I think it requires the entire nation to re-study and to reflect on history. Only if we do that can we ensure that these tragedies won’t be repeated.”

Image copyright GETTY IMAGES

Image copyright GETTY IMAGESA parade, she believes, that puts the Communist Party at the front and centre of the story, misses the real lesson, that China’s progress only began after Mao, when the party loosened its grip a bit.

“People are born to strive for a better, happier and more respectful life, aren’t they?” she asks me.

“If they are provided with a tiny little space, they’ll try to make a fortune and solve their survival problems. This shouldn’t be attributed to the leadership.”

‘Our happiness comes from hard work’

As if to prove the point about how the unsettled, censored pasts of authoritarian states continue to impact the present, the parade is for invited guests only.

Image copyright GETTY IMAGES

Image copyright GETTY IMAGESAnother anniversary, of which Tiananmen Square is the centrepiece, is also being measured in multiples of 10 – it is 30 years since the bloody suppression of the pro-democracy protests that shook the foundations of Communist Party rule.

The troops will be marching – as they always do on these occasions – down the same avenue on which the students were gunned down.

The risk of even a lone protester using the parade to mark a piece of history that has largely been wiped from the record is just too great.

With central Beijing sealed off, ordinary people in whose honour it is supposedly being held, can only watch it on TV.

Back in his Tianjin apartment, Zhao Jingjia shows me the intricate detail of a series of scenes, each cut from a single piece of paper, depicting the “Long March”, a time of hardship and setback for the Communist Party long before it eventually swept to power.

“Our happiness nowadays comes from hard work,” he tells me.

It is a view that echoes that of the Chinese government which, like him, has at least acknowledged that Mao made mistakes while insisting they shouldn’t be dwelt on.

“As for the 70 years of China, it’s extraordinary,” he says. “It can be seen by all. Yesterday we sent two navigation satellites into space – all citizens can enjoy the convenience that these things bring us.”