19/04/2020

- Faced with a backlash from the West over its handling of the early stages of the pandemic, Beijing has been quietly gaining ground in Asia

- Teams of experts and donations of medical supplies have been largely welcomed by China’s neighbours

Despite facing some criticism from the West, China’s Asian neighbours have welcomed its medical expertise and vital supplies. Photo: Xinhua

While China’s campaign to mend its international image in the wake of its handling of the

coronavirus health crisis has been met with scepticism and even a backlash from the US and its Western allies, Beijing has been quietly gaining ground in Asia.

Teams of experts have been sent to Cambodia, the Philippines, Myanmar, Pakistan and soon to Malaysia, to share their knowledge from the pandemic’s ground zero in central China.

Beijing has also donated or facilitated shipments of medical masks and ventilators to countries in need. And despite some of the equipment failing to meet Western quality standards, or being downright defective, the supplies have been largely welcomed in Asian countries.

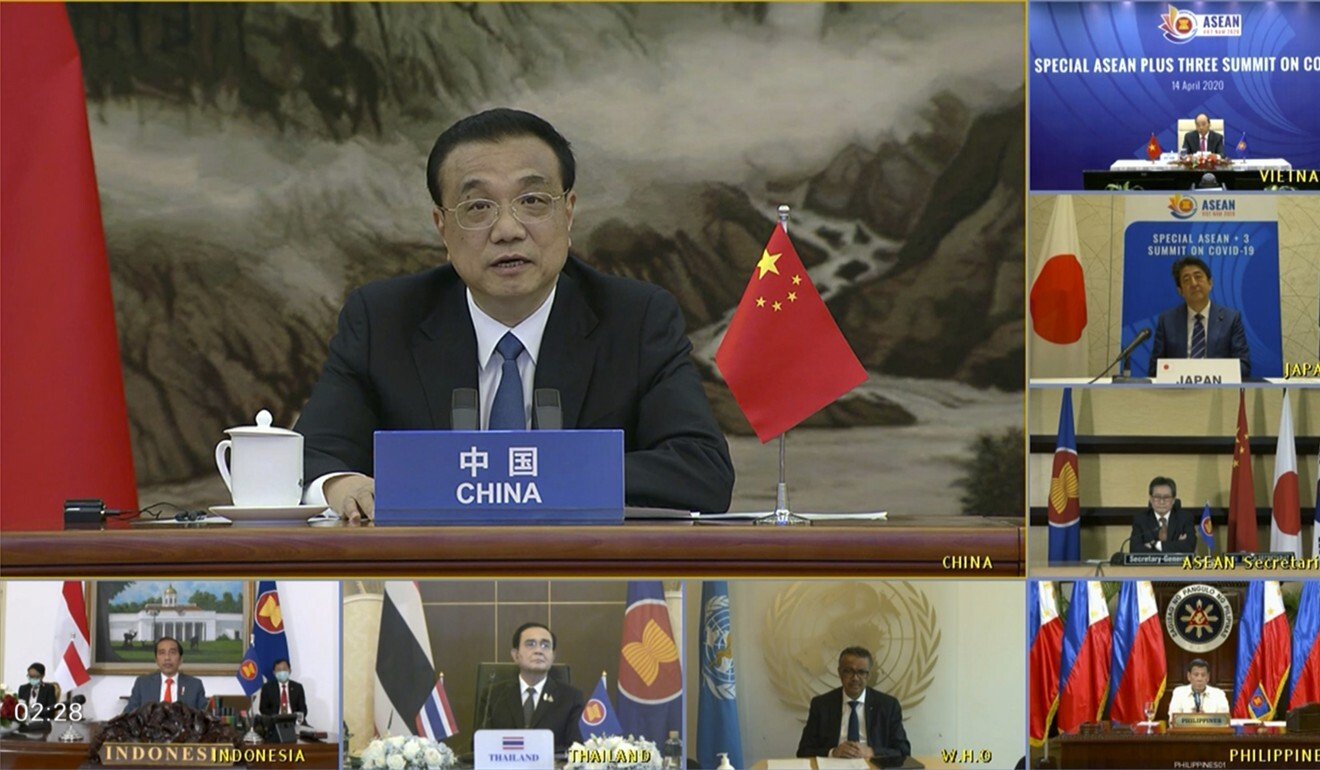

China has also held a series of online “special meetings” with its Asian neighbours, most recently on Tuesday when Premier Li Keqiang discussed his country’s experiences in combating the disease and rebooting a stalled economy with the leaders of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean), Japan and South Korea.

Chinese Prime Minister Li Keqiang speaks to Asean Plus Three leaders during a virtual summit on Tuesday. Photo: AP

Many Western politicians have publicly questioned Beijing’s role and its subsequent handling of the crisis but Asian leaders – including Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte and Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe – have been reluctant to blame the Chinese government, while also facing criticism at home for not closing their borders with China soon enough to prevent the spread of the virus.

An official from one Asian country said attention had shifted from the early stages of the outbreak – when disgruntled voices among the public were at their loudest – as people watched the virus continue its deadly spread through their homes and across the world.

“Now everybody just wants to get past the quarantine,” he said. “China has been very helpful to us. It’s also closer to us so it’s easier to get shipments from them. The [medical] supplies keep coming, which is what we need right now.”

The official said also that while the teams of experts sent by Beijing were mainly there to observe and offer advice, the gesture was still appreciated.

Another Asian official said the tardy response by Western governments in handling the outbreak had given China an advantage, despite its initial lack of transparency over the outbreak.

“The West is not doing a better job on this,” he said, adding that his government had taken cues from Beijing on the use of propaganda in shaping public opinion and boosting patriotic sentiment in a time of crisis.

“Because it happened in China first, it has given us time to observe what works in China and adopt [these measures] for our country,” the official said.

Experts in the region said that Beijing’s intensifying campaign of “mask diplomacy” to reverse the damage to its reputation had met with less resistance in Asia.

Why China’s ‘mask diplomacy’ is raising concern in the West

“Over the past two months or so, China, after getting the Covid-19 outbreak under control, has been using a very concerted effort to reshape the narrative, to pre-empt the narrative that China is liable for this global pandemic, that China has to compensate other countries,” said Richard Heydarian, a Manila-based academic and former policy adviser to the Philippine government.

“It doesn’t help that the US is in lockdown with its domestic crisis and that we have someone like President Trump who is more interested in playing the blame game rather than acting like a global leader,” he said.

Shahriman Lockman, a senior analyst with the foreign policy and security studies programme at Malaysia’s Institute of Strategic and International Studies, said that as the US had withdrawn into its own affairs as it struggled to contain the pandemic, China had found Southeast Asia a fertile ground for cultivating an image of itself as a provider.

China’s first-quarter GDP shrinks for the first time since 1976 as coronavirus cripples economy

Beijing’s highly publicised delegations tasking medical equipment and supplies had burnished that reputation, he said, adding that the Chinese government had also “quite successfully shaped general Southeast Asian perceptions of its handling of the pandemic, despite growing evidence that it could have acted more swiftly at the early stages of the outbreak in Wuhan”.

“Its capacity and will to build hospitals from scratch and put hundreds of millions of people on lockdown are being compared to the more indecisive and chaotic responses seen in the West, especially in Britain and the United States,” he said.

Coronavirus droplets may travel further than personal distancing guidelines

Lockman said Southeast Asian countries had also been careful to avoid getting caught in the middle of the deteriorating relationship between Beijing and Washington as the two powers pointed fingers at each other over the origins of the new coronavirus.

“The squabble between China and the United States about the pandemic is precisely what Asean governments would go to great lengths to avoid because it is seen as an expression of Sino-US rivalry,” he said.

“Furthermore, the immense Chinese market is seen as providing an irreplaceable route towards Southeast Asia’s post-pandemic economic recovery.”

Aaron Connelly, a research fellow in Southeast Asian political change and foreign policy with the International Institute for Strategic Studies in Singapore, said Asian countries’ dependence on China had made them slow to blame China for the pandemic.

“Anecdotally, it seems to me that most Southeast Asian political and business elites have given Beijing a pass on the initial cover-up of Covid-19, and high marks for the domestic lockdown that followed,” he said.

“This may be motivated reasoning, because these elites are so dependent on Chinese trade and investment, and see little benefit in criticising China.”

China and Vietnam ‘likely to clash again’ as they build maritime militias

The cooperation with its neighbours as they grapple with the coronavirus had not slowed China’s military and research activities in the disputed areas of the

South China Sea – a point of contention that would continue to cloud relations in the region, experts said.

Earlier this month an encounter in the South China Sea with a Chinese coastguard vessel led to the sinking of a fishing boat from Vietnam, which this year assumed chairmanship of Asean.

And in a move that could spark fresh regional concerns, shipping data on Thursday showed a controversial Chinese government survey ship, the Haiyang Dizhi 8, had moved closer to Malaysia’s exclusive economic zone.

The survey ship was embroiled in a months-long stand-off last year with Vietnamese vessels within Hanoi’s exclusive economic zone and was spotted again on Tuesday 158km (98 miles) off the Vietnamese coast.

Source: SCMP

Posted in 10, 13, 15, 16, 17, 18, 1976, 27, 44, 50%, 54, according, across the world, again, against, April, areas, arriving, ASEAN, Asian, Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), ASYMPTOMATIC CASES, at, authorities, avoid, ‘mask diplomacy’, battling, Beijing, Beijing’s, biggest, blame, blame game, borders, Britain, build, burnished, cabinet, cases, cautioning, central, central district, chairmanship, China, China's, China’s National Health Commission, Chinese capital, chinese government, Chinese market, City, clinical, closer, closing, coast, coastguard vesse, coastguard vessel, combating, compensate, confirmed, confirmed cases, considered, contain, contention, control, controversial, coronavirus, coronavirus cases, cough, countries, country’s, COVID-19, COVID-19 outbreak, cripples, crisis, criticism, cross infections, Data, day, deadly spread, death toll, deaths, declines, delegations, despite, destabilising, Disease, disputed areas, districts, domestic, down, earlier, eastern, economic recovery, economically, economy, elsewhere, embroiled, epicentre, epidemic, everybody, exclusive economic zones, experiences, eyes, facing, fall, family gatherings, fever, first time, fishing boat, flare-up, foreign policy and security studies programme, Friday, from, GDP, global leader, global pandemic, Government, Guangzhou, Haiyang Dizhi 8, handling, Hanoi’s, Harbin, health commission, Heilongjiang, high-risk, Home, hospitals, However, hubei province, hundreds, imported, imported infections, including, infected, Institute of Strategic and International Studies, interested, International Institute for Strategic Studies, investigations, irreplaceable, Japan, Japanese Prime Minister, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, Jiaozhou, km, last, leaders, local, locally, lockdown, low-risk, lowest, mainland, Mainland China, Major, Malaysia’s, March, medical equipment and supplies, medium-risk, miles, military and research activities, millions, months-long, moved, narrative, new, nine, Northeastern, Notably, now, number, off, Official, officials, on guard, outbreak, patients, People, perceptions, Philippine, playing, political, politicians, Post, post-pandemic, pre-empt, Premier Li Keqiang, present, President Trump, prevent, previous, province, provincial capital, provincial government, publicly, published, punished, quarantine, questioned, quickly, quoted, reached, rebooting, rebound, recent, reluctant, remaining, reported, reporting, reputation, research fellow, reshape, resurgence, role, route, Russia, Saturday, saying, scratch, seen, senior analyst, shandong province, shipping data, showed, shrinks, since, Singapore, sinking, Sino-US rivalry, slow, social media, socially, soon enough, South China Sea, South Korea, Southeast Asia, Southeast Asian political change and foreign policy, southern city, spotted, spread, squabble, stalled, stand-off, State Council, statement, stood, stop, subsequent, Suifenhe, Sunday, surge, survey ship, symptoms, tally, task, test positive, Three, Thursday, Total, towards, transmitted, Transparency, travellers, Tuesday, two, Uncategorized, United States, vice governor, vice mayor, Vietnam, Vietnamese, Vietnamese vessels, virtual summit, Virus, Washington, website, weeks, were, Western, within, Wuhan, year |

Leave a Comment »

31/07/2019

- China suggests good progress made in Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership talks after marathon 10-day negotiations in Zhengzhou

- Indian Commerce Minister Piyush Goyal has opted to skip the upcoming high-level meetings, adding fuel to rumours that the country could be removed

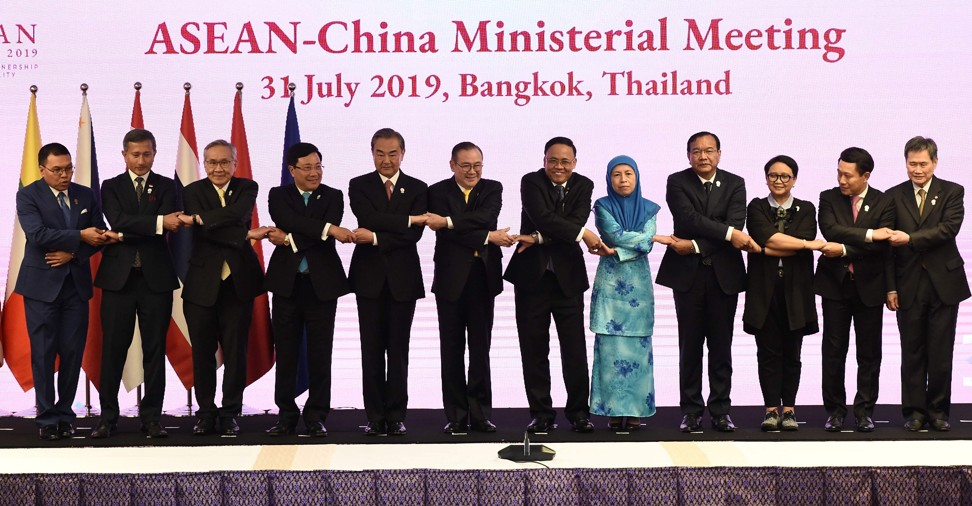

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean) has overtaken the US to become China’s second-largest trading partner in the first half of 2019. Photo: AP

China has claimed “positive progress” towards finalising the world’s largest free-trade agreement by the end of 2019 after hosting 10 days of talks, but insiders have suggested there was “never a chance” of concluding the deal in Zhengzhou.

The 27th round of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) negotiations closed on Wednesday in the central Chinese city.

working level conference brought over 700 negotiators from all 16 member countries to Henan province, with China keen to push through a deal which has proven extremely difficult to close.

If finalised, the agreement, which involves the 10 Asean nations, as well as China, Japan, South Korea, Australia, New Zealand, and India, would cover around one-third of the global gross domestic product, about 40 per cent of world trade and almost half the world’s population.

“This round of talks has made positive progress in various fields,” said assistant minister of commerce Li Chenggang, adding that all parties had reaffirmed the goal of concluding the deal this year. “China will work together with the RCEP countries to proactively push forward the negotiation, strive to resolve the remaining issues as soon as possible, and to end the negotiations as soon as possible.”

China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi (fifth left) poses with foreign ministers from the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean) countries during the ASEAN-China Ministerial Meeting in Bangkok. Photo: AFP

China is keen to complete a deal which would offer it a buffer against the United States in Asia, and which would allow it to champion its free trade position, while the US pursues protectionist trade policy.

The RCEP talks took place as Chinese and American trade negotiators resumed face-to-face discussions in Shanghai, which also ended on Wednesday, although there was little sign of similar progress.

As the rivalry between Beijing and Washington has intensified and bilateral trade waned, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean) overtook the US to become China’s second-largest trading partner in the first half of 2019. From January to June, the trade volume between China and the 10-member bloc reached US$291.85 billion, up by 4.2 per cent from a year ago, according to government data.

The Asean bloc is made up of Indonesia, Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore, Philippines, Vietnam, Myanmar, Cambodia, Brunei and Laos.

China will work together with the RCEP countries to proactively push forward the negotiation, strive to resolve the remaining issues as soon as possible, and to end the negotiations as soon as possible. Li Chenggang

RCEP talks will now move to a higher level ministerial meeting in Beijing on Friday and Saturday, but trade experts have warned that if material progress is not made, it is likely that the RCEP talks will continue into 2020, prolonging a saga which has already dragged on longer than many expected. It is the first time China has hosted the ministerial level talks.

But complicating matters is the fact that India’s Commerce Minister, Piyush Goyal, will not attend the ministerial level talks, with an Indian government official saying that he has to participate in an extended parliamentary session.

India is widely viewed as the biggest roadblock to concluding RCEP, the first negotiations for which were held in May 2013 in Brunei. Delhi has allegedly opposed opening its domestic markets to tariff-free goods and services, particularly from China, and has also had issues with the rules of origin chapter of RCEP.

China is understood to be “egging on” other members to move forward without India, but this could be politically explosive, particularly for smaller Asean nations, a source familiar with talks said.

Deborah Elms, executive director of the Asian Trade Centre, a Singapore-based lobby group, said that after the last round of negotiations in Melbourne between June 22 to July 3 – which she attended – there was “frustration” at India’s reluctance to move forward.

She suggested that in India’s absence, ministers in China could decide to move forward through a “pathfinder” agreement, which would remove India, but also potentially Australia and New Zealand.

India’s Commerce Minister, Piyush Goyal, will not attend the ministerial level talks this week in Beijing. Photo: Bloomberg

This “Asean-plus three” deal would be designed to encourage India to come on board, Elms said, but would surely not go down well in Australia and New Zealand, which have been two of the agreement’s biggest supporters.

New Zealand has had objections to the investor protections sections of RCEP, and both countries have historically been pushing for a more comprehensive deal than many members are comfortable with, since both already have free trade agreements with many of the other member nations.

However, their exclusion would be due to “an unfortunate geographical problem, which is if you’re going to kick out India, there has always been an Asean-plus three concept to start with”. Therefore it is easier to exclude Australia and New Zealand, rather than India alone, which would politically difficult.

A source close to the negotiating teams described the prospect of being cut out of the deal at this late stage as a “frustrating rumour”, adding that “as far as I know [it] has no real basis other than a scare tactic against India”.

There was “never a chance of concluding [the deal during] this round, but good progress is being made is what I understand. The key issues remain India and China”, said the source, who wished to remain anonymous.

Replacing bilateral cooperation with regional collaborations is a means of resolving the disputesTong Jiadong

However, Tong Jiadong, a professor of international trade at the Nankai University of Tianjin, said Washington’s refusal to recognise India as a developing country at the World Trade Organisation could nudge the world’s second most populous nation closer to signing RCEP.

“That might push India to the RCEP, accelerating the pace of RCEP,” Tong said, adding that ongoing trade tensions between Japan and South Korea could also be soothed by RCEP’s passage.

“Replacing bilateral cooperation with regional collaborations is a means of resolving the disputes between the two countries,” Tong said.

Although the plan was first proposed by the Southeast Asian countries, China has been playing an increasingly active role, first as a response to the now defunct US-backed Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), and more recently as a means of containing the impact of the trade war.

China’s vice-commerce Minister, Wang Shouwen, told delegates last week that RCEP was “the most important free trade deal in East Asia”. He called on all participants to “take full advantage of the good momentum and accelerating progress at the moment” to conclude a deal by the end of the year.

Source: SCMP

Posted in Asean nations, ASEAN-China Ministerial Meeting, Asia, Asian Trade Centre, Australia, Bangkok, Beijing, biggest roadblock, Brunei, Cambodia, China alert, claims, Delhi, Henan province, India alert, Indian Commerce Minister, Indonesia, Japan, Laos, Malaysia, Melbourne, Myanmar, Nankai University of Tianjin, New Zealand, Philippines, Piyush Goyal, progress, Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), remains, rivalry, Shanghai, Singapore, South Korea, Thailand, towards, Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), Uncategorized, United States, Vietnam, Washington, World Trade Organisation (WTO), world’s biggest trade deal, Zhengzhou |

Leave a Comment »