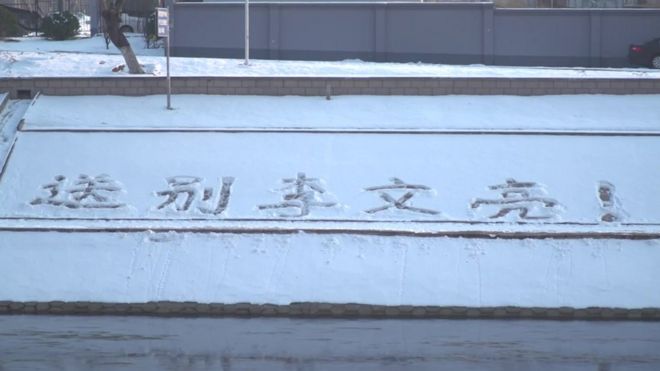

On a cold Beijing morning, on an uninspiring, urban stretch of the Tonghui river, a lone figure could be seen writing giant Chinese characters in the snow.

The message taking shape on the sloping concrete embankment was to a dead doctor.

“Goodbye Li Wenliang!” it read, with the author using their own body to make the imprint of that final exclamation mark.

Five weeks earlier, Dr Li had been punished by the police for trying to warn colleagues about the dangers of a strange new virus infecting patients in his hospital in the Chinese city of Wuhan.

Now he’d succumbed to the illness himself and pictures of that frozen tribute spread fast on the Chinese internet, capturing in physical form a deep moment of national shock and anger.

Image copyright GETTY IMAGES

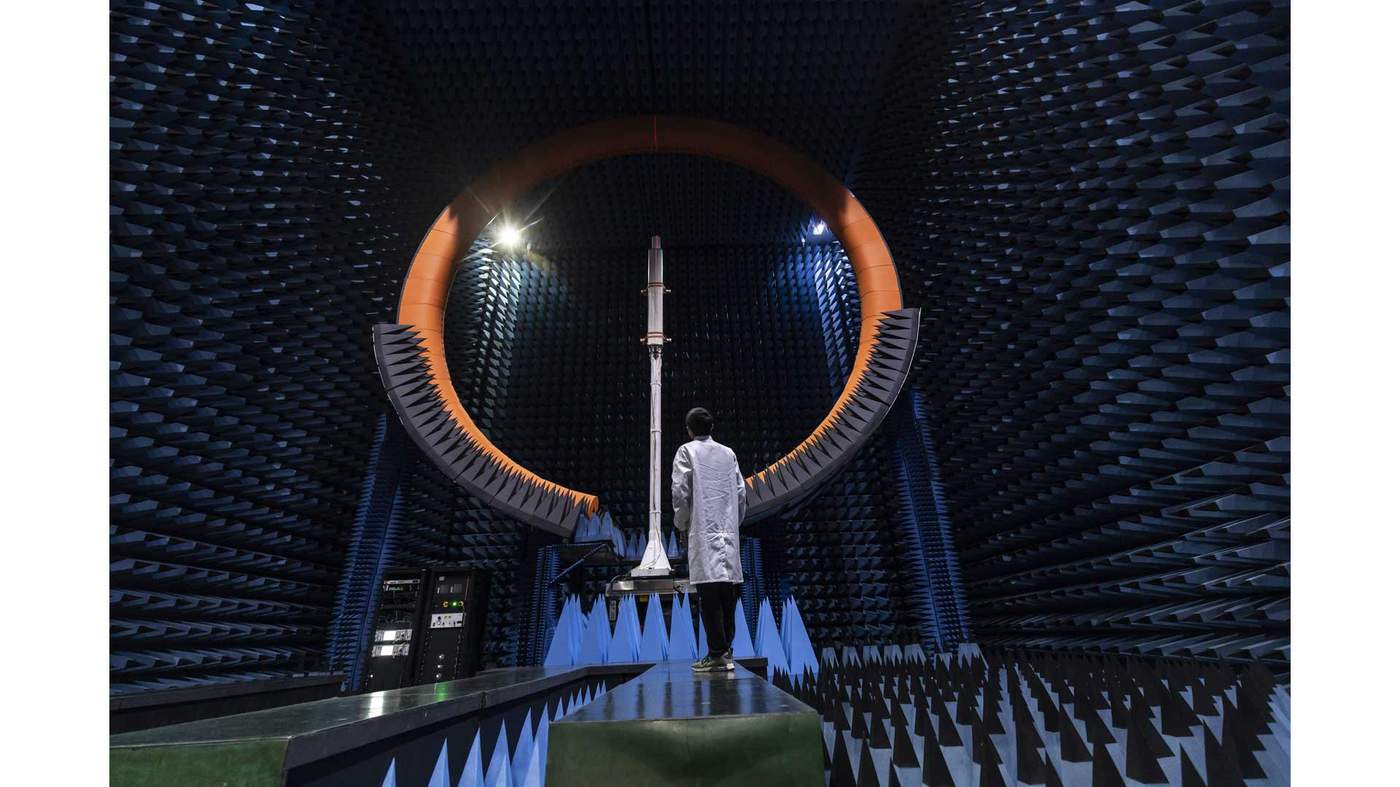

Image copyright GETTY IMAGESThere’s still a great deal we don’t know about Covid-19, to give the disease caused by the virus its official name. Before it took its final fatal leap across the species barrier to infect its first human, it is likely to have been lurking inside the biochemistry of an – as yet unidentified – animal. That animal, probably infected after the virus made an earlier zoological jump from a bat, is thought to have been kept in a Wuhan market, where wildlife was traded illegally.

Beyond that, the scientists trying to map its deadly trajectory from origin to epidemic can say little more with any certainty.

- China’s Xi visits hospital in rare appearance amid health crisis

- A visual guide to the Coronavirus outbreak

- Coronavirus super-spreaders – why are they important?

But while they continue their urgent, vital work to determine the speed at which it spreads and the risks it poses, one thing is beyond doubt. A month or so on from its discovery, Covid-19 has shaken Chinese society and politics to the core.

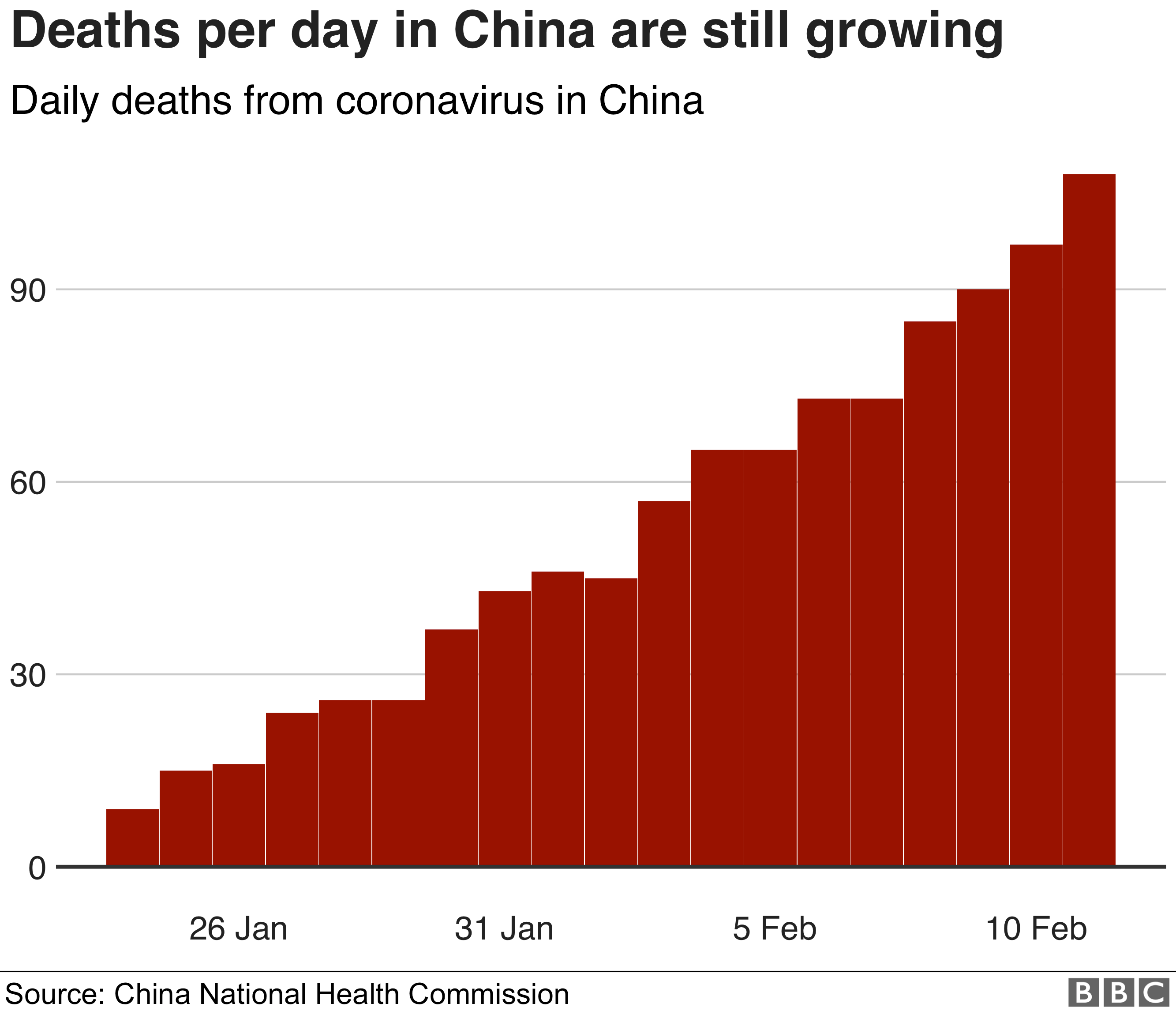

That tiny piece of genetic material, measured in ten-thousandths of a millimetre, has set in train a humanitarian and economic catastrophe counted in more than 1,000 Chinese lives and tens of billions of Chinese yuan. It has closed off whole cities, placing an estimated 70 million residents in effective quarantine, shutting down transport links and restricting their ability to leave their homes. And it has exposed the limits of a political system for which social control is the highest value, breaching the rigid layers of censorship with a tsunami of grief and rage.

The risk for the ruling elite is obvious.

It can be seen in their response, ordering into action the military, the media and every level of government from the very top to the lowliest village committee.

The consequences are now entirely dependent on questions no one knows the answers to; can they pull off the complex task of bringing a runaway epidemic under control, and if so, how long might it take?

Across the world, people seem unsure how to respond to the small number of cases being detected in their own countries. The public mood can swing between panic – driven by the pictures of medical workers in hazmat suits – to complacency, brought on by headlines that suggest the risk is no worse than flu. The evidence from China suggests that both responses are misguided. Seasonal flu may well have a low fatality rate, measured in fractions of 1%, but it’s a problem because it affects so many people around the world.

- Why much of the ‘world’s factory’ remains shut

- How worried should we be about Coronavirus?

- Your coronavirus questions answered

The tiny proportion killed out of the many, many millions who catch it each year still numbers in the hundreds of thousands – individually tragic, collectively a major healthcare burden.

Very early estimates suggested the new virus may be at least as deadly as flu – precisely why so much effort is now going into stopping it becoming another global pandemic. But one new estimate suggests it could prove even deadlier yet, killing as many as 1% of those who contract it. For any individual, that risk is still relatively small, although it’s worth noting such estimates are averages – just like flu, the risks fall more heavily on the elderly and already infirm.

Image copyright REUTERS

Image copyright REUTERSBut China’s experience of this epidemic demonstrates two things. Firstly, it offers a terrifying glimpse of the potential effect on a healthcare system when you scale up infections of this kind of virus across massive populations. Two new hospitals have had to be built in Wuhan in a matter of days, with beds for 2,600 patients, and giant stadiums and hotels are being used as quarantine centres, for almost 10,000 more.

Despite these efforts, many have still struggled to find treatment, with reports of people dying at home, unregistered in the official figures. Secondly, it highlights the importance of taking the task of containing outbreaks of new viruses extremely seriously. The best approach, most experts agree, is one based on transparency and trust, with good public information and proportionate, timely government action.

But in an authoritarian system, with strict censorship and an emphasis on political stability above all else, transparency and trust are in short supply.

China’s response may have sometimes looked like panic – with what’s been called the “biggest quarantine in history” and harsh enforcement against those who disobey.

But those measures have become necessary only because its initial response looked like the very definition of complacency.

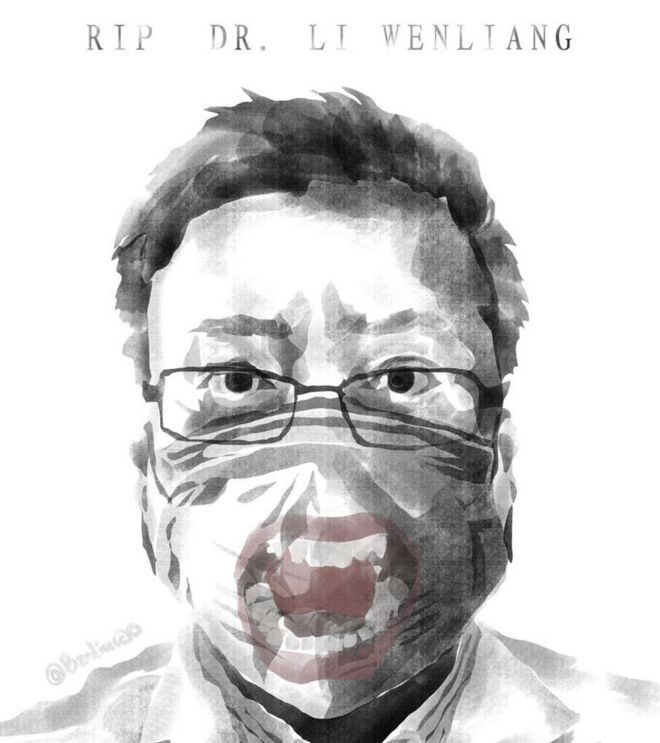

There’s ample evidence that the warning signs were missed by the authorities, and worse, ignored. By late December, medical staff in Wuhan were beginning to notice unusual symptoms of viral pneumonia, with a cluster linked to the market trading in illegal wildlife. On 30 December, Dr Li Wenliang, an ophthalmologist working in Wuhan’s Central Hospital, posted his concerns in a private medical chat group, advising colleagues to take measures to protect themselves. He’d seen seven patients who appeared to be suffering with an illness similar to Sars – another coronavirus that began in an illegal Chinese wildlife market in 2002 and went on to kill 774 people worldwide.

A few days later, he was summoned by the police.

Dr Li was made to sign a confession, denouncing the messages he’d posted as “illegal behaviour”.

The case received national media attention, with a high-profile state-run TV report announcing that in total, eight people in Wuhan were being investigated for “spreading rumours”. The authorities, though, were well aware of the outbreak of illness. The day after Dr Li posted his message, China notified the World Health Organization, and the day after that, the suspected source – the market – was closed down.

But despite the multiplying cases and the concerns among medics that human-to-human transmission was taking place, the authorities did little to protect the public. Doctors were already setting up quarantine rooms and anticipating extra admissions when Wuhan held its important annual political gathering, the city’s People’s Congress.

In their speeches, the Communist Party leaders made no mention of the virus. China’s National Health Commission continued to report that the number of infections was limited and that there was no clear evidence that the disease could spread between humans.

And on 18 January the Wuhan authorities allowed a massive community banquet to take place, involving more than 40,000 families. The aim was to set a record for the most dishes served at an event. Two days later, China finally confirmed that human-to-human transmission was indeed taking place.

Most remarkable of all perhaps, the following day, Wuhan held a Lunar New Year dance performance, attended by senior officials from across the surrounding province of Hubei. A state media report of the event, since hurriedly deleted but captured here, says the performers, some with runny noses and feeling unwell, “overcame the fear of pneumonia… winning praise from the leaders”.

By the time the national authorities had woken up to the impending disaster, and closed the city down on 23 January, it was too late – the epidemic was out of control. Before Wuhan’s transport links were cut, an estimated five million people had left the city for the Lunar New Year break, travelling across China and the world.

Some have begun calling the disaster “China’s Chernobyl”.

The parallels in failures to pass bad news up the chain of command and the incentives to put the short-term interests of political stability ahead of public safety, seem all too apparent. Li Wenliang, who’d gone back to work after being warned to keep quiet, soon discovered he’d also been infected.

He died earlier this month, leaving a five-year-old son and a pregnant wife.

Anger was already simmering over the authorities’ failure to issue timely warnings, with the crisis now being aired in full view. Wuhan’s politicians were blaming senior officials for failing to authorise the release of the information; senior officials appeared to be preparing to hang Wuhan’s politicians out to dry.

But the death of a man, silenced for simply trying to protect his colleagues, burst open the dam with a wave of online fury directed not just at individuals, but at the system itself. So great was the public outrage, China’s censors appeared unsure what to censor and what to let through. The hashtag #Iwantfreedomofspeech was viewed almost two million times before it was blocked. Aware of the tide of emotion, the Party began paying its own tributes to Dr Li.

It quickly hailed him a national hero.

Image copyright COURTESY BADIUCAO

Image copyright COURTESY BADIUCAOChina’s rulers, untroubled by the inconveniences of the ballot box, have far deeper and older fears of what might sweep them from office. The wars, famines and diseases that shook the dynasties of old have given them their inheritance; an acute historical sense of the danger of the unforeseen crisis. They will also know well what Chernobyl did for the legitimacy of the ruling Communist Party in the former USSR.

“It’s impossible to know if Li Wenliang’s death will serve as the catalyst for something bigger,” Jude Blanchette, an expert on Chinese politics at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, tells me. “But the raw emotion that surged when news of his condition broke indicates deep levels of frustration and anger exist within the country.”

Precisely because it feels the weight of history, however, the Communist Party has made holding onto power a living obsession, and it has an ever more formidable domestic security apparatus to help it to do so. Over the past few decades it has proven nothing if not resilient, enduring through political chaos, devastating earthquakes and man-made disasters.

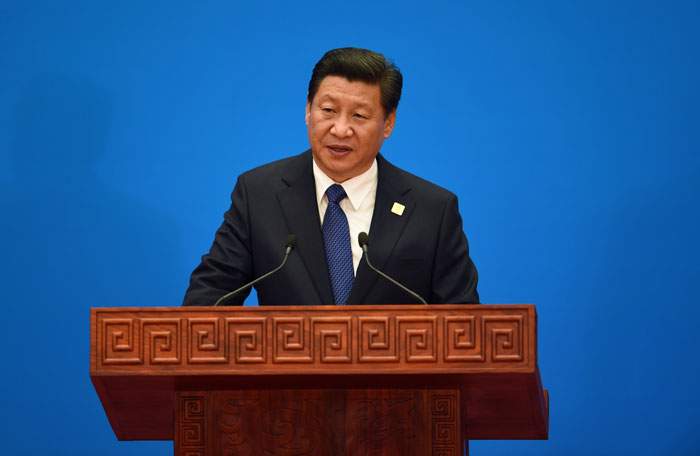

But one sign that might hint at an awareness of just how great the current risks are comes in the role being played by China’s President Xi Jinping. This week – for the first time since the crisis began – he ventured out to meet health workers involved in the fight, visiting a hospital and a virus control centre in Beijing.

In contrast, his premier, Li Keqiang, has been sent to the front lines in Wuhan and appointed head of a special working group to tackle the epidemic.

While it is common for the premier to be the face of reassurance during national disasters, some observers see another reason why Mr Xi might be wise to be seen to delegate.

Image copyright EPA

Image copyright EPA“Xi’s absence from this crisis is yet another demonstration that he doesn’t so much lead as he does command,” Mr Blanchette says. “He’s clearly worried that this crisis will blow up in his face, and so he’s pushed out underlings to be the public face of the CCP’s response.”

Already there are signs that the censorship is being ratcheted up once again, with Mr Xi ordering senior officials to “strengthen the control over online media”.

A few days ago, I spoke by phone to the lawyer and blogger, Chen Qiushi, who’d travelled to Wuhan in an attempt to provide independent reporting about the situation. Videos from Mr Chen, and a fellow activist, Fang Bin, have been widely watched, showing not the ranks of patriotic soldier-medics and the building of hospitals that fill state media coverage, but overcrowded waiting rooms and body bags.

He told me he was unsure how long he’d be able to carry on. “The censorship is very strict and people’s accounts are being closed down if they share my content,” he said.

Mr Chen has since gone missing.

Friends and family believe he’s been forced into Wuhan’s quarantine system, in an attempt to silence him.

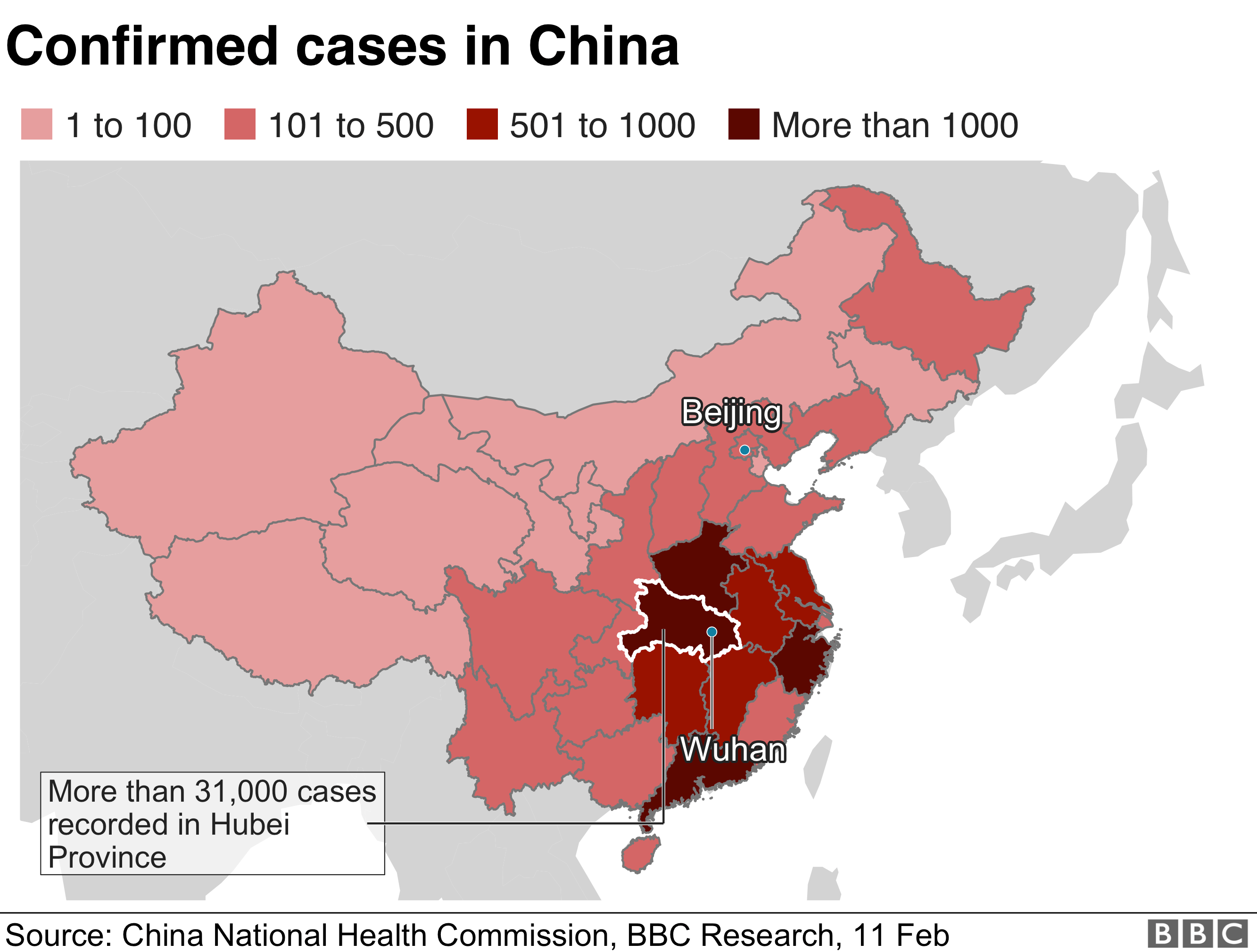

China’s leaders now find their fate linked to the daily charts of infection rates, published city by city, province by province. There are some signs that the extraordinary quarantine measures may be having an effect – outside of Hubei Province, the worst affected area, the number of new daily infections is falling.

But with the need to try to restart the economy – all but frozen now for over a week – the country has begun a slow return to work.

Strict quarantine measures will remain in force in the worst affected areas, but workers from other parts of the country are trickling back to the cities, with the task of monitoring and managing their movements being handed to local neighbourhood committees.

It will be a difficult balancing act.

Too tough an approach risks further choking off business activity, commerce and travel in a consumer environment already suffocating under the deep psychological fear of contagion. Too lax, and any one of the many potential reservoirs of infection, now scattered across the country, could explode into another, separate epidemic.

That would require further harsh action, knocking domestic confidence and prolonging the international border closures and flight restrictions put in place at such enormous economic cost.

China is insisting that it is a fight well on the way to being won with “unconquerable will” and that lessons have been learned and “shortcomings in preparedness” identified.

Questions about the systemic failings behind the disaster are dismissed as foreign “prejudice”, as the propaganda machine cranks into overdrive, channelling the narrative and muting the criticisms.

But the devastating scale and scope of China’s world-threatening catastrophe have already revealed something important. The thousands who have lost family members, the millions living under the quarantine measures and the workers and businesses bearing the financial costs have been asking those difficult questions too.

On the snowy banks of the Tonghui river, the giant tribute to Li Wenliang remains intact. When we visited, a few locals were taking photos and talking quietly to each other.

A police car crawled slowly by.

Soon, with the warming weather, the characters will be gone.

Source: The BBC