TUCUPITA, Venezuela (Reuters) – The project was meant to feed millions.

In Delta Amacuro, a remote Venezuelan state on the Caribbean Sea, a Chinese construction giant struck a bold agreement with the late President Hugo Chavez. The state-run firm would build new bridges and roads, a food laboratory, and the largest rice-processing plant in Latin America.

The 2010 pact, with China CAMC Engineering Co Ltd , would develop rice paddies twice the size of Manhattan and create jobs for the area’s 110,000 residents, according to a copy of the contract seen by Reuters.

The underdeveloped state was an ideal locale to demonstrate the Socialist Venezuelan government’s commitment to empower the poor. And the deal would show how Chavez and his eventual hand-picked successor, President Nicolas Maduro, could work with China and other allies to develop areas beyond Venezuela’s bounteous oil beds.

“Rice Power! Agricultural power!” Chavez tweeted at the time.

Nine years later, locals are hungry. Few jobs have materialized and the plant is only half-built, running at less than one percent its projected output. It hasn’t yielded a single grain of locally grown rice, according to a dozen people involved in or familiar with the development.

Yet CAMC and a select few Venezuelan partners prospered.

Venezuela paid CAMC at least $100 million (76 million pounds) for the stalled development, according to project contracts and sealed court documents from an investigation by prosecutors in Europe.

The thousands of pages of court papers, reviewed by Reuters, were filed in Andorra, the European principality where prosecutors allege Venezuelans involved in the project sought to launder kickbacks paid to them for helping secure the contract. The material on the China deal, reported here for the first time, includes confidential testimony, wiretap transcripts, bank records and other documents.

Last September, an Andorran high court judge alleged in an indictment that CAMC paid over $100 million in bribes to various Venezuelan intermediaries to secure the rice project and at least four other agricultural contracts.

The indictment charged 12 Venezuelans with crimes including money laundering and conspiracy to launder money. Among those indicted was Diego Salazar, a cousin of a former oil minister who, investigators say, enabled the contracts. Also indicted was the top representative in China at the time of state-run oil company Petroleos de Venezuela SA, or PDVSA.

Sixteen people of other nationalities were also charged and at least four other Venezuelans, one of whom was formerly ambassador in Beijing and is now the country’s top diplomat in London, are under investigation, according to the documents.

The indictment, the names of those charged, and their association with Chinese companies were reported last year by El Pais, the Spanish newspaper. A Reuters review of the case files, which are still under seal in Andorra, gleans how CAMC and other Chinese companies forged ties with many of those charged and paid to win projects the companies often didn’t complete.

The result, according to prosecutors, was a far-reaching culture of kickbacks, paid through offshore accounts, in which well-connected Venezuelan intermediaries milked and ultimately crippled projects that were meant to develop neglected corners of the country.

Among other findings reported here for the first time:

• CAMC agreed to at least five agricultural projects in Venezuela, valued at about $3 billion, that it never completed.

• The company, according to contracts and project documents reviewed by Reuters, received at least half the value of the $200 million contract for the rice project and at least 40 percent of the contract value for the other four developments – a combined total of at least $1.4 billion for work it never finished.

• CAMC paid over $100 million in fees to intermediaries; prosecutors say those payments were kickbacks that helped the company win contracts in Venezuela.

Neither CAMC nor any of its executives were charged in the indictment.

In a statement, the Beijing-based company told Reuters the details and assertions in the case files include “a large number of inaccuracies,” but didn’t elaborate. The company didn’t respond to requests to speak with CAMC executives mentioned in the documents. Reuters couldn’t reach those executives independently.

“Our company operates in Venezuela in adherence to the idea of integrity and strives to complete every construction project with the best technology and management,” the statement said.

China’s Foreign Ministry, in a statement to Reuters, said “reports” about alleged bribery by Chinese companies in Venezuela “obviously distorted and exaggerated facts, with a hidden agenda.” It didn’t specify to what agenda it was referring. Cooperation between the two countries will continue, the statement read, “based on equal, mutually beneficial, and commercial principles.”

Venezuela’s Information Ministry, responsible for government communications, and oil giant PDVSA, a partner in many of the contracts cited in the court case, didn’t respond to Reuters inquiries.

It isn’t clear when any of those charged could face trial. Enric Gimenez, a lawyer in Andorra for Salazar, the Venezuelan who prosecutors say brokered many of the contracts, told Reuters his client is innocent of the charges there.

The leftist regime founded by Chavez and now led by Maduro is facing its most serious threat yet. Opposition lawmakers, with the support of most Western democracies, say Maduro’s re-election last year was illegal and that Juan Guaido, head of the National Assembly, is the country’s rightful leader.

Last week, in a failed uprising, Guaido unsuccessfully sought to rally Venezuela’s military, the lynchpin of support for the unpopular government, against Maduro.

The political crisis was prompted by an economic meltdown of hyperinflation, mass unemployment and an exodus of desperate citizens. Venezuelans suffer regular shortages of food, power and water – basics that were meant to improve through projects like the one in Delta Amacuro.

The dire scarcities and dysfunctional projects, the opposition alleges, illustrate how corruption and crony capitalism helped impoverish the once-prosperous country and many of its 30 million people.

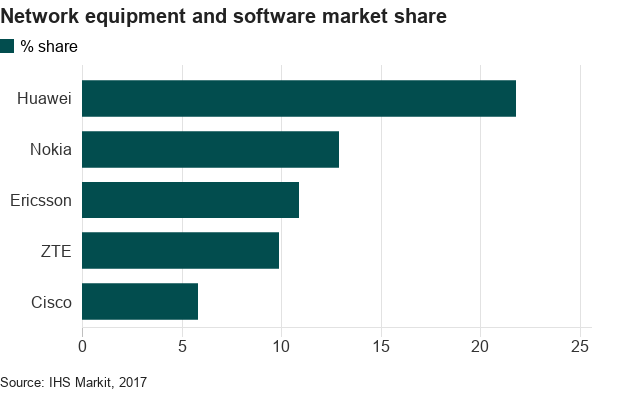

After an ambitious 2007 agreement between China and Venezuela, Chinese companies were announced as partners in billions of dollars’ worth of infrastructure and other projects. Since then, China invested over $50 billion in Venezuela, mostly in the form of oil-for-loan agreements, government figures show.

In a 2017 speech, Maduro said 790 projects with Chinese companies had been contracted in sectors ranging from oil to housing to telecommunications. Of those, he said, 495 were complete. Some developments have stalled because of graft, people familiar with the projects said; others were derailed by incompetence and a lack of supervision.

In Delta Amacuro, even government officials say a mixture of both ruined the rice project. “The government abandoned it,” says Victor Meza, state coordinator for Venezuela’s rural development agency, which worked with CAMC. “Everything was lost. Everything was stolen.”

Prosecutors in Andorra, where secretive banking laws long made it a tax haven, launched their investigation into Venezuelan laundering amid a broader effort to clean up the local financial sector.

The indictment is part of a much larger case in which the prosecutors allege Venezuelan officials between 2009 and 2014 received more than $2 billion worth of “illegal commissions” from contractors, state companies, and other sources, often for enabling transactions with the government.

The payments, the indictment alleges, passed through accounts held at Banca Privada D’Andorra, a local bank known as BPA.

Andorra’s government, after the United States accused BPA of money laundering, took over the bank in 2015. Courts there since then have charged 25 former BPA employees with money laundering in a series of cases, including the one probing the Venezuela contracts. A spokeswoman for Andorra’s government declined to comment for this article.

In addition to the agricultural projects by CAMC, the Andorrans examined two power-plant projects by the company and four other power plants built by Sinohydro Corp, another state-owned Chinese engineering firm. None of those plants ever became fully operational, leaving towns near them subject to regular blackouts.

Sinohydro wasn’t charged in the indictment. The company didn’t respond to calls, emails and faxes seeking comment.

During a recent visit by Reuters to Delta Amacuro, the CAMC rice plant remained unfinished. Only one of its 10 silos, half full, held any grain. Some machinery was running, but processing rice imported from Brazil. The nearby paddies lay fallow, the laboratory incomplete, the roads and bridges unbuilt.

“WE DON’T PRODUCE ANYTHING”

Tucupita, a town of 86,000 residents, is Delta Amacuro’s capital. It hugs the banks of the Cano Manamo, an offshoot of the Orinoco, one of South America’s biggest rivers. Once, Tucupita was a stop for vessels shipping goods from inland factories to buyers in the Caribbean and beyond.

In 1965, the government dammed the Cano Manamo. Boat traffic stopped, fresh water receded and seawater seeped inland, degrading soils. By the time Chavez became president in 1999, little farming remained.

“When I was a kid, there was rice everywhere,” recalled Rogelio Rodriguez, a local agronomist. “Now we don’t produce anything.”

In 2009, Chavez and Xi Jinping, China’s vice president at the time, expanded a joint fund the countries had created with the 2007 development agreement. “Aren’t we grateful to China?” Chavez said at a ceremony with Xi at the presidential palace in Caracas, Venezuela’s capital.

Promising to supply Beijing with oil “for the next 500 years,” Chavez pointed toward Delta Amacuro on a map. “Look, Xi,” he said, announcing an effort to rehabilitate the region.

In attendance were CAMC Chairman Luo Yan and Rafael Ramirez, a Chavez confidante who ran PDVSA and the oil ministry for a decade.

Soon, businesses jostled to get in on the development.

Diego Salazar, a cousin of Ramirez, was well-positioned.

Salazar’s father was a communist guerrilla and author who later became a legislator and Chavez ally. His family ties and connections to lawmakers gave the younger Salazar a valuable address book he wielded at a consulting firm he operated in Caracas.

The firm, Inverdt, was owned by a Panama-based holding company he had established called Highland Assets, according to testimony Salazar gave investigators in Andorra when they first began probing his BPA account. From an office a few blocks from PDVSA headquarters, he met often with Ramirez and other top officials, according to people familiar with his activities.

Ramirez left the ministry in 2014 and was Venezuela’s ambassador to the United Nations until 2017. Since then, Maduro has publicly accused him of unspecified corruption, but Ramirez wasn’t indicted in Andorra and hasn’t formally been charged with any crime in Venezuela. He now lives abroad as an opponent of the government. Ramirez didn’t respond to Reuters emails seeking comment and couldn’t be reached otherwise.

At the time of the ceremony with Xi, Chavez was making PDVSA a hub for a growing array of developments, many of them unrelated to oil. A newly created unit known as PDVSA Agricola, for instance, was tasked with boosting food supply.

The diversification made PDVSA the conduit through which contracts, and a growing sum of money administered by Venezuela’s national development bank, were awarded.

By 2010, the filings say, the bank had received $32 billion from the China Development Bank and another $6 billion from an infrastructure fund created by Chavez.

China Development Bank didn’t respond to Reuters requests for comment.

Salazar began reaching out to Chinese executives, offering his services, as a well-connected consultant, to help broker business in Venezuela. He travelled to China monthly and began paying Venezuelan officials there to forge ties with companies including CAMC.

“My work was to convince them, through meetings, trips, and promotion, to sign contracts,” Salazar told Andorran investigators.

People familiar with the case said Salazar and his alleged associates, before the indictment, agreed to testify in Andorra because they hoped to clear their names.

In his testimony, Salazar told the Andorran investigators he chose BPA as an offshore bank because he knew other wealthy Venezuelans had done so. Nestled in a quiet valley of the Pyrenees, BPA had a reputation as a discrete money manager for clients from high-risk countries.

After Andorra submitted information requests for its case to Caracas, a Venezuelan court in 2017 ordered Salazar arrested on suspicion of corruption, money laundering and conspiracy.

Citing the Andorran probe, the Venezuelan arrest order said Salazar sought to “give legal appearance to funds originating from numerous contracts with Venezuelan state institutions.” A trial date hasn’t been set and Salazar remains jailed in Caracas. A lawyer for Salazar in Venezuela denied the charges before the court.

Gimenez, Salazar’s lawyer in Andorra, in an email to Reuters said Chinese authorities decided which companies would receive funds and that neither Salazar nor his alleged intermediaries could sway that. Inverdt, Salazar’s consulting firm, offered “professional” and “technical” services to many Chinese companies, Gimenez wrote in the email, and that “only a handful of those companies were chosen to carry out works.”

One of Salazar’s intermediaries, the indictment alleged, was Francisco Jimenez, a career engineer who was PDVSA’s envoy in Beijing and who the Andorrans indicted along with Salazar. Salazar first contacted him during a trip to China in 2010, according to testimony Jimenez gave in Andorra.

That March, Jimenez signed a “strategic alliance” with Salazar to promote Inverdt in China. Under the terms of their contract, reviewed by Reuters, Salazar agreed to pay Jimenez $7.38 million in a BPA account that Inverdt helped open. Bank records in the case files show Jimenez later received another $7 million.

Jimenez, who now lives in Panama, didn’t respond to phone calls or text messages from Reuters. Salvador Capdevila, his lawyer in Andorra, declined to comment.

Another official who prosecutors say helped Salazar was Rocio Maneiro, Venezuela’s ambassador to China and now the country’s ambassador to Britain.

Maneiro wasn’t charged in the Andorran indictment; numerous court documents, including a filing by prosecutors in relation to her testimony, refer to her as “under investigation” for payments they say she received from Salazar and for her alleged role helping him make contacts with Chinese companies.

In 2010, bank records contained in the court documents show, Salazar made a transfer of $30,000 to a Chinese account in her name, citing “services provided by Mrs. Maneiro.”

Later, Salazar made deposits totalling $13 million into a BPA account owned by a Panama-based company that Maneiro, in a disclosure document linked to the account, said belonged to her. An internal report from BPA’s anti-money laundering committee, reviewed by Reuters, also listed Maneiro as its owner.

Maneiro, through a lawyer and in a text message to Reuters, denied helping Salazar and receiving payments from him. “Those are assertions with no basis,” she wrote in the message. She told an Andorran judge that the signature on the form about the Panamanian company is forged.

The court has ordered an analysis of the signature.

“A BRIEFCASE FULL OF CONTRACTS”

By early 2010, Salazar’s outreach bore fruit.

Sinohydro, the engineering firm, that March signed a $316 million contract with PDVSA to build a power plant near the city of Maracay.

In the contract, Sinohydro agreed to pay Salazar a 10 percent fee for helping it “gain a favourable and positive position to pursue the contract.” Bank records in the case files show the company paid $49 million into Salazar’s BPA account and another $72 million after Sinohydro secured additional power plant contracts from PDVSA.

Sinohydro eventually built four plants, but none met full contract specifications, engineers say. The plant near Maracay, for example, was meant to generate as much as 382 megawatts, the contract shows. Instead, the plant is producing no more than 140 megawatts, according to Jose Aguilar, a former director at Venezuela’s state power company.

Soon, Salazar’s company was earning over $100 million a year, according to testimony by him and several aides. “He had a briefcase full of contracts,” Luis Mariano Rodriguez, a Salazar deputy also charged in the indictment, told Andorran investigators.

“We made deals with every company possible,” he added. “Some of these companies never actually carried out the projects.”

Reuters was unable to reach Rodriguez, who like Salazar has been charged with money laundering and conspiracy to launder. Gimenez, Salazar’s attorney in Andorra, also represents Rodriguez, and in the email said that Rodriguez, too, is innocent.

As money poured in, Salazar splurged, paying tens of thousands of dollars for hotel stays and spending millions on gifts. For $1 million, he bought 83 Rolex and Cartier watches at a Caracas jeweller, according to an invoice in the filings. In a Rodriguez email to BPA justifying the purchase, he said the watches were “gifted to relatives and friends.”

In April 2010, Andorran police began investigating Salazar. French investigators had asked them about a recent transaction: From his BPA account, Salazar had transferred $99,980 to a Paris hotel employee as a “tip for providing services.” It’s not clear what those services were.

By May, talks for the rice project began.

That month, Rodriguez met with Wang Hong, a CAMC vice president, in Caracas, according to a contract the men signed. In the contract, they agreed that CAMC would pay Salazar’s company 10 percent of the value of the rice contract to help it “win.”

Within months, PDVSA Agricola awarded CAMC the contract, valuing the rice development at $200 million. CAMC signed another agreement with Salazar for help securing additional projects. That June, CAMC made the first of several deposits totalling $112 million to Salazar’s BPA account, bank records show.

Workers broke ground in Delta Amacuro.

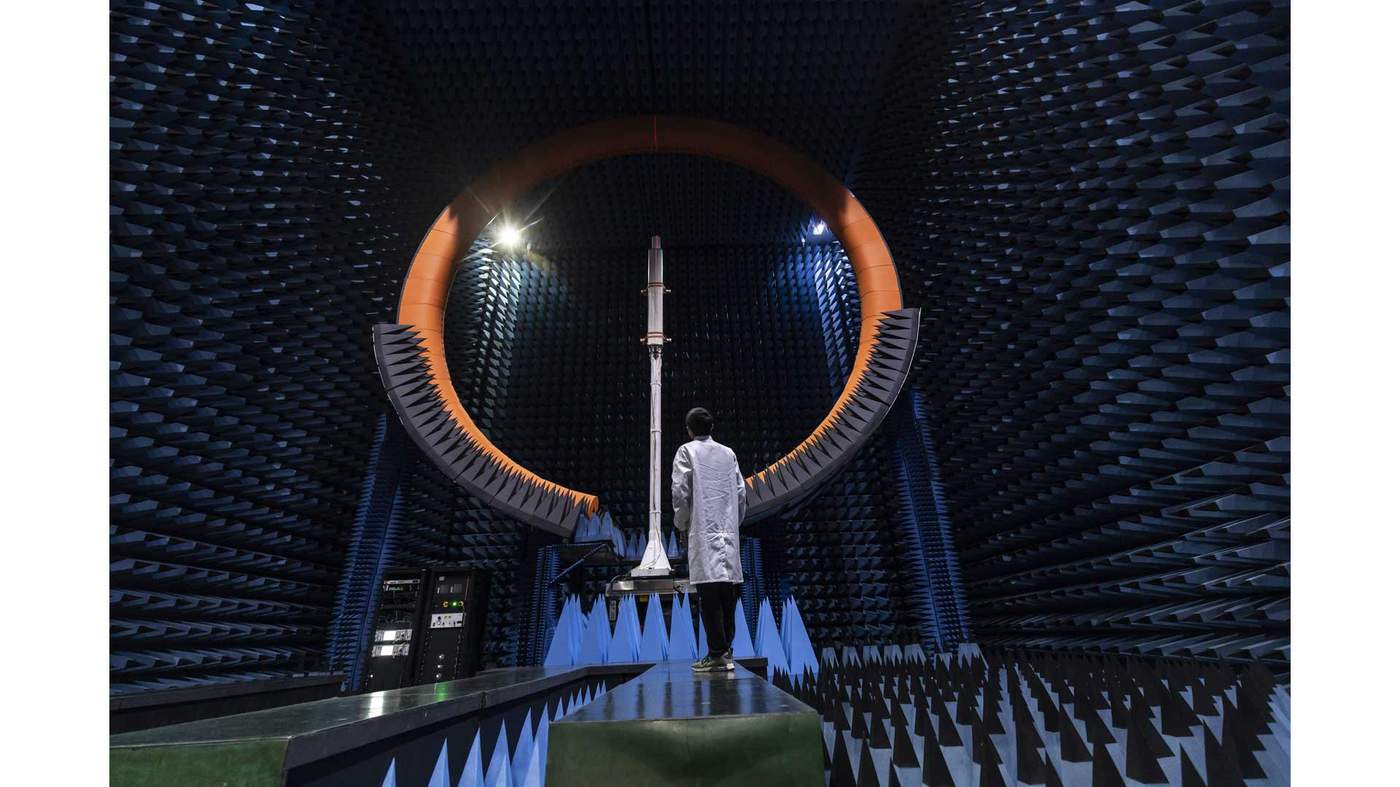

By 2012, project documents show, CAMC had received $100 million from the Venezuelan development bank for the undertaking, half that agreed upon. The company shipped excavators, steamrollers and other equipment from China.

But progress was slow.

An excavator bogged down in mud and stayed there. Chinese foremen spoke little Spanish and struggled with local crews, according to engineers who worked on the project.

That November, an Andorran court, on suspicion of money laundering, froze BPA accounts of Salazar, his aide Rodriguez and six other Venezuelans. In 2013, the prosecutors began a years-long effort to interview Salazar and others.

In 2015, the U.S. Treasury Department began pressuring Andorra over alleged money laundering. In a report at the time, the Treasury wrote that BPA facilitated laundering of money from Russia, China and Venezuela.

That March, the Andorran government took over BPA.

Oil prices, which had recently exceeded $100 per barrel, that year fell by more than half. Venezuela’s economy foundered.

CAMC pulled its team of 40 employees from the rice site, people involved in the project said. Locals looted scrap abandoned by CAMC. Jobless workers sold leftover cables and lightbulbs, former managers said.

Still, Maduro has sought to make something of the unfinished project.

In February, Agriculture Minister Wilmar Castro inaugurated the “Hugo Chavez” plant, snipping a ribbon in front of rice sacks emblazoned with Venezuelan and Chinese flags. No one from CAMC attended, according to a person present at the ceremony.

Instead of machinery able to process 18 tonnes each hour, workers are packing imported rice by hand. “There’s not a gram of rice growing anywhere here,” said Mariano Montilla, a 47-year-old local who lives off the few crops he can coax from nearby scrubland.

“It seemed like a revolutionary idea,” he said of Chavez’s initial promise. “Now we’re starving.”

Source: Reuters