Image copyright PRESS INFORMATION BUREAU

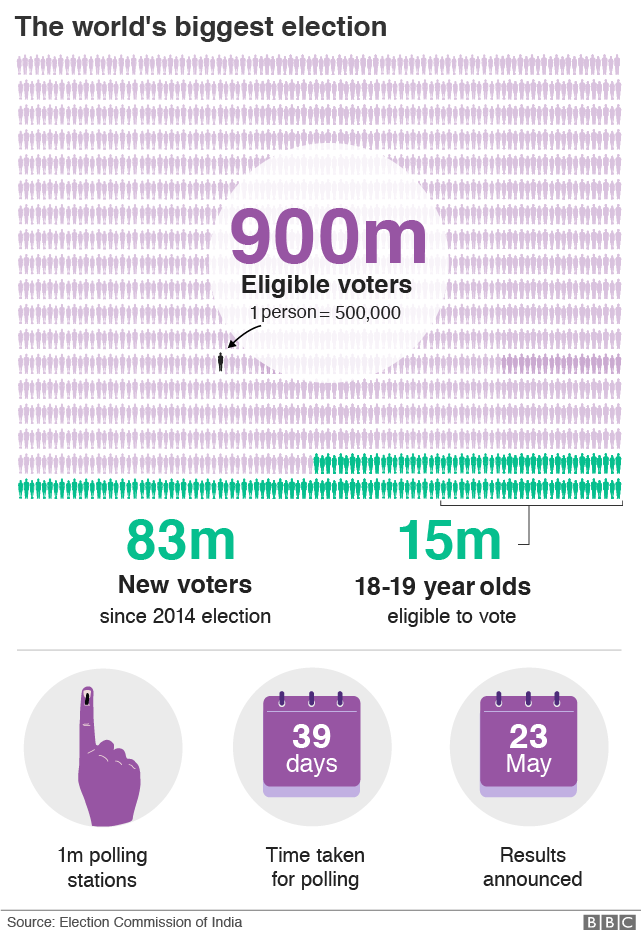

Image copyright PRESS INFORMATION BUREAUThe armies of the world’s two most populous nations are locked in a tense face-off high in the Himalayas, which has the potential to escalate as they seek to further their strategic goals.

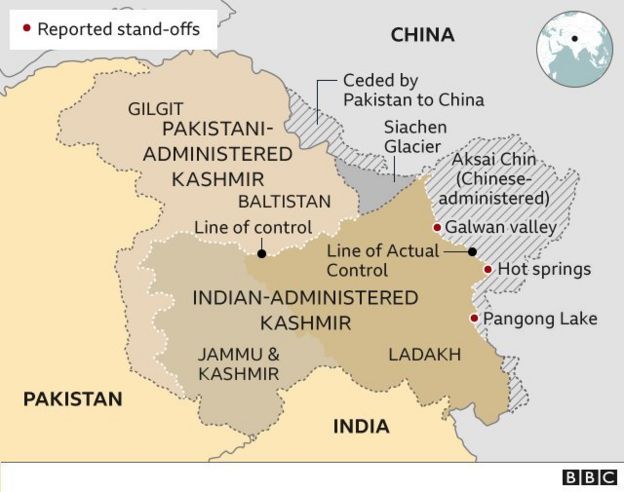

Officials quoted by the Indian media say thousands of Chinese troops have forced their way into the Galwan valley in Ladakh, in the disputed Kashmir region.

Indian leaders and military strategists have clearly been left stunned.

The reports say that in early May, Chinese forces put up tents, dug trenches and moved heavy equipment several kilometres inside what had been regarded by India as its territory. The move came after India built a road several hundred kilometres long connecting to a high-altitude forward air base which it reactivated in 2008.

The message from China appears clear to observers in Delhi – this is not a routine incursion.

“The situation is serious. The Chinese have come into territory which they themselves accepted as part of India. It has completely changed the status quo,” says Ajai Shukla, an Indian military expert who served as a colonel in the army.

China takes a different view, saying it’s India which has changed facts on the ground.

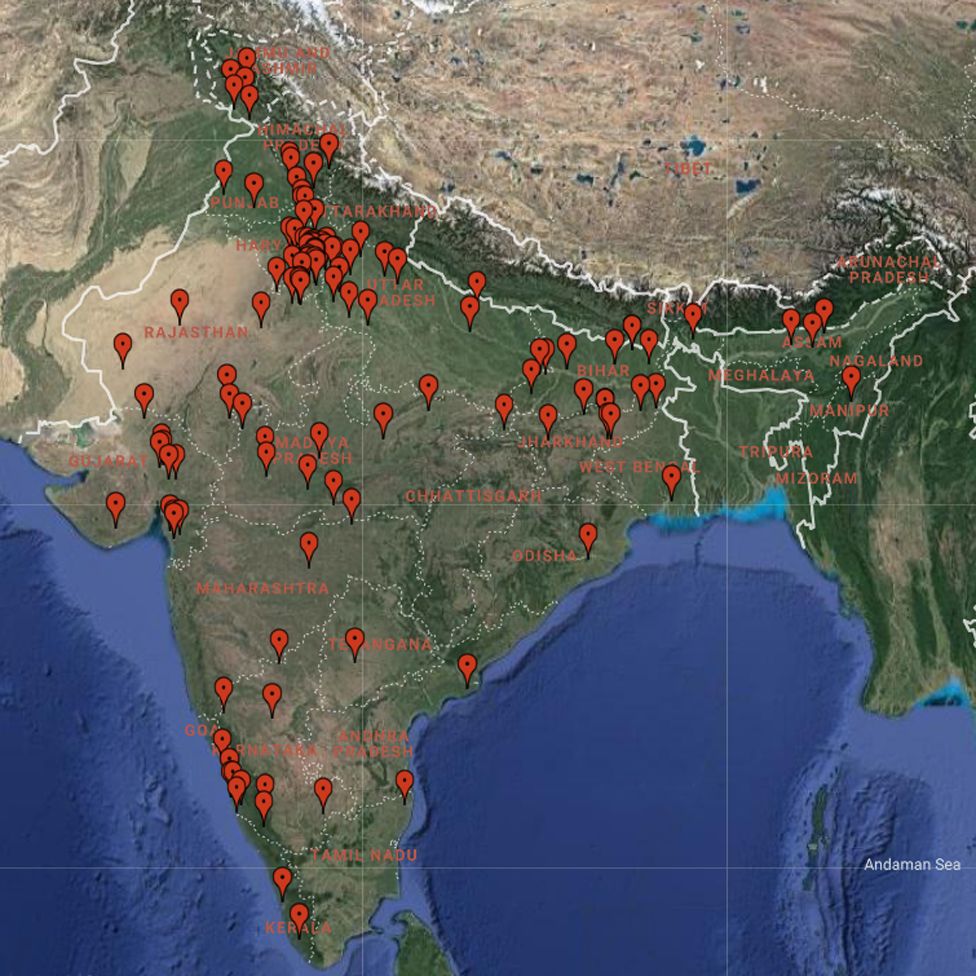

Reports in the Indian media said soldiers from the two sides clashed on at least two occasions in Ladakh. Stand-offs are reported in at least three locations: the Galwan valley; Hot Springs; and Pangong lake to the south.

India and China share a border more than 3,440km (2,100 miles) long and have overlapping territorial claims. Their border patrols often bump into each other, resulting in occasional scuffles but both sides insist no bullet has been fired in four decades.

Their armies – two of the world’s largest – come face to face at many points. The poorly demarcated Line of Actual Control (LAC) separates the two sides. Rivers, lakes and snowcaps mean the line separating soldiers can shift and they often come close to confrontation.

The current military tension is not limited to Ladakh. Soldiers from the two sides are also eyeball-to-eyeball in Naku La, on the border between China and the north-eastern Indian state of Sikkim. Earlier this month they reportedly came to blows.

And there’s a row over a new map put out by Nepal, too, which accuses India of encroaching on its territory by building a road connecting with China.

Why are tensions rising now?

There are several reasons – but competing strategic goals lie at the root, and both sides blame each other.

“The traditionally peaceful Galwan River has now become a hotspot because it is where the LAC is closest to the new road India has built along the Shyok River to Daulet Beg Oldi (DBO) – the most remote and vulnerable area along the LAC in Ladakh,” Mr Shukla says.

India’s decision to ramp up infrastructure seems to have infuriated Beijing.

Image copyright AFP

Image copyright AFPChinese state-run media outlet Global Times said categorically: “The Galwan Valley region is Chinese territory, and the local border control situation was very clear.”

“According to the Chinese military, India is the one which has forced its way into the Galwan valley. So, India is changing the status quo along the LAC – that has angered the Chinese,” says Dr Long Xingchun, president of the Chengdu Institute of World Affairs (CIWA), a think tank.

Michael Kugelman, deputy director of the Asia programme at the Wilson Center, another think tank, says this face-off is not routine. He adds China’s “massive deployment of soldiers is a show of strength”.

The road could boost Delhi’s capability to move men and material rapidly in case of a conflict.

Differences have been growing in the past year over other areas of policy too.

When India controversially decided to end Jammu and Kashmir’s limited autonomy in August last year, it also redrew the region’s map.

The new federally-administered Ladakh included Aksai Chin, an area India claims but China controls.

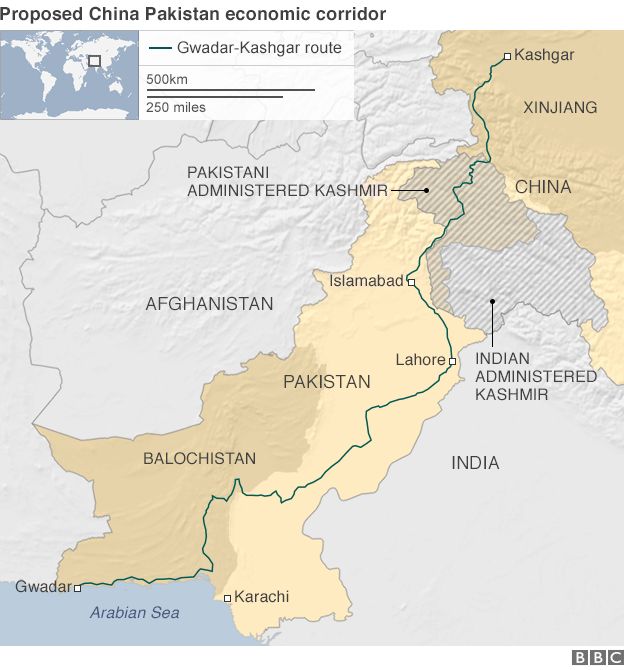

Senior leaders of India’s Hindu-nationalist BJP government have also been talking about recapturing Pakistan-administered Kashmir. A strategic road, the Karakoram highway, passes through this area that connects China with its long-term ally Pakistan. Beijing has invested about $60bn (£48bn) in Pakistan’s infrastructure – the so-called China Pakistan Economic corridor (CPEC) – as part of its Belt and Road Initiative and the highway is key to transporting goods to and from the southern Pakistani port of Gwadar. The port gives China a foothold in the Arabian Sea.

How dangerous could this get?

“We routinely see both armies crossing the LAC – it’s fairly common and such incidents are resolved at the local military level. But this time, the build-up is the largest we have ever seen,” says former Indian diplomat P Stobdan, an expert in Ladakh and India-China affairs.

“The stand-off is happening at some strategic areas that are important for India. If Pangong lake is taken, Ladakh can’t be defended. If the Chinese military is allowed to settle in the strategic valley of Shyok, then the Nubra valley and even Siachen can be reached.”

- New images show Doklam plateau build-up

- The forgotten victims of the world’s highest war

- What was behind the China-India border row?

- Bhutan’s ‘Shangri-La’ caught between rivals

In what seems to be an intelligence failure, India seems to have been caught off guard again. According to Indian media accounts, the country’s soldiers were outnumbered and surrounded when China swiftly diverted men and machines from a military exercise to the border region.

This triggered alarm in Delhi – and India has limited room for manoeuvre. It can either seek to persuade Beijing to withdraw its troops through dialogue or try to remove them by force. Neither is an easy option.

“China is the world’s second-largest military power. Technologically it’s superior to India. Infrastructure on the other side is very advanced. Financially, China can divert its resources to achieve its military goals, whereas the Indian economy has been struggling in recent years, and the coronavirus crisis has worsened the situation,” says Ajai Shukla.

What next?

History holds difficult lessons for India. It suffered a humiliating defeat during the 1962 border conflict with China. India says China occupies 38,000km of its territory. Several rounds of talks in the last three decades have failed to resolve the boundary issues.

China already controls the Aksai Chin area further east of Ladakh and this region, claimed by India, is strategically important for Beijing as it connect its Xinjiang province with western Tibet.

Image copyright GETTY IMAGES

Image copyright GETTY IMAGESIn 2017 India and China were engaged in a similar stand-off lasting more than two months in Doklam plateau, a tri-junction between India, China and Bhutan.

India objected to China building a road in a region claimed by Bhutan. The Chinese stood firm. Within six months, Indian media reported that Beijing had built a permanent all-weather military complex there.

This time, too, talks are seen as the only way forward – both countries have so much to lose in a military conflict.

“China has no intention to escalate tensions and I think India also doesn’t want a conflict. But the situation depends on both sides. The Indian government should not be guided by the nationalistic media comments,” says Dr Long Xingchun of the CIWA in Chengdu. “Both countries have the ability to solve the dispute through high-level talks.”

Chinese media have given hardly any coverage to the border issue, which is being interpreted as a possible signal that a route to talks will be sought.

Pratyush Rao, associate director for South Asia at Control Risks consultancy, says both sides have “a clear interest in prioritising their economic recovery” and avoiding military escalation.

“It is important to recognise that both sides have a creditable record of maintaining relative peace and stability along their disputed border.”

Source: The BBC